Population chatter for clearer and broader thinking about fertility

Research Article

Jenny Trinitapoli1* and Gertrude Finyiza2

1Department of Sociology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, USA 2University of Denver, Denver, USA *Corresponding author: Jenny Trinitapoli, jennytrini@uchicago.eduThis paper examines reproductive vulnerability in Balaka, Malawi by prioritizing population chatter – how ordinary people perceive, narrate, and debate the fertility, mortality, and migration conditions around them. The authors, a cultural anthropologist and a demographer, discuss the translation of the concept of vulnerability in Malawi, identify the common metaphors and predicaments used to express it, and identify articulations of vulnerability in everyday conversation that show how young adults perceive and cope with vulnerabilities during an especially eventful stage of life. Drawing upon 600 pages of ethnographic fieldnotes written in 2015, the analysis is organized around the following question: What we would know about sexual and reproductive health if we privileged ordinary women’s exchanges with one another in everyday conversation over the entrenched measures (i.e., ideal family size, desired time to next birth, unmet need, contraceptive discontinuation rates) that have come to define sample surveys? Results are organized around three key themes: 1) the moral nature of population chatter; 2) widespread discontent with the predominant contraceptive method; and 3) food insecurity as a vulnerability that has relevance for contraceptive behaviors.

Introduction

Interested in both the social science discourse on reproductive vulnerability and the resonance (or lack thereof) of discourse with the realities of daily life, our essay takes an unorthodox approach. Assuming the “naïve observer” approach Susan Watkins (1993) suggested in her iconic paper about women in demography, we highlight the limits of some concepts that dominate the academic literature and suggest some new avenues of inquiry based on the themes that dominate everyday conversation in ordinary people’s lives. Influenced by the life-course approach to vulnerabilities (Kreager 2006, Schröder-Butterfill & Marianti 2006, Spini et al. 2017), we focus on young adulthood because this is the time of life during which time union formation, pregnancies, and births are densely distributed. This invitation to think about reproductive vulnerability in the context of Malawi sent us, a cultural anthropologist and a demographer, inquiring in two directions. Given that the term can be vague and difficult to define in English, how does the concept of vulnerability work ‘in translation’? What does everyday conversation reveal about the things young adults in Malawi feel vulnerable to and their strategies for coping during this especially eventful period of the life course?

Our setting is Balaka Boma, 2009-2019. The boma is a trading town and district headquarters in Malawi’s southern region. This densely populated community of 40,000 residents is surrounded by hundreds of smaller, rural villages. Most families survive on a combination of subsistence agriculture and petty trade, and although the area is diverse in terms of religion, ethnicity, language, lineage patterns, and livelihood strategies, they are held together under a single traditional authority (TA Nsamala) and the shared infrastructure (market, hospital, bus depot, commercial farms, etc.) of the boma. In 2010 the median age at first marriage for women in Balaka was 18, median age at first birth was 19, and adult HIV prevalence for the region stood at about 13 percent.

Translation and Aphorism

We begin with the matter of translation. The most common translation for vulnerability in Chichewa, Malawi’s most widely spoken language, is kukhala pa chiopsyezo: ‘to be unprotected’ or ‘to be insecure’. The phrase kuthekera kofooka, ‘the possibility of becoming weak’, is also close. In Chiyao, widely spoken in Balaka, the phrase is kulaga mu chitetzo or ‘lacking protection’. In both languages, the terms denote the risk of death and suggest an economic situation – the threats of starvation, injury, and illness. To a lesser extent the terms connote ‘suffering’ understood sometimes in emotional terms and other times as hunger – lacking basic necessities that mark one as abjectly poor. In both languages, the translations carry a sexual undertone; much like a condom, a lack of protection leaves one susceptible to pregnancy and to STIs, including HIV.

To the extent that language is indicative of ‘how we perceive, how we think, and what we do’ (Lakoff & Johnson 2003 [1980], p. 124), it is worth noting that the Chichewa and Chiyao languages are full of conversational aphorisms that index vulnerabilities and that contraception and pregnancy are often the objects to which this kind of talk is applied. We cataloged dozens of relevant aphorisms and discuss just a few here to show the kinds of predicaments they capture. The first type treats vulnerability as illness, injury, or the risk of it: kuwonjezera pakhungo loyera means ‘adding a wound to clean skin,’ and the specific detail of clean skin suggests a state transition from health to illness. Another popular metaphor considers the risk of injury (and death) ‘like a child in a thunderstorm’ (mwana nyenje). The analogy of ‘living in pain’ (kukhalira pa ululu) likewise circulates widely, often with the addendum of suffering as endurance (i.e., extended periods of time); this can be the physical pain of swollen limbs or chronic gastritis or emotional suffering (for example, at the hands of a cruel or complicated partner). Yet another bundle of aphorisms points directly to the family sphere, and these contain a pointed contradiction. On one side, they emphasize the essential support of family (specifically husbands) as in: mzimu wa mkazi wosowa maziko (‘the spirit of a woman without support’), meaning that a woman without a husband will live in want. On the other side, common aphorisms about marriage valorize perseverance in suffering: banja mkupilira, ‘family is enduring’, with the hardship unstated but strongly implied (Wilson 2013).

Most Malawian aphorisms treat the vulnerable situation as inevitable – marriage, thunderstorm, illness. These vulnerabilities are endemic to having a body and sexual and social relationships. A distinct metaphor of vulnerability emphasizes situations of risk one opts into. The Chiyao phrase kugwira ng’ona m’madzi, ‘attempting to catch a crocodile in water’, implies a task that is risky but not imperative. This difference in characterizations of vulnerability mirrors David Parkin’s (1986) distinction between ‘raw’ and ‘respectful’ fear, where respectful fear is characterized by a predictable cascade of consequences, while raw fear anticipates victimization unrelated to any wrongdoing – an elemental force. Attention to everyday language is instructive: rather than conceptualizing vulnerability as a trait of a subpopulation, as a temporary condition, or as a risk that one assumes, the dominant expressions of vulnerability in Balaka invoke raw fear – a continuous state bound up in relations that can only sometimes be mitigated.

Population Chatter

A central concept for our analysis is population chatter—ongoing conversations with socially salient others about demographic phenomena, including but not limited to contraception, pregnancy, and childbearing (Trinitapoli 2021). In these conversations, people weigh evidence, narrate trade-offs between acceptable and unacceptable risks, and decide how to build and care for their families. Listening to and analyzing population chatter helps researchers understand how people organize facts through cognitive and moral frameworks, drawing conclusions that may or may not align with academic demography. And it is productive for understanding reproductive vulnerabilities because it highlights ordinary social interaction, exposes power relations, and situates population dynamics within a broader social environment.

We leverage the term chatter in direct contrast to the English-language colloquial expression ‘idle chatter’, which connotes casual or meaningless conversation in which nothing much is at stake. Moreover, we deem the keen ear for population chatter an essential tool for developing clearer and broader thinking about fertility and reproduction (Davis 1987, p. 834). This position is entirely consistent with the longstanding habits of anthropological demography (Bledsoe 2002, Gribaldo et al. 2009) and with an important insight from the Theory of Conjunctural Action: that conversations with friends matter for demographic behavior so they should also matter to scholars (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2011, Rutenberg & Watkins 1997).

Population chatter from Balaka reveals that some concepts central to fertility research in low-income settings are entirely absent from everyday conversation. Moreover, dissatisfaction with contraception is widespread, making contracepting itself a vulnerability with consequences for relationships and livelihoods. It intersects with food insecurity and nutrition, long overlooked in sexual and reproductive health scholarship. More than cost, knowledge, autonomy, distance, or cultural barriers, contraceptive side-effects are the primary reason for non-use, yet there is little evidence of serious efforts to treat or reduce them. Third, population chatter is central to how people cope with vulnerabilities – it is a major, substantive, adaptive phenomenon that merits scholarly attention. Too often dismissed as ‘mere’ chatter or problematized as ‘misinformation’, it is integral to how women navigate conflicts involving their bodies, livelihoods, sexual norms, and local clinics.

Data and Methods

Data Sources

We leverage two data sources: longitudinal survey data collected by the Tsogolo La Thanzi (TLT) research team between 2009-2019 and ethnographic data from fieldnotes written in 2015 by Gertrude Finyiza – both fielded in Balaka, Malawi. TLT began in 2009 with a population-representative sample of 1,505 women and 574 men between the ages of 15 and 25 living in or around Balaka’s main market. The first phase (TLT-1, 2009-11) included a series of eight interviews, spaced four months apart. Seventy-eight percent of respondents were re-interviewed in the second phase of TLT (TLT-2, 2015), when respondents were between ages 21 and 31. In a third phase of the study (TLT-3, 2019) sixty-eight percent of the original sample were re-interviewed, at which time respondents had reached ages 25-35. Detailed information about sampling and research design can be found in Yeatman et al. (2019).

While the TLT survey represents the view of academic demography, Gertrude’s fieldnotes are our key source of population chatter. As a research assistant hired to conduct study-focused ethnography alongside an ongoing longitudinal study, Gertrude’s charge was specific but open: to document the everyday conversations about relationships, marriage, family, contraception, and fertility in a changing policy landscape.

Gertrude’s interlocutors are varied. She spends time with friends who run a hair salon and chats with their customers. Together they visit clients’ homes where the styling work unfolds over many hours, with other conversation partners circulating in and out of the scene. She writes about her neighbors – two sisters about her age and a couple in their late forties who co-reside with young-adult children – and accompanies them in their daily chores. At the market, Gertrude unobtrusively hangs out with sellers while they move their goods. Between March and September 2015, Gertrude wrote 4-8 pages at the end of every day and shared her fieldnotes in weekly batches of 20-40 pages.

This corpus of fieldnotes features prominently in a monograph about uncertainty during young adulthood (Trinitapoli 2023). To address the present topic of reproductive vulnerability, we re-read these fieldnotes and analyzed them, assuming the role of naïve researcher à la Watkins (1993): if all we knew about fertility in Balaka was what we understood from Gertrude’s fieldnotes, what would we know? What vulnerabilities do ordinary people articulate in everyday conversation? Which structures and institutions are they interacting with while managing these vulnerabilities? And what does this view of reproductive vulnerability suggest for future research? We refer to Gertrude’s interlocutors using pseudonyms.

Analytic Plan: Consensus, Debates, and Silences

Returning to the original definition of population chatter, what immediately stands out are the things that people discuss explicitly, through narration or debate. Sometimes people share their own fertility trajectories or describe the experiences of a friend to shed light on another person’s hardship. Other times, population chatter takes the form of criticism. This includes observations about others they may point out as attention-worthy to a friend or conversation-partner, even if the basic idea is settled.

There are also distinct varieties of silence for a reader to notice – first, that which people do not discuss because it is so obvious and taken-for-granted it need not be mentioned. Second, that which is undiscussed because it lies far outside the capacity of one’s imagination (we offer the example of assisted reproductive technologies, which are debated among friend-groups in rich countries but would never be mentioned in Malawi). Our approach to silences follows Walters’s (2021) concept of microsilences, which emphasizes that ‘historical demographic data sources are embedded in hegemonic relations which render their categories, constituencies, and contexts selective’ (p. 2) and argues that these silences can be ‘questioned and compensated on the basis of the qualitative record’ (p. 3). Although Walters was writing about the difficulty of historical demography in Africa due to a lack of quality sources, her concept of microsilences applies to contemporary settings. Since the concepts that dominate everyday conversation differ markedly from the staple measures fertility scholars developed decades ago, we shift the analytic lens and ask anew about how micro-level utterances (and silences) help us better understand the macro-level phenomena scholars seek to apprehend.

Results

Setting the Stage: Three Qualities of Population Chatter from Balaka

Before turning to the four key fertility-related themes that emerge from 600 pages of fieldnotes, we frame these results by emphasizing three qualities of this corpus and their relationship to knowledge produced by representative sample surveys conducted in this part of the world.

First, the population chatter in Balaka is voluminous. In fact, the volume of population chatter itself is mentioned by several of Gertrude’s interlocutors. In the context of a conversation at the market with an agemate who works for an NGO, for example:

I asked Sophie if young girls use family planning methods. She said: “Some do while other they don’t.” I asked, “How do you know?” She said she always hears them talking about pills and injections during break time.

Sophie’s remark underscores the repetitiveness of this topic in everyday conversation; her colleagues talk about contraception to the point of becoming tiresome.

Second, while analysts worry about social desirability bias when interpreting survey responses about sexual behavior, the population chatter in Balaka is unsanctimonious, even among women who are only beginning to know one another. In conversation with Grace, a woman Gertrude has met just once before while looking for a house to rent, Gertrude asks where she can access family planning services. The response she receives is one-third informational, one-third biographical, and one-third evaluative:

Grace said you can get it at the hospital for free. But you can also get it at a private hospital. “Just after I divorced my husband, I found out I was pregnant and went to a private clinic. I paid 5000 for abortion and they gave me 2 tablets, and those tablets worked. From there I started getting injections so that I should not be pregnant quickly”.

I asked, “Where do you go to get the injectables?” She said, “When I have money I go to a private clinic, and if I don’t have money I go to a government hospital. They all provide different kinds of family planning methods like depo, pills, condoms, implant. But you know, Gertrude, a lot of men don’t like using condoms. They can use it the first time you have sex together, but after that they ignore condoms”. I asked why, and she explained that the boys say they don’t enjoy condoms when having sex.

This exchange reflects points of consensus about how clinics operate, which contraceptive methods are prevalent, and a widespread preference for private over public clinics. While survey research suggests young women underreport abortions and overreport condom use, it is noteworthy that Grace mentions her abortion unprompted. In this light, population chatter illuminates phenomena that surveys tend to miss. Grace’s response to an inquiry about where to find family planning (FP) services suggests that abortion disclosure between friends may be more common than it is to researchers (Giorgio et al. 2021, Owolabi et al. 2023, Yeatman & Trinitapoli 2011). Likewise, her comment on condoms echoes a growing body of work emphasizing pleasure as an unprioritized dimension of reproductive health (Higgins & Hirsch 2007, 2008, John et al. 2015, Tavory & Swidler 2009). Note how closely Grace’s appraisal of condom use in new relationships fits the Yao phrase for vulnerability: kulaga mu chitetezo, lacking protection. Note also the name of Malawi’s country’s most popular condom brand Chishango – ‘shield’ in Chichewa. Following decades of public-health campaigns to prevent HIV transmission, the concept of vulnerability has become practically inseparable from coitus.

A third point from our corpus is that population chatter is evaluative. Women observe one another closely, and their critiques reveal local norms around ‘correct’ child spacing. In one example, Balaka residents gossip about a friend who had children too close together; in another, they criticize an acquaintance’s unpregnant state.

During a quiet day at the hair salon, Gertrude chats with two employees, who are watching a film to pass the time.

Gift turned to Promise and asked, “Why is it that your friend is pregnant again?” (Gift was referring to the pregnant girl who came to help Promise braid my hair a week ago.) Promise answered, “She was using family planning methods [pills] after giving birth to the first child, and she was just taking it the same day that the man came to spend a night with her. But that didn’t work, and she found herself pregnant again. She is not married; that man just comes and goes. Gift said, “You mean that man just comes to give her children, and then leaves?” (We laughed). I asked, how old is she? And Promise told me that she is twenty-three.

In an analogous exchange, the three women make fun of Gift, who is not pregnant:

Why is it that you’ve not been pregnant since we’ve met you? It’s been two years with your husband. Where does he even sleep? Does he stay on the veranda?

Overall, the population chatter in Balaka is voluminous, unsanctimonious, and evaluative.

Population Chatter alongside Staple Demographic Measures

Ideal family size (IFS) is among academic demography’s staple measures; it anchors thousands of studies about fertility transitions, contraception demand, and social norms. IFS is a global measure sometimes used to proxy future completed family size (Coombs 1974), so it is noteworthy that the population chatter in Balaka contains no such statements. Over months of everyday conversations with women from their teens to late forties, Gertrude never spoke with an interlocutor who made a declaration about the number of children they hoped to have in their lifetime.

What does this mean for fertility research in Balaka or similar settings? The absence of IFS statements need not imply that fertility lies outside the calculus of conscious choice. Discussions about childbearing plans are common, though they diverge from Coale’s (1973) vocabulary of advantages and disadvantages. Grace’s comment above illustrates: she takes injections to avoid becoming ‘pregnant quickly’. In line with international efforts to promote child-spacing, everyday statements about the desirability of pregnancy tend to stress timing, anchored to the youngest child’s age.

Timing is also linked to relationships, particularly when a woman wants a child with a specific man but needs time to assess his suitability as a provider, partner, and father. Take, for example, this exchange with a friend Gertude had not seen for several weeks. When Gertrude asked after her husband she replied:

Gertrude, I am still married. My husband is well. Today he has gone to Mbera to find the bike mechanic; he hasn’t been able to go far because his bike doesn’t work properly. You know, my husband doesn’t go to his ex-wife, and he takes good care of the children he has with her. Now he wants me to have his child, and I am thinking about it, but I’m not ready.

The key phrases about fertility women in Balaka use in their daily conversation tend to be made with respect to their pregnancy desires: ‘soon’ (within approximately two years) versus ’not ready’ (everything else) and partner-specific desires: ‘with him’ versus ‘not with him’.

This absence of IFS-style statements need not imply the kind of collective innumeracy about fertility van de Walle (1992) observed during the 1980s, when up to 50% of women in population-based surveys fielded in Africa were responding to questions about ideal family size with answers like ‘don’t know’ or ‘up to God’. Here again, the comparison between population chatter and survey data is instructive: when asked about numeric ideals, TLT respondents answered readily and non-numeric responses were negligible, with only two or three failing to provide a number.

Young adults in Balaka are numerate about fertility in the sense that, when asked about fertility in the context of a survey, they know the drill and recognize the expectation for a numeric answer. Nonetheless, population chatter suggests that ideal family size holds little relevance for everyday life. We characterize this reality as a semi-numerate fertility regime: questions about IFS are answered numerically, and even unstable IFS statements carry some predictive power, despite the fact that completed parity at age 49 is rarely articulated. This also suggests that concepts other than IFS may be more salient for understanding fertility decisions in Balaka. Relying on population chatter to shed new light, we see that many that of the salient organizing concepts relate to vulnerabilities.

Contraception: Prevalence, Access, and Method Type

Family planning is key among Malawi’s ongoing efforts to improve population health. According to the Malawi FP Summary Report from 2022:

Malawi committed to an ambitious overall goal of increasing its modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) for all women from the baseline of 38 percent in 2012 to 60 percent by 2020 with a focus on reaching the 15–24-years of age group. To achieve what was pledged, the Government of Malawi defined clear objectives under three main pillars to execute the FP2020 agenda: policy, service delivery, and financing. These commitments were renewed in 2017 to take stock of progress made and to update the final set of activities that would enable Malawi to reach its FP2020 goal (Health Policy Plus and Ministry of Health Malawi 2022, p. 5).

Malawi FP2020 program has been transformative for women’s health. Writing in 2022, the Global Burden of Disease team on contraceptive mixing estimated that the mCPR increased at least 30 percentage points since 1970 (Haakenstad et al. 2022). Estimates from the Demographic and Health Surveys tell a similar story, with the mCPR for all women rising from 6% in 1992 to 45% in 2015 (MDHS, 2016) to 60% in 2024 (MDHS, 2024). The rise in mCPR was achieved through increases in injectables (by far the leading method), followed by implants (second in popularity).

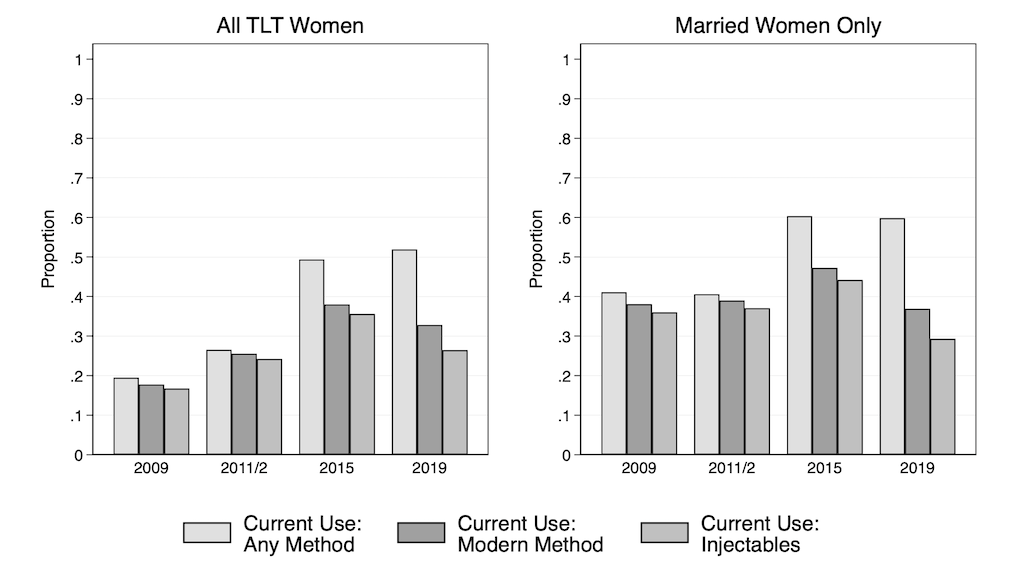

Unlike the DHS, which covers the entire reproductive age range in repeated cross-sections, TLT follows the same women over time. The cross-sectional surveys demonstrate that among young women aged 15-24 – a strategically important group – prevalence rose from a mere 3% in 1992 to over 30% in 2015, and these changes are nothing short of transformative. Figure 1 depicts contraceptive prevalence from a different view, separately for all women enrolled in the TLT study and for married women only. Estimates for 2009 represent prevalence for women aged 15-25 and estimates in 2019 for women 25-35.

Figure 1: Self-reported contraceptive use - proportion in the TLT sample. Source: TLT-1, TLT-2, TLT-3

TLT estimates of current use of any method (including traditional methods) and modern methods align closely with DHS estimates for the corresponding age-groups (MDHS 2016). With respect to method mix, options in Balaka are limited, and the TLT data show that injectables were virtually synonymous with modern methods from 2009 to 2015, but by 2019, access to oral contraceptive pills and implants had expanded. Reflecting these trends, much of the population chatter in Balaka centers on injectable contraception, commonly referred to as ‘depo’. Consistent with the insights from national estimates, depo use in Balaka grew from 24% (among women 18-28) in 2011 to 38% (among women 21-31) in 2015. But despite massive investments from the national family planning program and the international community, the prevalence of modern contraceptives fell in 2019, returning to 2011 levels of about 26%. What explanations does the population chatter give for this decline in current use between 2015 and 2019?

To answer this question, we amplify the loudest chorus from Gertrude’s fieldnotes – conversations about contraception. Population chatter from Balaka reiterates themes from the scientific literature, including the need for ‘discreet’ methods that can be concealed from mothers, husbands, and others. Nulliparous women fear that hormonal contraception use may cause infertility, and the population chatter suggests that nurses share this view, denying hormonal contraception to women who have never given birth. The very idea of infertility is a vulnerability that shapes clinical practice; women articulate this fear and discuss in everyday conversation their strategies for navigating the associated obstacles. In this exchange, one woman tells Gertrude how to present herself at the government clinic:

If you go to the government hospital, they will always ask if you have children or not. And if you say you don’t have any children, they will not provide it to you. The daughter of my neighbor wanted to get injections, but the nurses refused to give it to her because she doesn’t have any child. So the girl went back a week later, saw a different nurse and cheated, saying that she has a child and doesn’t want to fall pregnant again because she wants to continue her education. So that nurse gave it to her. If you can afford a private clinic, they will give it to you, but if you go to the government clinic, remember to cheat them about your marital status. Say you have children already.

Information about family planning - where to go, when to show up, and expected costs, flows freely through Gertrude’s conversational networks. This highlights another microsilence: while fees are discussed, population chatter never frames the costs as prohibitive. Many clinics offer free or subsidized services. Travel to the clinic is described as ‘tiresome’, but never as a barrier to access. With the right pretense, contraception is ‘not difficult’ obtain.

The single loudest theme from Gertrude’s fieldnotes is how much people hate the side effects they attribute to contraception. Young women, older women, and men alike all complain about side effects and complications. While the policy reports and the TLT survey data represent the perspective of academic demography, relying on staple measures such as the modern contraceptive prevalence rate and contraceptive method mix, the population chatter shifts our attention to the vulnerabilities associated with contraception.

Contraceptive Side Effects and Narratives of Discontinuation

Absent evidence of new obstacles to access, injectable use may decline in a population for purely mechanical reasons if the proportion of women in union falls or desired fertility rises. The TLT data allow us to test this by tracking trends in marital status and the proportion wanting a/nother child soon (i.e., within the next two years). Shown in Table 1, we find no difference in the proportion of women who want a baby soon or the proportion of women in union between 2015 and 2019. Unable to link declining depo use to fertility desires or family formation, we turn to two sources for insight: scholarly literature on contraceptive discontinuation and Balaka’s population chatter.

|

Year |

Current Depo Use (%) |

Wants a Child Within 2 Years (%) |

In Union (%) |

|

2009 |

17 |

14 |

76 |

|

2011 |

24 |

13 |

84 |

|

2015 |

36 |

18 |

91 |

|

2019 |

26 |

20 |

91 |

Table 1: Aggregate view of women's contraceptive use, fertility desires, and union status in Balaka, Malawi. Source: TLT-1, TLT-2, TLT-3

High-quality studies of contraceptive discontinuation name method-related reasons and health-effects as the number-one cause of discontinuation globally; injectable users are the most likely to stop for this reason, and switching remains low in sub-Saharan Africa. Stated differently: when people discontinue use of a certain method of contraception because of health concerns, more than 80% in Morocco, Moldova, Vietnam, and Turkey choose a different method. However, in Malawi, only 14% of women switch methods. Low probabilities of switching (between 20-30 percent) characterize other contexts, but Malawi has the distinction of the lowest documented switching rate in any country that fields a DHS (Ali et al. 2012).

Population chatter helps explain Malawi’s exceptional discontinuation rates: Gertrude’s fieldnotes contain over 50 accounts of women complaining about depo. For some, side effects are inconvenient but not severe enough to prompt a method change. For Agnes, heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is a laughable inconvenience rather than a deep concern.

When we reached town we went to the post office first where Agnes cashed 5000mk; she said her boyfriend who stays in Blantyre sent it to her. From there she asked us to escort her at BLM clinic to get depo. She said she likes getting depo so that she should not be pregnant but the only problem is that she always menstruates for two to three weeks, and sometimes when she has gone to visit friends she realizes that she is menstruating again.

But for others, side-effects are severe, reflecting profound vulnerability, defined as suffering and weakness – kuthekera kofooka.

For example, consider Monica, age 25, who frequently chats with Gertrude about family matters - from picking up her sister’s antiretroviral medications to her feelings about her father’s recent marriage to her former classmate.

Monica complained that she has been menstruating for a month now because she used depo. Since her husband left for South Africa she decided to stop depo because she is tired of bleeding the whole month. She said she might try other methods when she finds a boyfriend, because she doesn’t know if her husband is abstaining wherever he is. She said she is just lazy to go back to the hospital to explain that she is just menstruating because of the depo. “But if you go to complain they will help by giving you some tablet”.

After a ‘break’ from depo to ease bleeding, Monica returns to the clinic for another injection – her husband is still away, and she is juggling two casual partners but does not want a child with any of these men. Interestingly, Monica understands she could address the side effects but initially describes herself as ‘too lazy’ to pursue solutions. Later, in September, Gertrude records another relevant exchange:

Monica came to sell samosa to my house, and I bought some for 100mk. Monica said she was selling early in the morning so that she can go to the hospital today. I asked if she was sick, and she said that she is very weak because she has been menstruating since July. Last week she went to the hospital to get help. They tried to help her, but nothing changed. I asked what kind of medication they gave her, and she said, “Tablets like the pill”. I asked if she didn’t miss any day taking those pills. “Yeah, I missed some days, because when I take those pills I need to eat a lot, and I didn’t have food at home. So I had to stop taking them for awhile and then continue”.

Monica receives pills to manage side effects (Lethaby et al. 2019, Magalona 2024), but their own side effect, increased appetite, poses a new problem given her food-insecure circumstances. Progestin’s appetite-increasing effects are well documented, as are those of iron supplements, often recommended for heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). However, to our knowledge, family planning protocols do not account for or support a nutritional floor – whether bleeding is related to contraceptives or not.

Monica is not alone in understanding HMB as a consequence of contraception (Alvergne et al. 2017, Magalona 2024). Patience, in her early 30s, was an early adopter of implants after they became available between DHS rounds 2010 and 2015. With two children already and no support from their fathers, another pregnancy with her new boyfriend would be inopportune. Nonetheless, Patience goes to the clinic to have her implant removed, prompting Gertrude to ask about her motivation.

I asked Patience why she took out the implant, and she said she wanted to try other methods of family planning because the implant was making her weak and pale. She said she has not been sleeping with men every day, and the implant was troubling her. Instead she wanted to try the pills or depo. But she didn’t do it at the same time when she took out of the implant because she heard from her friends that when you just take out the implant that means you can stay for some time before getting pregnant.

Patience is knowledgeable about contraception and connected to health care services. Her belief that fecundity returns slowly after implant removal comes from her conversations with friends, not health-care providers. She plans to adopt a new method when she feels ready, so in the discontinuation tables, Patience gets categorized as a stopper rather than a switcher. Population chatter captures many conversations describing the decision to stop using a hormonal method rather than switch, even though the speaker does not want to conceive. Using the categories of academic demography, these women are counted among those experiencing ‘unmet need for modern contraception’, however the population chatter suggests a need to rethink that category (Senderowicz et al. 2023).

Effects of Side-Effects as Vulnerabilities: Relationships, Livelihood Strain, and Food Insecurity

‘Weakness’ and heavy menstrual bleeding are the main complaints in Gertrude’s fieldnotes. Others describe swollen legs, intense headaches, large clots, and amenorrhea – all recognized in the clinical literature and by health care providers in Balaka. In Chichewa, this vocabulary of weakness equates vulnerability. However, population chatter highlights four additional concerns: diminished libido, relationship strain, livelihood strain, and hunger.

Unlike Agnes’s relatively unbothered response to constant menstruation, this man summarized a widespread concern about the effects on romantic relationships.

These injections – they make women menstruate all the time. Then the husband gets tired and will find someone else to have sex with. I asked, “Do you mean that men can’t even wait for their wife to finish menstruation?” He said, “Some wait, but many don’t.”

Views on sex during menstruation differ within Balaka; there is no consensus. However, descriptions of sexless marriage as a negative side-effect of contraception were uncontested – another insight we draw from microsilences. In a context of high HIV prevalence and relationship instability, extramarital sex is considered dangerous. Side effects, therefore, are not purely physiological: prolonged bleeding from injectable contraception also threatens relationship stability. Forgoing romantic relationships altogether is rarely discussed, as it signals another vulnerability – that of ‘a woman without support’.

Loss of sex drive – rarely discussed in demographic literature – is another side effect. While assisting her friend at New Styles salon, Gertrude describes a growing market for libido support, tied to shared understandings of contraceptive side effects.

As I was washing her hair a woman came by to show us some traditional medicine; she was selling the powder at 300mk per packet. She said that this medicine will make the women have sexual feelings. Men have been complaining that when the women use depo it makes them not have sexual feelings, so the medicine will help the women become aroused.

Not all Balaka residents pursue libido support alongside contraception, but through listening to population chatter we hear many women self-medicating to support libido, suppress prolonged menstruation, or boost energy. More research about this ‘mixing’ of medicines for family planning, health, and relationship support is sorely needed.

‘Weakness’ is an ambiguous symptom with many causes, and providers routinely list fatigue among other anticipated side-effects. Yet characterizing side effects as ‘common’ and ‘minor’ downplays the real consequences for livelihood strain. One Balaka woman, dizzy after injections, could not sell at the market, leaving her family hungry for an entire week. Another was too fatigued to fetch water, and since her husband has migrated and her child was too young for the task, their situation became dire. These are not mere inconveniences. Nutrition, contraception, and livelihoods are not yet empirically linked in the scholarly literature, even though they are clearly linked in the minds of Balaka residents.

Beyond prolonged menstruation, women who do not menstruate while contracepting likewise experience vulnerability. Lacking the reassurance of regular menses, some fear that they are pregnant, while others fear for their health and fecundability. Across the world, women of reproductive age track their menstrual cycle and interpret it as a vital sign of general health (Stevens et al. 2023). In a context of endemic disease, these reassurances are especially crucial. Many Balaka residents experiencing amenorrhea stop contracepting to ‘rest’ their bodies, resuming only when menstruation returns, signaling good health and fecundability. This contraceptive pause, absent a desired pregnancy, is best understood as a strategy for coping with vulnerability.

Using TLT survey data, we estimated the size of this subgroup of non-users by linking reasons given for non-use with desired time to next birth (see Table 2). The group is sizable, theoretically important, and their complaints should be heard in both clinical and research settings. Notably, of 1,400 non-user responses across two waves, none named access or cost as barriers. Partners’ objections appeared only a handful of times, and religious prohibitions just twice. By contrast, 12% of non-users who do not want a child in the next two years simply do not like or cannot tolerate the side-effects, which include pain, fatigue, continuous menstruation, HMB, and negative consequences for relationships and livelihoods.

|

|

|

Percent

|

|

|

Reason for Not Using Contraception |

2015 (N=578) |

|

2019 (N=990) |

|

Primary Explanations |

|||

|

Currently pregnant/postpartum |

28 |

5 |

|

|

Desires pregnancy |

24 |

9 |

|

|

Husband living away |

13 |

5 |

|

|

Using condoms |

15 |

2 |

|

|

Undertheorized Rationales |

|||

|

Side effects |

6 |

|

7 |

|

Don't like them |

6 |

|

5 |

|

Didn't think of it |

6 |

3 |

|

|

Miniscule Contributions to Discontinuation |

|||

|

Contraindicated by clinicians |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Don't know how to get them |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Too expensive |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Partner objects |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Morally wrong/religious objection |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Presumed infertility |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Note: columns do not total 100, as more than one reason could be given. |

|||

Table 2: Self-reported reasons for not using contraception by women in union and not using contraception in Balaka, Malawi. Source: TLT-2 (2015), TLT-3 (2019).

Discussion

Population chatter cannot replace high-quality, population-based surveys on sexual and reproductive health and fertility. Standardized surveys remain essential for making cross-national comparisons, tracking trends, and producing sound estimates. Yet everyday conversation about population is generative, because it reveals how vulnerabilities that hardly register in the fertility canon shape decisions about relationships, fertility, and health. The caution is clear: if new research iterates too heavily on the projects and concepts that catalyzed this field decades ago, we risk erasing issues that matter to young adults during peak reproductive years. Whether people are seeking to conceive or to avoid pregnancy, these intersecting vulnerabilities – food insecurity, minor illnesses, and relationship quality – are central, not peripheral, to contraceptive decisions. Given how prevalent and explicit population chatter is on these points, we wonder: why has it taken so long for researchers to hear the message?

Efforts to increase the modern contraceptive prevalence rate in sub-Saharan Africa command billions of dollars and the attention of scores of experts worldwide. Much of the existing literature emphasizes the role of societal and personal barriers to access, especially misconceptions and myths, cultural and religious values (Bahamondes & Peloggia 2019). While researchers acknowledge that injectable contraception is often the only method available in poor communities, we have had little to say about the fact that many women find it intolerable or simply do not like it. In contrast to the clinical studies that categorize side effects as ‘minor’, many women in Balaka describe them as vulnerabilities that affect their relationships, livelihoods, health, and wellbeing. Do we take women’s complaints about contraception seriously enough? Or have researchers been dismissive of the very real challenges associated with managing fertility over a long reproductive career?

What would it look like to make the concerns of everyday life central, rather than peripheral, to new data collection efforts in Balaka? First, rather than spotlighting the categories ‘unmet need’ and ‘premature discontinuation’, we could classify non-use as a legitimate choice (even among women who do not desire another pregnancy in the near future) and emphasize the need for better contraception. Research from high-income contexts shows that levels of contraceptive dissatisfaction and discontinuation are common, even among privately insured women, and that women start and stop methods many times to find methods that work for them (Sittig et al. 2020, Stewart et al. 2025). Women living in low-income contexts likewise deserve access to methods that don’t make them feel sick, dampen libido, or reduce their quality of life. The problems associated with the side-effects reported and discussed here can’t and won’t be solved with more counselling in family planning clinics (Gebrslasie et al. 2023, Modesto et al. 2014).

Second, we would invest serious resources to understand heavy menstrual bleeding as a condition with consequences for women’s livelihoods and wellbeing (Ibrahim & Samwel 2023, Sinharoy et al. 2023). Third, we would initiate new lines of research to understand how women supplement their contraceptive methods to support their overall health. This would include revisiting questions about the extent to which contraceptives alter nutritional requirements, including the basic processes of vitamin and mineral absorption (Bamji 1985, Palmery et al. 2013) and connecting more seriously with the niche field of ethnopharmacology (Moroole et al. 2019, 2020). The answers to these questions would shape larger conversations about the ethics and practicalities of administering massive family planning campaigns in food-insecure contexts like Balaka.

This brings us to a final point about population chatter as a method: this is an especially valuable tool for triangulating local concerns with scientific and policy agendas set by the international community. In addition to their participation in the TLT study between 2009 and 2019, women in Balaka were subject to several projects and programs, including a notorious results-based financing program to improve maternal and child health (Verheijen 2017) and the rollout of a first-generation malaria vaccine. Smaller funded programs included RCT-style efforts to increase cervical cancer screening, improve adherence to anti-retroviral therapy, and promote egg consumption to reduce nutritional stunting. While each of these programs addresses an important issue, the population chatter from Balaka indicates that a major vulnerability is being neglected by the research community. Based on our analysis of population chatter, we are confident that serious studies to address the side-effects women experience from contraception and programs to provide better contraceptive methods at low cost would be welcome in Balaka.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Tsogolo la Thanzi, a research project designed by Jenny Trinitapoli and Sara Yeatman and funded by grants R01-HD058366 and R01-HD077873 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Data files are archived with and available through Data Sharing for Demographic Research. TLT-3 (fielded in 2019) was funded by a Max Planck Society grant awarded to Emily Smith-Greenaway and facilitated by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. This paper benefitted from conversations with scholars at the 9th African Population Conference (Lilongwe, Malawi 2024) and the Fertility Goals PAA Pre-Conference Workshop organized by the Ohio Population Consortium (Washington DC 2025). We are indebted to Philip Kreager, Kaveri Qureshi, and Laura Sochas for editorial guidance and for including us in their seminar about reproductive vulnerability.

Orcid IDs

Jenny Trinitapoli https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2617-8176

Getrude Finyiza https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3874-6884

References

Ali, M. M., Cleland, J. G., Shah, I. H., & World Health Organization (2012) Causes and consequences of contraceptive discontinuation: Evidence from 60 demographic and health surveys. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/75429

Alvergne, A., Stevens, R., & Gurmu, E. (2017) Side effects and the need for secrecy: Characterising discontinuation of modern contraception and its causes in Ethiopia using mixed methods. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine, 2(24), 1–16.

Bahamondes, L., & Peloggia, A. (2019) Modern contraceptives in sub-Saharan African countries. The Lancet Global Health, 7(7), e819–e820. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30199-8

Bamji, M. S. (1985) Oral contraceptives and nutrition interaction. ICMR Bulletin, 15(7), 85–89.

Bledsoe, C. H. (2002) Contingent lives. University of Chicago Press.

Coale, A. J. (1973) The demographic transition reconsidered. In Proceedings of the International Population Conference, Liege (pp. 53–72). International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

Coombs, L. C. (1974) The measurement of family size preferences and subsequent fertility. Demography, 11(4), 587–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060472

Davis, K. (1987) The world’s most expensive survey. Sociological Forum, 2(4), 829–834.

Gebrslasie, K. Z., Berhe, G., Taddese, H., Weldemariam, S., Gebre, G., Amano, A., … & Haile, E. (2023) One-year discontinuation among users of the contraceptive pill and injection in South East Tigray region, Ethiopia. PLOS ONE, 18(5), e0285085. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/authors?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0285085

Giorgio, M., Sully, E., & Chiu, D. W. (2021) An assessment of third‐party reporting of close ties to measure sensitive behaviors: The confidante method to measure abortion incidence in Ethiopia and Uganda. Studies in Family Planning, 52(4), 513–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12180

Gribaldo, A., Judd, M. D., & Kertzer, D. I. (2009) An “imperfect” contraceptive society: Fertility and contraception in Italy. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 551–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00296.x

Haakenstad, A., Angelino, O., Irvine, C.M.S., Bhutta, Z.A., Bienhoff, K., Bintz, C., … & Lozano, R. (2022) Measuring contraceptive method mix, prevalence, and demand satisfied by age and marital status in 204 countries and territories, 1970–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 400(10348), 295–327. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00936-9

Health Policy Plus and Ministry of Health Malawi (2022) Malawi FP2020 Assessment: Summary Report. Palladium, Health Policy Plus. http://www.healthpolicyplus.com/ns/pubs/18671-19157_FPAssessmentSummaryReport.pdf

Higgins, J. A., & Hirsch, J. S. (2007) The pleasure deficit: Revisiting the “sexuality connection” in reproductive health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(4), 240–247. doi: 10.1363/3924007

Higgins, J. A., & Hirsch, J. S. (2008) Pleasure, power, and inequality: Incorporating sexuality into research on contraceptive use. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1803–1813. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2007.115790

Ibrahim, P. M., & Samwel, E. L. (2023) Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and its associated factors among women attending Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre in Northern Eastern, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. The East African Health Research Journal, 7(1), 1–6.

John, N. A., Babalola, S., & Chipeta, E. (2015) Sexual pleasure, partner dynamics and contraceptive use in Malawi. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1363/4109915

Johnson-Hanks, J., Bachrach, C. A., Morgan, S. P., & Kohler, H.-P. (2011) The theory of conjunctural action. In Understanding Family Change and Variation (pp. 1–22). Springer Netherlands.

Kreager, P. (2006) Migration, social structure and old-age support networks: A comparison of three Indonesian communities. Ageing and Society, 26(1), 37–60. doi:10.1017/S0144686X05004411

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003 [1980]) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226470993.001.0001

Lethaby, A., Wise, M. R., Weterings, M. A., Bofill Rodriguez, M., & Brown, J. (2019) Combined hormonal contraceptives for heavy menstrual bleeding. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2(2), CD000154. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000154.pub3

Magalona, C. S. (2024). Contraceptive-induced side effects: The role of experience, management, and information on contraceptive use dynamics in Kenya [Doctoral Dissertation]. Johns Hopkins University.

MDHS (2016) Malawi Demographic and Health Survey. ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

MDHS (2024) Malawi Demographic and Health Survey. ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS. https://cms.nsomalawi.mw/api/download/487/2024-MDHS-KIR--Final.pdf

Modesto, W., Bahamondes, M. V., & Bahamondes, L. (2014) A randomized clinical trial of the effect of intensive versus non-intensive counselling on discontinuation rates due to bleeding disturbances of three long-acting reversible contraceptives. Human Reproduction, 29(7), 1393–1399. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu089

Moroole, M. A., Materechera, S. A., Otang-Mbeng, W., & Aremu, A. O. (2020) African indigenous contraception: A review. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 24(4), 173–184.

Moroole, M. A., Materechera, S. A., Otang-Mbeng, W., & Aremu, O. A. (2019) Medicinal plants used for contraception in South Africa: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 235, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2019.02.002

Owolabi, O. O., Giorgio, M., Leong, E., & Sully, E. (2023) The confidante method to measure abortion: Implementing a standardized comparative analysis approach across seven contexts. Population Health Metrics, 21(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-023-00310-0

Palmery, M., Saraceno, A., Vaiarelli, A., & Carlomagno, G. (2013) Oral contraceptives and changes in nutritional requirements. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 17(13), 1804–1813.

Parkin, D. J. (1986) Toward an apprehension of fear. In D. L. Scrunton (Ed.), Sociophobics: The anthropology of fear (pp. 158–172). Westview Press.

Rutenberg, N., & Watkins, S. C. (1997) The buzz outside the clinics: Conversations and contraception in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Studies in Family Planning, 28(4), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137860

Schröder-Butterfill, E., & Marianti, R. (2006) A framework for understanding old-age vulnerabilities. Ageing and Society, 26(1), 9–35. doi:10.1017/S0144686X05004423

Senderowicz, L., Bullington, B. W., Sawadogo, N., Tumlinson, K., Langer, A., Soura, A., Zabré, P., & Sié, A. (2023) Assessing the suitability of unmet need as a proxy for access to contraception and desire to use it. Studies in Family Planning, 54(1), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12233

Sinharoy, S. S., Chery, L., Patrick, M., Conrad, A., Ramaswamy, A., Stephen, A., … & Caruso, B. A. (2023) Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and associations with physical health and wellbeing in low-income and middle-income countries: A multinational cross-sectional study. The Lancet Global Health, 11(11), e1775–e1784. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00416-3

Sittig, K. R., Weisman, C. S., Lehman, E., & Chuang, C. H. (2020) What women want: Factors impacting contraceptive satisfaction in privately insured women. Women’s Health Issues, 30(2), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2019.11.003

Spini, D., Bernardi, L., & Oris, M. (2017) Toward a life course framework for studying vulnerability. Research in Human Development, 14(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1268892

Stevens, R., Machiyama, K., Mavodza, C. V., & Doyle, A. M. (2023) Misconceptions, misinformation, and misperceptions: A case for removing the “mis-” when discussing contraceptive beliefs. Studies in Family Planning, 54(1), 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12232

Stewart, C., Stevens, R., Kennedy, F., Cecula, P., Rueda Carrasco, E., & Hall, J. (2025) Experiences and impacts of side effects among contraceptive users in the UK: Exploring individual narratives of contraceptive side effects. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 30(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2024.2410841

Tavory, I., & Swidler, A. (2009) Condom semiotics: Meaning and condom use in rural Malawi. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400201

Trinitapoli, J. (2021) Demography beyond the foot. In L. MacKellar & R. Friedman (Eds.) Essays: Covid-19 and the global demographic research agenda (pp. 68–72). Population Council.

Trinitapoli, J. (2023) An epidemic of uncertainty: Navigating HIV and young adulthood in Malawi. University of Chicago Press.

van de Walle, E. (1992) Fertility transition, conscious choice, and numeracy. Demography, 29(4), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061848

Verheijen, J. (2017) The gendered micropolitics of hiding and disclosing: Assessing the spread and stagnation of information on two new EMTCT policies in a Malawian village. Health Policy and Planning, 32(9), 1309–1315. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx08

Walters, S. (2021) African population history: Contributions of moral demography. The Journal of African History, 62(2), 183–200. doi:10.1017/S002185372100044X

Watkins, S. C. (1993) If all we knew about women was what we read in demography, what would we know? Demography, 30(4), 551–577. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061806

Wilson, A. (2013) Folklore, gender, and AIDS in Malawi: No secret under the sun. Palgrave Macmillan.

Yeatman, S., Chilungo, A., Lungu, S., Namadingo, H., & Trinitapoli, J. (2019) Tsogolo la Thanzi: A longitudinal study of young adults living in Malawi’s HIV epidemic. Studies in Family Planning, 50(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12080

Yeatman, S., & Trinitapoli, J. (2011) Best-friend reports: A tool for measuring the prevalence of sensitive behaviors. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1666–1667. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300194

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 2 (2025), Issue 3 CC-BY-NC-ND