Anti-abortion politics and changes in abortion miscarriage and stillbirth across time and social strata in Turkey

Research Article

Selin Köksal 1*, Francesco C. Billari2,3, and Ozan Aksoy4,5

1Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom 2Department of Social and Political Sciences, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy 3Dondena Research Centre on Social Dynamics and Public Policy, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy 4Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom 5Nuffield College, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: Selin Köksal, selin.koksal@lshtm.ac.ukAbortion has been legal without restriction in Turkey since 1983. However, the government’s anti-abortion campaign in 2012 has resulted in significant restrictions on abortion services, particularly in public hospitals. Using six waves of the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS), which was administered every five years from 1993 to 2018 (n=32,990), we investigated the trends in abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth rates among ever-married women. We found that, compared to wave 2008, women in wave 2013 were seven percentage points less likely to report an abortion, while they were three percentage points more likely to report an experience of a miscarriage. This pattern continued largely also in the 2018 wave. This unprecedented decline in abortion was observed across all socioeconomic groups, with the strongest decline among lower educated and poorer women. Moreover, the increase in miscarriages was primarily driven by lower educated women and those outside of the richest wealth quintile. Our findings suggest that the government’s anti-abortion campaign led to reduced access to abortion services, and potential misreporting of abortions as miscarriages by reinforcing stigma towards both abortion seekers and providers. The findings underscore how an anti-abortion political climate can exacerbate existing social inequalities, even when abortion remains legal.

Introduction

Access to safe and legal abortion is a basic human rights issue and an essential part of equitable healthcare. According to Article 16 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (hereafter CEDAW), women should have equal rights in deciding ‘freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights’.[1]

Abortion laws have been considerably liberalized in many countries.[2] But liberalization per se does not ensure full access. Access to abortion is often limited by specific exceptions such as gestational limits (Millar 2022) or the pregnant person’s health (Küng et al. 2018), thus positioning abortion as an exception rather than a routine part of healthcare. As definitions of health and gestational limits are shaped by shifting political and social contexts, they can create uncertainty and confusion for both those seeking abortions and providers (Küng et al. 2018). This framing also ties abortion provision to moral conditions, leading some healthcare professionals to face institutional or normative barriers, or to invoke conscientious objection even where abortion is legal (Autorino et al. 2020, Berro Pizzarossa & Sosa 2021). Therefore, the legality of abortion is neither stable nor a straightforward guarantee of access, reflecting an exceptionalised status shaped by social stigma and political rhetoric.

In this study we present a case, Turkey, where the legal status of abortion has not necessarily ensured access to abortion services in practice in recent years, particularly in public health clinics. Since 1983, abortion has been legal in Turkey without restrictions on motives, up to the 10th week of pregnancy. After three decades, however, the reproductive rights of women were reconsidered in 2012, when the then prime minister and several members of parliament initiated an anti-abortion campaign. The former Prime Minister and reigning President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan kicked off this campaign by a speech in which he stated ‘(…) I consider abortion as murder (… ) There is no difference between killing the child in mother’s womb and killing them after the birth’, at the Fifth International Parliamentarians’ Conference on the Implementation of the ICPD (International Conference on Population and Development).[3] This speech appeared within the context of Erdoğan’s and his government’s new pronatalist turn that happened around 2010, which came as a result of rapid population aging in Turkey and of the conservative nature of Erdoğan’s AKP (Justice and Development Party) (Aksoy & Billari 2018).

The anti-abortion campaign gained momentum over time with the support from other members of the parliament and led to a new draft law in June 2012. The draft included the right to conscientious objection by providers, a pre-abortion consultancy service for women and couples, an increase in the penalty for providers providing for abortion after 10 weeks from one to three years in prison, and the requirement of an approval from the judge to abort in rape cases. The law eventually was not passed, mainly due to the reaction from opposition parties and women’s organizations (Cindoglu & Unal 2017).

While the law did not materialize, journalists reported on the de facto inaccessibility of abortion, particularly in public hospitals.[4] A study based on a telephone survey showed that a vast majority of public hospitals (78 percent) refused to provide induced abortion services unless there was a medical necessity (O’Neil 2017). In addition, in March 2014 the Turkish Foundation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics reported that the code for abortion in the public hospital e-system (Medula) was removed, which prevented doctors and patients from scheduling abortion procedures (MacFarlane et al. 2016).

Scholars have tried to evaluate possible consequences of this de facto ban on abortion in Turkey. Saraç & Koç (2020), for instance, estimate the level of misreporting (by giving socially desirable/acceptable answers) in induced abortion over time. Their estimate is indirect and relies on a probabilistic classification model that is based on the ratio of predicted and reported induced abortions. Saraç & Koç (2020) estimate that misreporting increased from 18% to 53% among all terminated pregnancies between 1993-2013. Misreporting was estimated to be particularly high in lower socioeconomic groups, associated with the social and political stigmatization of induced abortion following the 2012 abortion debates. Yet, in Saraç & Koç’s (2020) study, socioeconomic status may affect both predicted (e.g., factors such as contraceptive use and marital status determine the probability of predicted abortions) and reported (e.g., due to differential social desirability) abortions. Hence, the actual distribution of misreporting or indeed of actual abortions across social strata may be more complex.

Pekkurnaz et al.’s (2021) study predictors of women’s choice of place for abortion, conditional on having aborted a pregnancy using Turkey’s Demographic and Health Survey 2013 wave. They report that socioeconomically disadvantaged, single, and young women were less likely to report having used public versus private services for abortion. Pekkurnaz et al. (2021) interpret these findings as a reflection of the stigmatization of abortion by public authorities. Because their analysis conditions on having received an abortion, however, these results are based on a small and selected subsample.

Our study expands on this literature and contributes on several dimensions. We describe the trends of reported abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth from 1993 to 2018 in Turkey relying on the Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) that is conducted in every five years. Past research on abortion in Turkey looked at misreporting and who gains access to abortion separately. Moreover, due to de facto restrictions on abortion, many women may undergo unsafe abortions or alternative self-termination methods, which may result in or be reported as miscarriage or stillbirth. Medical staff too may register cases as miscarriage, especially after 2012 when the abortion debate intensified. This may further encourage women to report their induced abortions as miscarriages (Lindberg et al. 2020) or not report them at all. By simultaneously analysing trends in reported abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth, and comparing them over time, our results will draw a bigger picture to understand the consequences of Turkey’s abortion politics.

As another important contribution of our study, we analyse changes in abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth over time across different socioeconomic strata, defined particularly by educational attainment and household wealth. Past research has looked at variation across social strata either for a single outcome (e.g. misreporting or abortion place choice) or a single year (e.g. Pekkurnaz et al. (2021) consider only 2013). Our subgroup analyses of time trends for the three outcomes are important to detect the societal vulnerabilities and factors that could reinforce existing social inequalities in access to abortion services and healthcare. These analyses will also reveal more fully the consequences of the politicization and de facto banning of abortion for different social strata.

Over the past decade, an increasing number of countries including the United States, Poland, Hungary, and Brazil have attempted or enacted restrictions on abortion services. While the adverse consequences of such restrictions on a range of outcomes are well-documented, far less attention has been paid to how individuals report and narrate their abortion and reproductive experiences under increasingly restrictive political climates (VandeVusse et al. 2023). By examining the Turkish case, this study offers insights into how abortion restrictions may shape the ways individuals communicate and report their abortion and other reproductive experiences in large-scale surveys.

Background

Abortion in Turkey

Abortion has been legal in Turkey since 1983 under the Population Planning Law No. 2827, which permits termination of pregnancy without restriction as to reason up to the 10th week of gestation. This limit remains relatively restrictive compared to many high-income countries, where abortion is typically permitted up to 12 to 24 weeks. The 10th week can be too early for some individuals to recognize their pregnancy or arrange access to care in time, thereby limiting the practical availability of abortion. This constraint may also help explain why abortion rates in Turkey are significantly lower than the European average (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2023).

The law also allows abortion up to the 20th week in case of life-threatening conditions, fetal anomaly, or pregnancies resulting from a criminal act. For married women, spousal consent is required, and for those under the age of 18, parental consent is mandatory. Undergoing abortion beyond the legal gestational limits is subject to financial penalties and imprisonment for the pregnant person. Self-procured abortions via medical abortion remains legally inaccessible as mifepristone has never been registered in Turkey, and misoprostol has been restricted to hospital use since 2012 (Esengen 2024, MacFarlane et al. 2017).

The year 2012 marks a major turning point in Turkey’s abortion politics when the government attempted to reconsider the legality of abortion through a surge in anti-abortion rhetoric led by the former Prime Minister and reigning President Erdoğan. Although the law was not officially changed, research suggests that fewer than eight percent of public hospitals offer abortion services to the full extent stated under the existing law (O’Neil 2017). A follow-up study conducted five years later finds that there has been an increasing number of both public and private hospitals that refuses to provide any abortion service or abortion-related care (O’Neil et al. 2024). Many of these hospitals do not perform abortions, and stated the prohibition of abortion as a reason for their refusal to provide these services (O’Neil et al. 2024).

In addition to increasing abortion stigma, a key reason for the refusal to provide abortion services in the public sector is the ‘performance score’ system. Within this system, abortions receive fewer performance points than other obstetric procedures such as deliveries or caesarean sections, thereby discouraging medical staff from providing abortion services. While the private sector is less subject to bureaucratic control, its unregulated and discriminatory pricing practices disproportionately impact young, single, and socioeconomically disadvantaged women (Pekkurnaz 2020).

Wider Context: Pronatalism and Demographic Policies in Turkey

The abortion politics of Turkey should be considered within the wider political context. Erdoğan’s conservative AKP came to power in 2002 and gradually reversed many policies of earlier governments. A notable shift has taken place on demographic policies. Since 1960, Turkey emphasized control of population growth in order to facilitate economic development (Yüksel 2013). This changed in 2007 under AKP when the 5-year plan of the State Planning and Organization called for the first time for a return to pronatalist policies. While this came as a response to rapid population aging, pronatalism also fits very well with the Islamist and conservative background of AKP and Erdoğan. Erdoğan strategically used public speeches and informal messages (e.g. urging women to have at least three children on multiple occasions) as a policymaking tool to shape public opinion without the need for major legal reforms (Saluk 2023). The government legitimises its pronatalist measures and further consolidates its position as the ‘righteous state’ by emphasising demographic anxieties, such as low birth rates (Saluk 2023). Moreover, the increasing emphasis on pronatalism both reflects and reinforces the significant rise in anti-gender movements in Turkey and worldwide. These movements are accompanied by promotion of traditional gender norms and familialism, which often position motherhood as central to women's identity and social role (Kancı et al. 2023).

The government’s pronatalism extended beyond mere rhetoric. Aksoy and Billari (2018) show that by mobilizing a clientelistic local welfare system, AKP was able to increase marriage and fertility rates since 2004 in districts under its control compared with districts that were controlled by the opposition parties. The current study complements this earlier literature on Turkey’s pronatalist policies by expanding on the politics of abortion.

Legal Framework, Access and Abortion Stigma

The liberalization of abortion is often considered a crucial step toward ensuring safe and accessible abortion services and abortion-related care. Lifting barriers against abortion can also be a significant step towards altering anti-abortion sentiment and alleviating abortion stigma at the individual, societal and governmental levels (Kumar et al. 2009). However, the legal status of abortion does not always align with the prevailing governmental discourse. Even in contexts where abortion is legal, anti-abortion sentiment fueled by political and religious leaders may create barriers against abortion access and foster public misinformation about abortion availability (Sambaiga et al. 2019). Thus, access to safe abortion depends not only on the permissive legal framework but also on a permissive social and political environment (Berer 2017).

This disconnect between legal framework and abortion practice can undermine women’s reproductive rights, primarily through perpetuating stigma against abortion. Abortion stigma can be produced and reproduced by various social, political and demographic processes and can lead to substantial discrimination and status loss for the affected (Kumar et al. 2009). The emergence of the abortion stigma may push individuals to seek abortion under cover and pursue unsafe or clandestine methods, which can have severe consequences on maternal morbidity and mortality (Grimes et al. 2006). Furthermore, healthcare providers, particularly those employed in state hospitals, may feel pressured and threatened by rising anti-abortion sentiment, leading them to be reluctant to perform abortions (Erkmen 2020).

Moreover, the resurgence of abortion stigma can contribute to the underreporting of abortion experiences or the misreporting of them as spontaneous pregnancy loss. This can occur due to an increasing reliance on unsafe or illegal abortion methods and growing discriminatory norms toward individuals who seek or have had abortions. Additionally, in contexts where abortion is stigmatized, there is often a lack of knowledge and information about abortion procedures and ambiguity surrounding different pregnancy experiences (Sambaiga et al. 2019). Definitions of abortion are shaped by social and contextual norms, and do not always align with biomedical definitions of pregnancy, abortion, and miscarriage (VandeVusse et al. 2023). Moreover, policy restrictions on abortion can further influence how people understand what constitutes an abortion, often creating confusion about the legal status of certain procedures (Buchbinder et al. 2025). In Turkey, social desirability bias in abortion data and misreporting of abortion events, particularly following the abortion debates in 2012, have significantly increased (Saraç & Koç 2020). This shift may reflect a greater reluctance to disclose abortion experiences, as well as changes in how individuals define and perceive abortion in the context of anti-abortion rhetoric and growing restrictions on access to abortion services.

The stigma against abortion is not experienced uniformly. Instead, it intersects with various social, economic, and political systems, and may exacerbate existing social and health inequalities. Abortion stigma is deeply embedded in power relations, with structural factors playing a critical role in shaping exposure to stigma, the ability to navigate it, and its further implications (Strong et al. 2023). For instance, women with lower financial resources often endure stronger abortion stigma (Moore et al. 2021) as they may feel a greater need to keep their abortion experiences secret (Shellenberg 2010). They also receive less financial and social support from their close environment, which, in turn, leads them to seek clandestine abortion methods (Ganatra & Hirve 2002).

Empirical studies in Turkey reveal that socioeconomically disadvantaged women are more likely to resort to unsafe abortion methods when access to abortion in the public sector is limited, further reinforcing their vulnerability (Pekkurnaz et al. 2021). Additionally, the stigma surrounding abortion contributes to a higher likelihood of misreporting abortion experiences as spontaneous pregnancy loss, especially for women with lower socioeconomic status (Saraç & Koç 2020). These consequences reflect the intersection between abortion stigma and other socioeconomic inequalities in Turkey and illustrate how this interplay exacerbates existing social and reproductive vulnerabilities.

Data and Methods

Analytical Sample

We used six waves of Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (hereafter TDHS), which was administered every five years between 1993 and 2018. TDHS is a nationally representative survey which collects data on fertility, marriage, reproductive health, and various socioeconomic indicators from women aged 15 to 49. The individual response rates across the waves were above 80 percent. We pooled together all available 1993-2018 waves of TDHS resulting in a sample of 47,667 women. However, some survey waves included all women (ever- or never-married) aged 15 to 49 while other waves sampled only ever-married women in that age range. To accurately compare abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth rates over time, we considered only ever-married women in all our analyses. This resulted in a total sample size of 40,854 ever-married women.

There were very few missing observations regarding pregnancy termination results. However, information on age at first birth and ideal number of children exhibit a higher proportion of missing observations ( nine percent and eleven percent, respectively). After excluding these missing observations, the final sample size was 32,990.

Variables

We used three outcome variables based on respondents’ self-reported pregnancy experiences: whether they had ever experienced an abortion (0=no, 1=yes), a miscarriage (0=no, 1=yes), or a stillbirth (0=no, 1=yes). The experience of different pregnancy outcomes was collected separately using the following questions: ‘Have you ever had a pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage/induced abortion/stillbirth?’. We used the interview year as the main independent variable, as we aim to document changes in different non-live birth trends after the abortion debate that took place in 2012. Interviews were conducted every five years from 1993 to 2018 and we designated year 2008 (the wave before the political abortion debate) as the reference category.

To ensure that observed changes in non-live birth rates are not due to confounding socio-demographic factors, we adjusted our models for various factors. These include age, age at first birth, age at first marriage, ideal number of children, total number of children, mother tongue (1=Turkish, 2=Kurdish, 3=Arabic, 4=Other), educational attainment, urban residence, contraception use (0=no contraception, 1=folkloric methods, 2=traditional methods, 3=modern methods), and marital status (1= married, 2=widowed, 3=divorced, 4=separated), along with region of residence fixed-effects. We also reported unadjusted coefficients for survey waves.

Additionally, we examined two moderating factors, educational attainment and household wealth index, to investigate whether the changes in non-live birth trends varied among different socioeconomic groups. To do so, we introduced a binary variable that identifies whether the respondent has less than secondary degree or more, and we made use of TDHS’ pre-constructed wealth index variable, which divides the distribution of household wealth among the respondents into 5 equal quintiles. These two variables were interacted with the interview year variable. These interactions were added in subsequent steps. Note that when we interacted household wealth quintiles with survey year, we only used the last four surveys (2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018), as the TDHS introduced the household wealth index only in 2003. In Table A1 (Appendix) we present the summary statistics of the variables included in the empirical analysis.

We first estimate the changes in abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth trends between 1993 and 2018 using a linear probability model (LPM). We are primarily interested in the coefficient of the year 2013 which shows the difference between 2013 and the reference year of 2008, i.e., before and after the 2012 abortion debate. Additionally, we consider the coefficient for year 2018 to examine whether the changes in pregnancy outcomes following the abortion debate, if any, were temporary or long-lasting. In the baseline model (Model 1, 3, 5), we document changes in different pregnancy experiences over 25 years. In the adjusted model (Model 2, 4, 6) we account for an array of socio-demographic characteristics along with region fixed effects. Below we present the equation of Models 2, 4, 6:

Yijp = β0 + β1yeari + β2-9Xij + regionr + ε

where Yijp represents the experience of abortion (Model 2), miscarriage (Model 4) or stillbirth (Model 6) at the time of the interview, indicates the year interview was conducted, is the vector for time variant and invariant socio-demographic control variables which are age, years of education, total number of children, age at first birth, age at first marriage, ideal number of children, ethnicity, marital status and contraceptive use. The term represents region of residence fixed effects. In our models, we estimate (Huber-White-Sandwich) standard errors that are robust to non-normality represented with e.

We then examine whether the changes in abortion, miscarriage or stillbirth experiences vary by educational attainment or by household wealth. To do so, we first fit our models separately by the subgroups. We then introduce interaction terms between year and education, and between year and household wealth in separate steps. We use these models with interactions to estimate predicted probabilities of experiencing the three pregnancy outcomes for each survey year, broken down by educational attainment and household wealth.

Results

Trends in Abortion, Miscarriage and Stillbirth

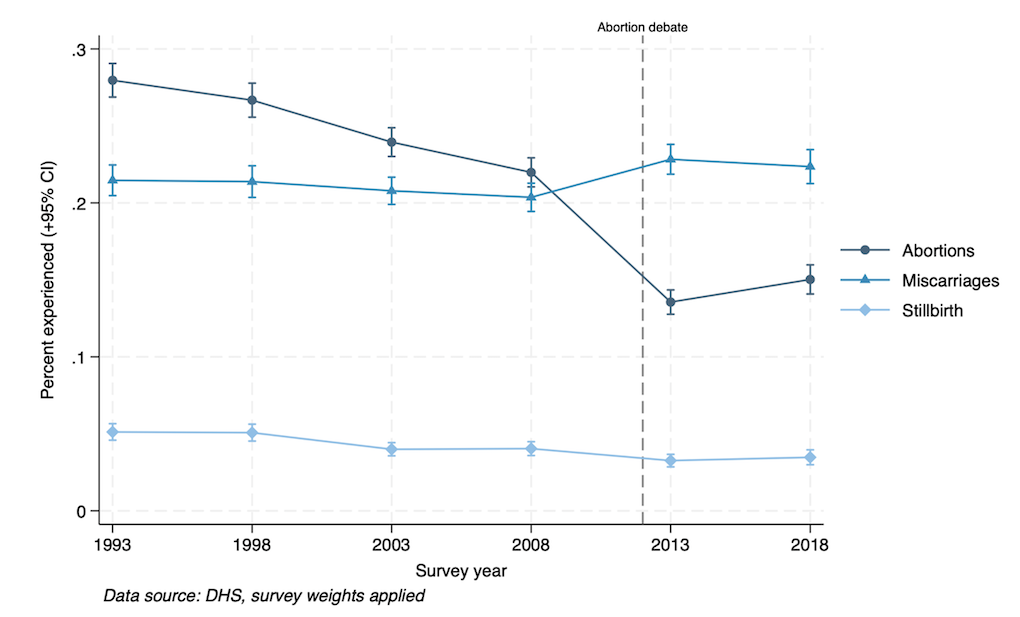

Figure 1 presents the proportion of ever-married women who reported experiencing abortion, stillbirth or marriage at least once over the period 1993-2018. Despite the steady decline in abortions between 1993 and 2008, we observe a rapid drop from 2008 to 2013. Although, the proportion of women who reported ever experiencing an abortion slightly increased in 2018 compared with 2015, the difference between 2013 and 2018 is not statistically significant. This suggests that the decline after 2012 was not temporary. This decline cannot be due to more widespread contraceptive use in 2013, for there is no considerable change in contraceptive use between 2008 and 2013. Moreover, when we control contraceptive use in Model 2 (see Table 1), the 2008-2013 difference increases even further.

Figure 1: Proportion of ever-married women who experienced at least one event over time.

Another striking finding concerns miscarriage. Reported miscarriage rates remain relatively constant between 1993 and 2008, but we register an unexpected increase in 2013 compared with 2008. The increase in reported miscarriage rates persists in 2018. The proportion of women who reported experiencing a stillbirth gradually and mildly decreased over time.

Multivariate Analysis

Table 1 displays the results obtained by fitting our regression models. The findings from Model 1 indicate that reported abortion rates follow a declining trend over time. This is in line with Turkey’s demographic transition and improvement in reproductive health outcomes as well as the dissemination of modern contraceptive use (Koc 2000, Yavuz 2006). Between 2008 and 2013, however, the likelihood of reporting an abortion declined more strongly than the typical trend, consistent with the pattern shown in Figure 1. In 2013, the probability of reporting an abortion declined by almost seven percentage points compared to 2008 (p<0.01). The decline persists in 2018, with women being almost six percentage points less likely to report an abortion in 2018 than in 2008. Interestingly, compared to 2008, while the probability of reporting a miscarriage remained statistically unchanged between 1993 and 2003, it increased by 3 percentage points in 2013 and 2018 (for both years p<0.01). Compared to 2008, the probability of reporting a stillbirth declined by one percentage point in 2013 and in 2018. The results from Model 1, 3, and 5 remain largely unchanged when we account for an array of socio-demographic characteristics in Model 2, 4, and 6.

As to the notable control variables, education is positively associated with reported abortion, while negatively associated with reported miscarriage and stillbirths. Ethnicity does not seem to correlate with either of the three outcomes. Contraceptive use is linked with reported abortion but not with reported miscarriage or stillbirths. Age, age at first birth, age at first marriage, marital status, ideal and actual number of children are factors that are all linked with the three outcomes. Importantly, adding these control variables does not alter the estimated time trends in any substantial way.

|

Abortion |

Miscarriage |

Stillbirth |

|

||||

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

|

|

|

Ref: 2008 |

|

||||||

|

1993 |

0.096** |

0.130** |

0.006 |

0.004 |

0.006 |

0.005 |

|

|

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

(0.007) |

(0.008) |

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

|

|

|

1998 |

0.078** |

0.101** |

0.012 |

0.009 |

0.006 |

0.005 |

|

|

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

|

|

|

2003 |

0.044** |

0.048** |

0.015+ |

0.010 |

-0.001 |

-0.002 |

|

|

(0.009) |

(0.008) |

(0.009) |

(0.008) |

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

|

|

|

2013 |

-0.065** |

-0.070** |

0.030** |

0.022** |

-0.011** |

-0.013** |

|

|

(0.007) |

(0.006) |

(0.007) |

(0.007) |

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

|

|

|

2018 |

-0.059** |

-0.074** |

0.026** |

0.023** |

-0.011** |

-0.013** |

|

|

(0.007) |

(0.007) |

(0.008) |

(0.008) |

(0.004) |

(0.004) |

|

|

|

Age |

0.015** |

0.004** |

0.002** |

|

|||

|

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

(0.000) |

|

||||

|

Ref: Less than secondary |

|

||||||

|

Secondary and above |

0.018** |

-0.035** |

-0.008** |

|

|||

|

(0.006) |

(0.006) |

(0.003) |

|

||||

|

Urban |

0.038** |

0.017** |

-0.008** |

|

|||

|

(0.005) |

(0.005) |

(0.003) |

|

||||

|

Age at first birth |

-0.013** |

0.018** |

0.005** |

|

|||

|

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

|

||||

|

Ideal number of children |

-0.005** |

0.016** |

0.004** |

|

|||

|

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.001) |

|

||||

|

Age at first marriage |

-0.002 |

-0.019** |

-0.006** |

|

|||

|

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

(0.001) |

|

||||

|

Ref: Turkish |

|

||||||

|

Kurdish |

-0.006 |

-0.005 |

-0.005 |

|

|||

|

(0.007) |

(0.008) |

(0.004) |

|

||||

|

Arabic |

-0.001 |

0.021 |

-0.010 |

|

|||

|

(0.014) |

(0.017) |

(0.008) |

|

||||

|

Other |

-0.008 |

0.018 |

-0.002 |

|

|||

|

(0.018) |

(0.019) |

(0.009) |

|

||||

|

Ref: Never used contraception |

|

||||||

|

Folkloric methods |

0.036 |

|

0.081 |

|

-0.017 |

|

|

|

(0.047) |

(0.056) |

(0.027) |

|

||||

|

Traditional methods |

0.052** |

0.011 |

-0.009+ |

|

|||

|

(0.007) |

(0.010) |

(0.005) |

|

||||

|

Modern methods |

0.150** |

0.018* |

-0.006 |

|

|||

|

(0.007) |

(0.009) |

(0.005) |

|

||||

|

Ref: Married |

|

||||||

|

Widowed |

-0.057** |

-0.050** |

-0.008 |

|

|||

|

(0.016) |

(0.016) |

(0.009) |

|

||||

|

Divorced |

0.063** |

-0.006 |

-0.015* |

|

|||

|

(0.019) |

(0.017) |

(0.006) |

|

||||

|

Separated |

0.065* |

-0.024 |

0.006 |

|

|||

|

(0.029) |

(0.027) |

(0.015) |

|

||||

|

Total number of children |

-0.014** |

0.018** |

0.005** |

|

|||

|

(0.002) |

(0.002) |

(0.001) |

|

||||

|

Region FE |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Observations |

32,990 |

32,990 |

32,990 |

32,990 |

32,990 |

32,990 |

|

|

R-squared |

0.023 |

0.127 |

0.001 |

0.037 |

0.001 |

0.017 |

|

Notes: Regional fixed effects are included in all models but suppressed for brevity. Robust standard errors in parentheses.*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, +p<0.1

Table 1: The predictors of abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth.

Variation in Time Trends by Education Level

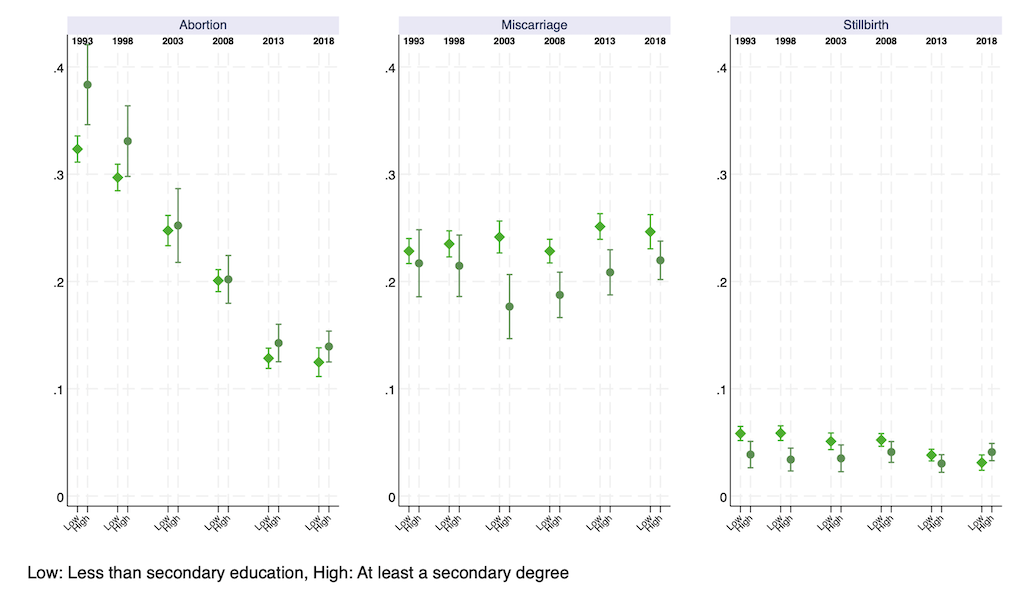

As a next step, we investigate whether the changes in reported abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth trends vary by educational attainment. Looking at the abortion outcomes, we find that both low- and high- educated women experienced a similar decline since 1993, with higher educated women experiencing a slightly steeper decline (See Column 2 of Tables A2 and A3 in the Appendix for the particular comparison of 2018, 2013 and 2008). On the other hand, the change in reported miscarriage and stillbirth experiences in 2013 versus 2008 seems to be primarily driven by women with less than secondary degree: in 2013 versus 2008, low educated women were 2.3 percentage points more likely to report a miscarriage experience, and 1.5 percentage points less to likely to experience a stillbirth. While more educated women show similar trends (an increase in reported miscarriage and decrease in reported stillbirths in 2013 vs 2008), the 2008 and 2013 differences were insignificant for them. In 2018, women in both education categories were more likely to report a miscarriage than in 2008, but the differences are only weakly statistically significant (p<0.1).

Figure 2 displays the predicted probability of reported experience of abortion, miscarriage or stillbirth by survey year and the respondent’s education level. The findings show that the overall probability of reporting an abortion decreaseds almost linearly for both education groups since 1993, although this trend appears to have stabilised by 2018. Regarding miscarriage, however, starting from 2003, women with lower education have a significantly higher probability of reporting miscarriage compared to those with at least a secondary degree. Compared to 2008, the probability of reporting a miscarriage in 2013 is estimated to be significantly higher for women who have less than secondary education while the same difference is statistically insignificant for their higher educated counterparts. Between 2013 and 2018, miscarriage reporting remained at similar levels across both education groups, but the differences between these two groups were no longer statistically significant. Lastly, compared with higher-educated women, lower-educated women had higher chances of reporting a stillbirth in 1993 and 1998, although this difference mostly narrowed in 2003 and remained unchanged in the subsequent survey waves.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth experience by survey year and education level

Variation in Time Trends by Household Wealth

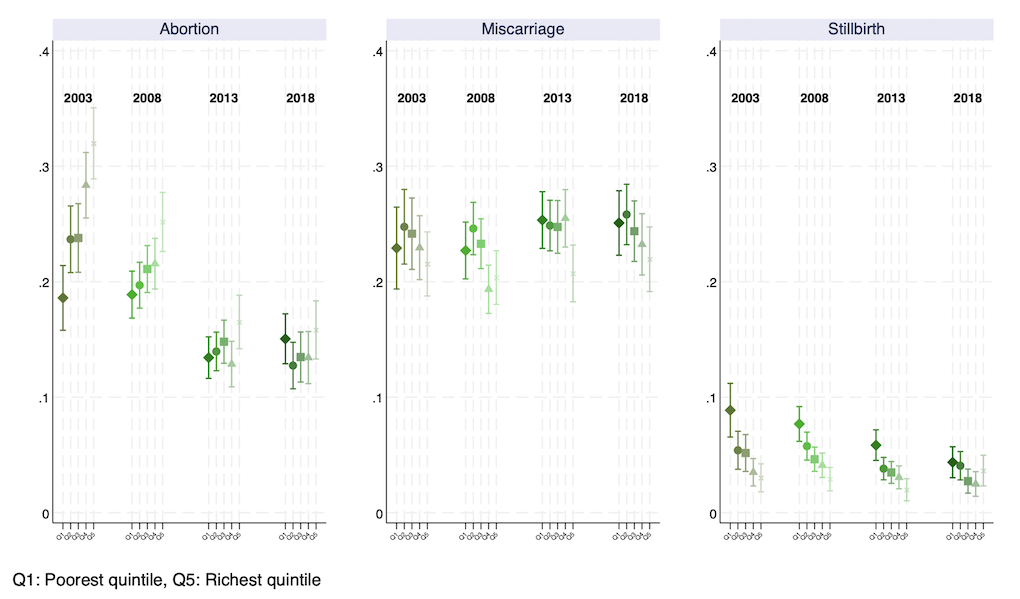

We further examined whether the trends in reported abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth between 2008 and 2018 varied by household wealth. We found that, compared to 2008, all wealth groups were less likely to report an abortion in 2013 and 2018. The most substantial decrease between 2008 and 2013, nearly nine percentage points, was observed in the fourth and fifth wealth quintile (see Column 2 of Tables A4-A8 in the Appendix). Between 2008 and 2018, the largest reduction in abortion reporting occurred in the richest quintile. Furthermore, the increase in miscarriage rates in 2013 was primarily driven by the first (2.8 percentage points, p<0.1) and fourth (6.4 percentage points, p<0.01) wealth quintiles, while the probability of reporting miscarriage remained statistically unchanged for other groups. Over the longer period between 2008 and 2018, we only estimate a statistically significant increase in miscarriage reporting among women in the fourth wealth quintile.

Figure 3 plots the predicted probability of reporting an abortion, miscarriage, or stillbirth by survey year and household wealth quintiles. For abortion, significant declines from 2008 to 2013 were estimated for all wealth groups, with notable decreases in the first and fourth wealth quintiles. While the probability of reporting an abortion was around 19% for respondents in the first quintile in 2003 and 2008, it dropped to 13.5% in 2013. Moreover, for respondents in the fourth quintile, the probability of reporting an abortion declined by almost nine percentage points from 2008 to 2013 (21.2 in 2008 to 12.3 in 2013). In 2013, the fourth quintile had the lowest probability of reporting an abortion among all wealth groups, despite being the second highest in previous years. It is also remarkable that after the political abortion debate in 2013, the wealth gradient in reported abortion, which is clearly observed in 2003 and 2008, largely disappeared. A similar pattern emerges in 2018 where the probability of reporting an abortion remained at levels comparable to 2013, while the wealth gradient seems to have decreased.

For reported miscarriage, compared to 2008, we observed an increase in 2013 for the first and fourth wealth quintiles, although the difference was statistically significant only for the fourth quintile. For other wealth groups, the probability of reporting a miscarriage remained unchanged between 2003 and 2013. In 2013, women in the richest quintile had a significantly lower probability of reporting miscarriage, whereas by 2018 the wealth gradient in miscarriage reporting had also diminished. Finally, while overall reported stillbirth rates declined over the years, the trends by wealth quintiles remained the same, with the first and poorest quintile recording the highest rates. Only in 2018, we estimate a slight but unexpected increase in the probability of reporting a stillbirth for the richest quintile.

Figure 3: Predicted probability of abortion, miscarriage and stillbirth experience by survey year and wealth quintiles

Discussion

Access to safe abortion is crucial for ensuring women’s physical and mental well-being. Restrictive laws and conscientious objection by health-care providers jeopardize access to safe abortion services, by pushing induced abortion operations to private clinics or places with untrained staff and health-harming methods (Autorino et al. 2020, Harris & Grossman 2020). Moreover, even liberal laws may not guarantee access to abortion, when they are constrained by socially and politically defined gestational limits and health reasons, especially in the absence of clear guidelines for implementation or support by political and social institutions. In this study we focus on Turkey to examine how abortion and other pregnancy ending experiences have changed after the government’s anti-abortion debate in 2012. While abortion has been legal in Turkey since 1983, there are strong suggestions that it has been banned de facto or made extremely difficult to access to since 2012.

Our findings show that the likelihood of reporting an abortion followed a downward trend over time. This declining trend is particularly notable during the period 2008 – 2013 in which the likelihood of reporting an abortion declined at an unprecedented pace and then remained roughly the same level between 2013 and 2018 even after controlling for contraception use, the number of children, marital status, and other sociodemographic variables. At the same time, while the probability of reporting a miscarriage remained statistically unchanged between 1993 and 2008, it increased by three percentage points (nearly 15 percent) in 2013, from about 0.20 in 2008 to 0.23 in 2013. The reported miscarriage rate remained similar in 2018, at 0.22. From 2008 to 2018, the stillbirth rates declined by 1.1 percentage points, consistent with the declining trend observed in previous years.

We see several possible explanations for this abrupt, out-of-trend decline in reported abortion and a simultaneous increase in reported miscarriage in 2013 and in 2018 compared with 2008. While these explanations are distinct, they are not mutually exclusive. Most likely, all these processes are in operation simultaneously and partially responsible for the trends that we observe.

First, the rapid decline in reported abortion might be related to reduced accessibility of abortion services, which in turn pushed women towards methods that increased miscarriages. As mentioned above, the legal basis for abortion was reconsidered by the government with an anti-abortion campaign that resulted in a draft bill in 2012. Since then, there has been suggestive scholarly evidence on informal restrictions on abortion services, particularly in public hospitals (O’Neil 2017, O’Neil et al. 2024). Research indicates that only 7.8 percent of state hospitals provide abortion services without restriction as to reason, and in two regions (West Marmara and East Black Sea) there are currently no state hospitals that provide abortion unless for medical necessity (O’Neil 2017). Furthermore, scholars argue that the introduction of a performance scheme in 2003 for hospitals exacerbated the problem of accessibility of reproductive health services. Since very few reproductive services were covered within these performance schemes, hospitals and clinics are disincentivized from investing in such services (Agartan 2012, Pekkurnaz et al. 2021, Bump et al. 2014). Along with the political pressure, budgetary concerns could have led public hospitals to provide limited abortion services. This explanation is also consistent with our findings, broken down by household wealth. We find that abortion rates have been lowest among poorer households who are more likely to rely on public health services that are under pressure; and the poorest households show a significant increase in reported miscarriages.

Second, the denial of abortion services in both public and private clinical settings has been a key factor driving individuals to seek medical abortion through online networks such as Women on Web (Atay et al. 2022). Since medical abortion is not legal in Turkey, it is difficult to assess the extent to which it has replaced clinical abortion services. One possible explanation for the observed decline in reported abortions (and the simultaneous increase in reported miscarriages) may be that medical abortion is not always perceived or defined as abortion. Evidence from the United States suggests that clinical intervention shapes public perceptions of abortion; for instance, individuals are more likely to classify miscarriage management with medical intervention as abortion (VandeVusse et al. 2023). In Turkey, the turn to self-managed medical abortion in response to limited clinical access may similarly influence how individuals frame and report their experiences, potentially contributing to the decline in abortion reporting in surveys.

Third, given the stable trend of miscarriage rates prior to 2008, the unexpected rise in miscarriages in 2013 might signal a misreporting issue regarding abortion and miscarriage experiences. The stigmatizing political discourse for abortion may have pushed women to misreport their experiences. Related to this point, given the political pressures on hospitals and doctors, abortion operations might be under-recorded or mis-recorded under other types of pregnancy termination by the medical staff. These explanation are consistent with the results of previous research, which show increasing levels of misreporting of induced abortion in surveys, potentially due to social stigmatization and the political environment criminalizing abortions (Saraç & Koç 2020). Furthermore, women undergoing abortion in Turkey have voiced concerns about breaches of confidentiality and privacy by medical staff, particularly within public health services (Atay et al. 2022, MacFarlane et al. 2017). These concerns are compounded by fears that the Ministry of Health monitors pregnancies and other reproductive events through centralized databases (Saluk 2022), and that having an abortion record could lead to profiling or future repercussions. In this context of institutional distrust, the reluctance to report abortion experiences (or the tendency to report them as miscarriages) can be seen as a form of resistance and navigation in response to state surveillance of reproductive lives. Hence, it is possible that women may feel hesitant to disclose their abortion experiences in surveys such as the TDHS which is conducted by a public university with funding from the Ministry of Health and the Presidency of Strategy and Budget (former Ministry of Development).

Our results did not uncover any education gradient in declining reported abortion rates, which may suggest that access to abortion is becoming difficult even in private clinics. In line with our findings, O’Neil et al. (2024) show that 12.7 percent of the hospitals in their Turkish sample stated that their staff prefer to not perform abortion and 33 percent claim incorrectly that abortion is illegal in Turkey in 2021. Moreover, we find that the increase in reported miscarriage after 2008 is mainly driven by women who have less than secondary education. This resonates with prior research that abortion misreporting may be more prevalent among women from lower socioeconomic strata (Saraç & Koç 2020). Political environments that condemn abortion can perpetuate abortion stigma especially when it intersects with other sources of discrimination – e.g. class inequalities. Moreover, it can create ambiguity around the definition of diverse pregnancy experiences and may undermine the availability of public information on abortion and other reproductive procedure which can be particularly harmful for socioeconomically disadvantaged women (Sambaiga et al. 2019).

Lastly, we found that while all wealth groups are less likely to have an abortion after 2008, in 2013 only respondents in the first and fourth (lowest and second highest) wealth quintiles had a higher probability of experiencing a miscarriage. When we compare the probability of experiencing miscarriage by wealth quintiles, we see a significant increase only for the fourth quintile and between 2008 and 2013. This finding is somewhat surprising as wealthier women in Turkey are less likely to choose public services for abortion (Pekkurnaz et al. 2021) and they are less likely to misreport their abortion experiences as miscarriage (Saraç & Koç 2020). This finding can be interpreted in the light of the socioeconomic gradient of abortion and public service use in Turkey. On average women with higher SES are more likely to have (or to report having) abortions (Ankara 2017). Given this, one might expect that the reduced access to abortion creates a stronger disruption in the lives of high-SES women. Moreover, compared to those in the richest quintile, women in fourth quintile might have more limited financial resources to undergo abortion in private clinics or abroad and they may be more exposed to a stronger social stigma against abortion. Consequently, they may have turned to self-induced termination methods or are more likely to report their abortion experiences as miscarriage.

Conclusion

Our findings shed light on how a politically repressive environment for reproductive rights could translate into a de facto abortion ban in public hospitals and manifest itself as stronger social stigma on abortion. This can happen even when, at least on paper, abortion is legally allowed. These anti-abortion pressures undermine the reproductive health rights and the quality of reproductive health care as well as reinforce existing social disparities. Moreover, they may push women to use health-harming methods to carry out abortion, or be reluctant to report their experiences in surveys as a form of resistance and navigating growing governmental pressures and surveillance on women’s reproductive experiences.

Our findings suggest a call for reinstating full access to abortion services, as allowed by the Turkish law. This call for reinstating full access to abortion services in Turkey is also closely tied to growing concerns about women’s reproductive autonomy in an increasingly pro-natalist political environment. In 2021, Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention arguing that the convention promotes norms that are ‘incompatible with Turkish family values’.[5] Moreover, the government’s recent declaration of 2025 as the “Year of the Family” and its promotion of marriage and higher fertility that is framed through the lens of traditional family values and national population growth further reflects a broader ideological shift. This increasing emphasis on traditional family values and gender roles is also situated within the wider context of reproductive backsliding and the anti-gender movement that has gained momentum across Europe and the US since the 2010s. These movements have consistently targeted reproductive rights, including abortion access, contraception, and assisted reproductive technologies (Kuhar & Patternet 2017). Turkey’s case parallels similar developments in other countries (e.g. Spain and Poland) where conservative governments have restricted abortion.

Lastly, our findings offer insights into the broader implications of restricting abortion services on reproductive health data collection. In environments characterized by abortion restrictions, survey-based measurement of abortion, miscarriage, and stillbirth can become challenging due to increasing abortion stigma, barriers against accessing abortion services and growing uncertainty around the definition and perception of abortion as well as other pregnancy outcomes. Moreover, declining abortion figures may reflect governmental narratives aimed at reducing abortion rates overall; however, they may mask the actual experiences of women seeking reproductive care, their negotiations with medical staff and their social circles, and their willingness to disclose these experiences in government-supported surveys. Our analysis thus highlights that reproductive health data cannot be examined and interpreted independently from the political and social context in which it is collected. Overall, our study underscores the importance of ensuring the full implementation of reproductive rights to ensure better reproductive health data quality and to reduce social and health inequalities associated with their restriction.

Orcid IDs

Selin Köksal https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0158-1348

Francesco Billari https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4717-6129

Ozan Aksoy https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2170-6099

References

Agartan, T. (2012) Gender and health sector reform: Policies, actions and effects. In S. Dedeoglu & A.Y. Elveren (Eds.) Gender and society in Turkey: The impact of neoliberal policies, political Islam and EU accession (pp. 155–172). I.B.Tauris.

Aksoy, O., & Billari, F. C. (2018) Political Islam, marriage, and fertility: Evidence from a natural experiment. American Journal of Sociology, 123(5), 1296–1340. https://doi.org/10.1086/696193

Ankara, H. G. (2017) Socioeconomic variations in induced abortion in Turkey. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(1), 99–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932016000158

Atay, H., Dedeoglu, B. E., Balkanci, U. B., Sadak, E., & Gomperts, R. (2022) Access to formal abortion services and demand for medical abortion in Turkey: A mixed-method study. Authorea Preprints.

Autorino, T., Mattioli, F., & Mencarini, L. (2020) The impact of gynecologists’ conscientious objection on abortion access. Social Science Research, 87, 102403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102403.

Berer, M. (2017) Abortion law and policy around the world: In search of decriminalization. Health and Human Rights, 19(1), 13-27.

Berro Pizzarossa, L., & Sosa, L. (2021) Abortion laws: The Polish symptom of a European malady? Ars Aequi, 2021, 587-595. http://clacaidigital.info/handle/123456789/1497

Buchbinder, M., Arora, K. S., McKetchnie, S. M., & Sabbath, E. L. (2025) Medical uncertainty in the shadow of Dobbs: Treating obstetric complications in a new reproductive frontier. Social Science & Medicine, 369, 117856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117856

Cindoglu, D., & Unal, D. (2017) Gender and sexuality in the authoritarian discursive strategies of ‘New Turkey’. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 24(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506816679003

Erkmen, S. (2020) Türkiye’de kürtaj: AKP ve biyopolitika. İletişim Yayınları.

Esengen, S. (2024) ‘We had that abortion together’: Abortion networks and access to il/legal abortions in Turkey. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 26(9) 1119-1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2023.2301410

Ganatra, B., & Hirve, S. (2002) Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters, 10(19), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(02)00016-2

Grimes, D. A., Benson, J., Singh, S., Romero, M., Ganatra, B., Okonofua, F. E., & Shah, I. H. (2006) Unsafe abortion: The preventable pandemic. The Lancet, 368(9550), 1908–1919. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6

Harris, L. H., & Grossman, D. (2020) Complications of unsafe and self-managed abortion. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(11), 1029–1040. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMra1908412

Kancı, T., Çelik, B., Bekki, Y. B., & Tarcan, U. (2023) The anti-gender movement in Turkey: An analysis of its reciprocal aspects. Turkish Studies, 24(5), 882–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2022.2164189

Koc, I. (2000) Determinants of contraceptive use and method choice in Turkey. Journal of Biosocial Science, 32(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932000003291

Kuhar, R., & Paternotte, D. (Eds.). (2017). Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against equality. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

Kumar, A., Hessini, L., & Mitchell, E. M. (2009) Conceptualising abortion stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(6), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050902842741

Küng, S. A., Darney, B. G., Saavedra-Avendaño, B., Lohr, P. A., & Gil, L. (2018) Access to abortion under the heath exception: A comparative analysis in three countries. Reproductive Health, 15 (107), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0548-x

Lindberg, L., Kost, K., Maddow-Zimet, I., Desai, S., & Zolna, M. (2020) Abortion reporting in the United States: An assessment of three national fertility surveys. Demography, 57(3), 899–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00886-4

MacFarlane, K. A., O’Neil, M. L., Tekdemir, D., Çetin, E., Bilgen, B., & Foster, A. M. (2016) Politics, policies, pronatalism, and practice: Availability and accessibility of abortion and reproductive health services in Turkey. Reproductive Health Matters, 24(48), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.11.002

MacFarlane, K. A., O’Neil, M. L., Tekdemir, D., & Foster, A. M. (2017) “It was as if society didn’t want a woman to get an abortion”: A qualitative study in Istanbul, Turkey. Contraception, 95(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.190

Millar, E. (2022) Maintaining exceptionality: Interrogating gestational limits for abortion. Social & Legal Studies, 31(3), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639211032317

Moore, B., Poss, C., Coast, E., Lattof, S. R., & van der Meulen Rodgers, Y. (2021) The economics of abortion and its links with stigma: A secondary analysis from a scoping review on the economics of abortion. PloS One, 16(2), e0246238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246238

O’Neil, M. L. (2017) The availability of abortion at state hospitals in Turkey: A national study. Contraception, 95(2), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.09.009

O’Neil, M. L., Ramaswamy, A., & Altuntaş, D. (2024) Population politics, reproductive governance and access to abortion in Turkey. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 26(10), 1316-1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2024.2317734

Pekkurnaz, D. (2020) Employment Status and Contraceptive Choices of Women With Young Children in Turkey. Feminist Economics, 26(1), 98–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1642505

Pekkurnaz, D., Ökem, Z. G., & Çakar, M. (2021) Understanding women’s provider choice for induced abortion in Turkey. Health Policy, 125(10), 1385–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.07.015

Saluk, S. (2022) Datafied pregnancies: Health information technologies and reproductive governance in Turkey. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 36(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12675

Saluk, S. (2023) Fraternal natalism: Demographic anxieties and the righteous state in Turkey. Women’s Studies International Forum, 98, 102751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102751

Sambaiga, R., Haukanes, H., Moland, K. M., & Blystad, A. (2019) Health, life and rights: A discourse analysis of a hybrid abortion regime in Tanzania. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1039-6

Saraç, M., & Koç, İ. (2020) Increasing misreporting levels of induced abortion in Turkey: Is this due to social desirability bias? Journal of Biosocial Science, 52(2), 213–229. doi:10.1017/S0021932019000397

Shellenberg, K. M. (2010) Abortion stigma in the United States: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives from women seeking an abortion. The Johns Hopkins University.

Strong, J., Coast, E., & Nandagiri, R. (2023) Abortion, stigma, and intersectionality. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of social sciences and global public health (pp. 1579–1600). Springer.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2023) World Population Policies 2021. United Nations. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210000949

VandeVusse, A. J., Mueller, J., Kirstein, M., Strong, J., & Lindberg, L. D. (2023) “Technically an abortion”: Understanding perceptions and definitions of abortion in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 335, 116216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116216

Yavuz, S. (2006) Completing the fertility transition: Third birth developments by language groups in Turkey. Demographic Research, 15 (15), 435–460. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.

Yüksel, Y. (2013) In search of a pronatalist population policy for Turkey: A gender perspective. Economic and Social Research Council Seminar Posttransitional Fertility in Developing Countries: Causes and Implications. Oxford.

[1] United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. See: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/SexualHealth/INFO_Abortion_WEB.pdf

[2] According to UN Population Division data, 60% of the women of reproductive age lives in contexts where abortion is broadly legal. https://reproductiverights.org/maps/worlds-abortion-laws/

[3] See: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-18297760

[4] http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/yazarlar/melis-alphan/kurtaj-yasasi-var-uygulayan-yok-40253029, http://www.milliyet.com.tr/yasa-yok-ama-kurtaj-yasak/gundem/detay/1838845/default.htm,

https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/gundem/2018/04/23/doktorlar-kurtaji-yasak-saniyor/

[5] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/07/turkeys-withdrawal-from-the-istanbul-convention-rallies-the-fight-for-womens-rights-across-the-world-2/

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 2 (2025), Issue 3 CC-BY-NC-ND