An interpretive discourse network analysis of post-pandemic economic recovery across EU institutions

Research Article

Charlotte Godziewski1* and Tim Henrichsen 2

1Department of International Politics, City St George’s, University of London, UK 2School of Government, The University of Birmingham, UK *Corresponding author: Charlotte Godziewski, charlotte.godziewski@city.ac.ukPost-COVID economic recovery agendas emphasise health, sustainability, and resilience. However, how to make economies more health-promoting – and how the relationship between economy and health is best governed – is contestable and normative. This article offers an interpretive use of Discourse Network Analysis to explore the ideas underlying the EU’s economic recovery discourse and the place of health within it. It analyses how documents published in 2020 by various EU institutions talk about health and about economic recovery, shedding light on the relationship between ideas on these topics, and how they form a multifaceted discourse. We suggest that the discourse on economic recovery is underpinned by three ‘idea clusters’ that represent facets of the overarching discourse: ‘Economic and Monetary Union’, ‘Social Europe’, and ‘European Health Union’. We show how socioeconomic ideas, largely from the ‘Social Europe’ cluster, along with health security, are the main bridges that hold the discourse together by argumentatively connecting economic recovery and health. We also highlight that, except for the European Central Bank, idea clusters do not reflect specific institutions, but that all clusters feature in parts of institutions, underscoring that it is important not to treat institutions as monoliths, but to unpack the nuances present within them.

Contested Ideas of Health-promoting Economic Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the weaknesses and unsustainability of current economic systems, including within the European Union (Jones & Hameiri 2022, Spash 2021). It has shown how health crises can have devastating economic effects. At the same time, the pandemic exposed how unsustainable and inequality-generating economic systems make populations less healthy, and more vulnerable to health crises (Bambra et al. 2021). In short, the health of economies and that of people are related, and understanding that relationship is of growing interest among researchers (Lynch 2023, Ralston et al. 2023, Schrecker & Bambra 2015). Initially, many saw the pandemic as an opportunity to ‘Build Back Better’, suggesting that a post-pandemic economy should be organised around social goals like health and equity. Recovery plans, including in the EU, state as their aim the creation of more sustainable, healthier, and more resilient economies (European Commission 2023). While this is an appealing vision, there are many ways to interpret what this means and to translate these broad goals into concrete action.

Ideas of what a health-promoting economic recovery requires, and looks like, are inherently contestable. ‘Health’ can be understood in many ways, and different understandings of health can have radically different implications for how it can or should be governed (Rushton & Williams 2012). For example, there are important differences between thinking of health in predominantly biomedical terms, compared to thinking about it from within a social ontology (Tseris 2017). Biomedical understandings of health tend to focus more on pathophysiology, and are concerned with the origins of diseases, rather than the origins of health (Mittelmark & Bauer 2017). They seek to single out causes of diseases and target them at an increasingly precise, molecular level. If based on a mainly biomedical understanding of health, the relationship between health and the economy is likely to be focused on healthcare, health systems financing, and health innovation (Hunter 2008). In contrast, health can also be understood as a dynamic ‘outcome of social, cultural, political, economic, and environmental processes’ (Faerron Guzmán 2022, p.2), rather than the state of absence of disease. Thinking about health as continuously shaped by local/global processes that impact social, economic, and environmental realities does not negate the importance of biomedicine, but it broadens the scope of the relationship between economic systems and health. Not only does the scope become broader and more systemic, but the normative nature and implications of this relationship also become apparent.

Our aim in this article is to map and make sense of the place of ‘health’ within the EU discourse of economic recovery emerging in 2020. Our approach is predicated on the assumption that the EU economic recovery discourse is not uniform and ‘pre-orchestrated’, but results from the contingent entanglement of different interacting, distinct but related ideas present across and within different EU institutions. The article is driven by the following research question: How do EU institutions conceptualise the relationship between health and economic recovery? To investigate this question, we undertake a discourse network analysis, mapping ideas around health and economic recovery evoked in EU documents published in 2020. This uses network analysis in an interpretive, post-positivist way. While this combination may be unusual, we argue that compatibility between network analysis and interpretive theory requires ontological and epistemological coherence that depends on how one uses and interprets the method.

Our contribution is twofold. At an empirical level, we offer an analysis, visualisation, and interpretation of how ideas on health and economic recovery put forward in different parts of the EU institutions, relate to each other. Understanding the EU’s discourse of economic recovery as a process resulting from a dynamic network of ideas, allows to better understand the contingencies that lead to a particular way of defining the EU’s economic recovery and its relationship to health. By making an intentional case for combining network analysis and interpretive theory, we also propose a secondary, conceptual contribution aimed at cultivating dialogue across interpretive and quantitative approaches to research.

Ideational Power and Decentred Theory

Delineating the contours of what represents health and what should be thought about as impacting health, is normative and depends on people’s worldviews and beliefs. Aspirations to build a ‘healthier economy’ therefore rest upon assumptions and shortcuts – ideas – around ‘health’, ‘economy’, and the relationship between both. In 2020, the EU started articulating a unified discourse for a health-promoting economic recovery. This discourse does not emerge de novo. It is contextually, historically, and ideationally situated. Following Hajer’s (1993) definition, we conceptualise discourses as ‘an ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categories through which meaning is given to phenomena’ (p.45, emphasis added). We use Béland and Cox’s (2010, p.3, paraphrased) definition of ideas as ‘causal beliefs produced in our minds and connected to the material world via our interpretations […] [positing] connections between things and between people in the world and provid[ing] guides for action’. Our focus in this paper is on the relationship between the overarching discourse, and the individual ideas that constitute it. Concretely, we are interested in how ideas, their interaction and connectedness, become constitutive of the EU economic recovery discourse.

There is a rich scholarship of interpretive international political economy (IPE) that seeks to better understand ideational power, and that treats ideas as constitutive of social reality rather than as variables strategically mobilised within an independently pre-existing social reality (Abdelal et al. 2010, Béland & Cox 2010, Bevir & Rhodes 2016, K. Smith 2013, Schmidt 2008, Wagenaar 2014). Taking ideational power seriously, these interpretive approaches recognise that an understanding of governance cannot be deduced in advance, neither from pre-determined actor interests nor from path dependencies (Bevir 2002). Rather, they argue that social action needs to be understood in a historical, ideational, fundamentally contingent and specific context. When studying governance, these interpretive approaches share a common concern with exploring the relationship between change and continuity, between micro-level agencies and macro-level regularities, and the co-constitution of structure and agency. The relative emphasis placed on either side of this co-constitutive relation varies across the literature, depending on the theoretical position and purpose of the research (Berry 2007). There are also semantic disagreements around what constitutes structure, and whether attempts to avoid its reification simply displace it (M.J. Smith 2008). Engaging in depth with these points of contention is beyond the scope of this article, and we consider interpretive ideational IPE as a broad church within which we situate our article theoretically. From this perspective, we take the general consensus that actors operate within a context of relatively solidified structures and fluid agency. In decentred theory, Bevir and Rhodes (2008) focus on traditions to capture these solidified realities, whereas Schmidt’s (2016) discursive institutionalism talks about ‘background ideas’. The fluid agency manifests as the ‘foreground discursive ability’ of actors to think outside their institutional box (Carstensen & Schmidt 2016) and can drive considerable change especially in abnormal moments where actors question their beliefs (Bevir & Waring 2020, p.10).

For the operationalisation of our analysis, we draw on decentred theory for its useful double hermeneutic of decentring and re-centring. As put by Bevir and Rhodes (2008, pp.729–30): ‘To decentre is to unpack a practice into the disparate beliefs of the relevant actors. It is to recognise that diverse narratives inform the practice of governance. […] To re-centre using […] concepts of “tradition” and “dilemma” is to accept that political scientists can tell different narratives about governance depending on what they hope to explain.’ Our analysis decentres the EU economic recovery discourse to investigate the ideas within it. Mirroring the quote above, we see the EU economic recovery discourse as what they refer to as the ‘practice’. For the sake of feasibility, we limit what they refer to as the ‘disparate beliefs and diverse narratives’ to the ideas we identify in the documents. In doing so, we seek to open up the EU’s economic recovery discourse to make visible the multiplicity and nuanced ideas contained in it, their relational qualities, and how they give shape to the discourse. The subjective analytical story we tell to interpret the network then re-centres the EU economic recovery discourse according to ‘what we hope to explain’, that is, how health features in the discourse of EU economic recovery.

Interpretive Discourse Network Analysis

The conceptual contribution of our paper is its use of network analysis, specifically discourse network analysis (DNA), embedded in the interpretive ideational theoretical framework of decentred theory. DNA is a type of network analysis that allows to measure and visualise how people, organisations, or concepts are related as a network. The method combines content analysis with network analysis (Leifeld 2017, p.5). It is often used to identify discourse coalitions (Hajer 1993) in political debates – networks at the level of actors – but can also be used to understand how ideas are related to each other through actors and the extent to which they form (or do not form) coherent clusters of ideas – networks at the level of ideas. The use of DNA to map relationships between ideas rather than between actors is currently underexplored but promising, especially as an avenue for using it interpretively, as already done by Nagel and Schäfer (2023). The method is inclusive in the sense that it does not impose a pre-defined ontology onto any of its components (e.g. the ideas coded, or the networks themselves), neither does it require a particular approach to content analysis (Leifeld 2020).

Our aims are to decentre and re-centre the EU economic recovery discourse, to better understand how ideas on health, on the economy, and on the relationships between them, come to constitue the overarching economic recovery discourse. We argue that DNA can be an appropriate method for this task. ‘Decentring’ means opening up the discourse to explore the multitude of ideas contained in it and constituting it through their relational qualities. We do this in the first step of our analysis, through coding ideas we find on health and economic recovery and through the network analysis itself, which reveals how the ideas relate to each other. The relational, networked quality of the ideas we explore then allows us to re-centre the discourse, to interpret and tell a story of the place of health within it. We do not argue that the network we generate represents (an approximation of) ‘the truth’ to be uncovered. Rather, the network analysis we generate is the product of the choices we made on how and what to code, measure, and visualise based on what we seek to understand. Our network, therefore, is inherently a product of interpretation and should be understood as such.

Using network analysis interpretively requires consideration of ontological and epistemological coherence (Emirbayer & Goodwin 1994). Network analysis tends to be associated with positivist research aimed at identifying causal relations existing independently of how they are understood. While it may be conventionally used so, there is not necessarily anything inherently positivist about network analysis. Methods are tools with specific characteristics and limits, but ensuring alignment with theory lies in how methods are used and understood – i.e. the methodological link between the theory and the tool (Crossley & Edwards 2016). In the case of using network analysis interpretively, the methodological balance lies in negotiating the foundational tension between the ‘formalism’ often conferred to the method (seeking universal rules) and its ‘relational’ interpretation (understanding contingency and meaning-making) (Erikson 2013, Glückler & Panitz 2021). If the method is used in a way reflexive of these theoretical and ontological undergirdings, it mirrors the theoretical concerns of interpretive IPE around understanding regularities contexually while avoiding determinism. Focusing on the relationality of ideas, DNA can align with a number of theoretical positions, including interpretivism, provided the process and results are understood coherently.

The back and forth between identifying disparate ideas and looking at their relational qualities, between coding and generating networks, allows interpretations of the relationship between structure and agency. We interpret the network of ideas (how the ideas relate to each other), as the more solidified, ‘structural’ emerging quality of the ideas constituting the discourse. Looking at it in this way also sheds light on how central or powerful some ideas are within the discourse, which ideas are most strongly connected to each other, and also which ideas connect otherwise disjointed parts of the discourse. Interpreting the EU economic recovery discourse as a network of ideas can thereby shed light on the ideological drivers underlying the discourse, as well as on what ideas act as the ‘binding agent’ that holds the different parts of it together. One could zoom in deeper and ethnographically investigate how these central, powerful ideas are themselves solidified through everyday practices of individual people. While this is beyond the scope of our paper, our network offers a useful starting point for such deeper, more granular investigation.

This article is concerned with exploring the co-constitution of agency and structure, looking at both ideas as cognitive beliefs of actors, and at their solidifying relational, networked qualities. An interpretive use of DNA is well-suited here, as it renders possible a ‘relationally explicit treatment [of discourses and the actors that speak them]’ (Leifeld 2017, p.5). Using DNA interpretively also avoids presenting discourses as ahistorical and decontextualised (Steensland 2008). By decentring the EU economic recovery discourse and analysing the multitudes of ideas on health in it, we avoid making totalising, deterministic claims. And by interpreting the network of ideas, we capture regularities and re-centre the discourse with specific attention to how health features within it.

Decentring

First, we identified and coded ideas on health and economy contained in the EU economic recovery discourse. Second, we mapped how these ideas are networked, how they relate to each other. These steps ‘decentred’ the discourse, unpacked it into disparate yet connected and intertwined ideas that constitute it.

|

EU institution |

Types of documents included in the coded sample |

Number of documents |

|

European Commission |

Institutional papers, communications; press releases/Q&A; recommendations/proposals; staff working documents; reports from DG BUDGET; DG ECFIN; DG SANTE; SEC GEN; JRC |

19 |

|

Council |

Council conclusions; council regulation; joint statements; meting summaries; reports from Council of EU; European Council; Eurogroup |

14 |

|

European Parliament |

Reports and opinions from AGRI; BUDG&ECON; BUDG; ECON; EMPL; ENVI |

15 |

|

EU legislation (Council and EP) |

Regulations |

5 |

|

European Central Bank |

Blogs; working papers |

26 |

|

Total |

79 |

|

Table 1: Overview of documents included

Data Collection

We included publications across EU institutions during the early stages of the pandemic (in the year 2020). Capturing this broad architecture (rather than the framing in a single policy document, for example) can shed light on how – through what contingent interactions of ideas put forward by different actors – a dominant discourse of economic recovery crystallised at EU level. Our data collection required us to be inclusive, purposeful, and follow an emergent approach (Emmel 2014). We gathered online documents from the European Commission (EC), the main relevant intergovernmental bodies (European Council, Council of the European Union, and the Eurogroup), the European Central Bank (ECB), and the European Parliament (EP), as well as relevant EU regulations. We used very broad search terms (‘COVID’ or ‘coronavirus’ or ‘pandemic’ and/or ‘recovery’) to capture as many publications as possible. The results yielded were then filtered manually: documents were included if they were deemed to be mainly about COVID economic recovery (see Table 1 for overview of the documents collected).

Inductive Coding

The documents were formatted as text files and uploaded in the open-source Discourse Network Analyzer (DNA) software. The DNA software is a ‘qualitative content analysis tool with network export facilities’ (Leifeld n.d.). In the DNA software, text passages/statements can be coded by attributing a ‘concept’ to them (the ideas), the ‘actor’ (or organisation) that made the statement, as well as a dummy variable indicating whether the actor agrees or disagrees with the statement. To capture differences within EU institutions and avoid treating them as uniform, we differentiated between parts of the EU institutions - ‘sub-institutions’ (EC Directorate Generals, EP Committees, etc), i.e., we coded DG SANTE and DG BUGDET as two separate actors even though they are both part of the European Commission.

Our general process was to code concepts manually and inductively, identifying statements that provided answers to the following questions:

- What does economic recovery look like/what defines economic recovery?

- What does economic recovery require?

- How is health mentioned in the context of economic recovery?

- What are important considerations for the economic recovery?

- What processes and principles are needed for enabling the economic recovery?

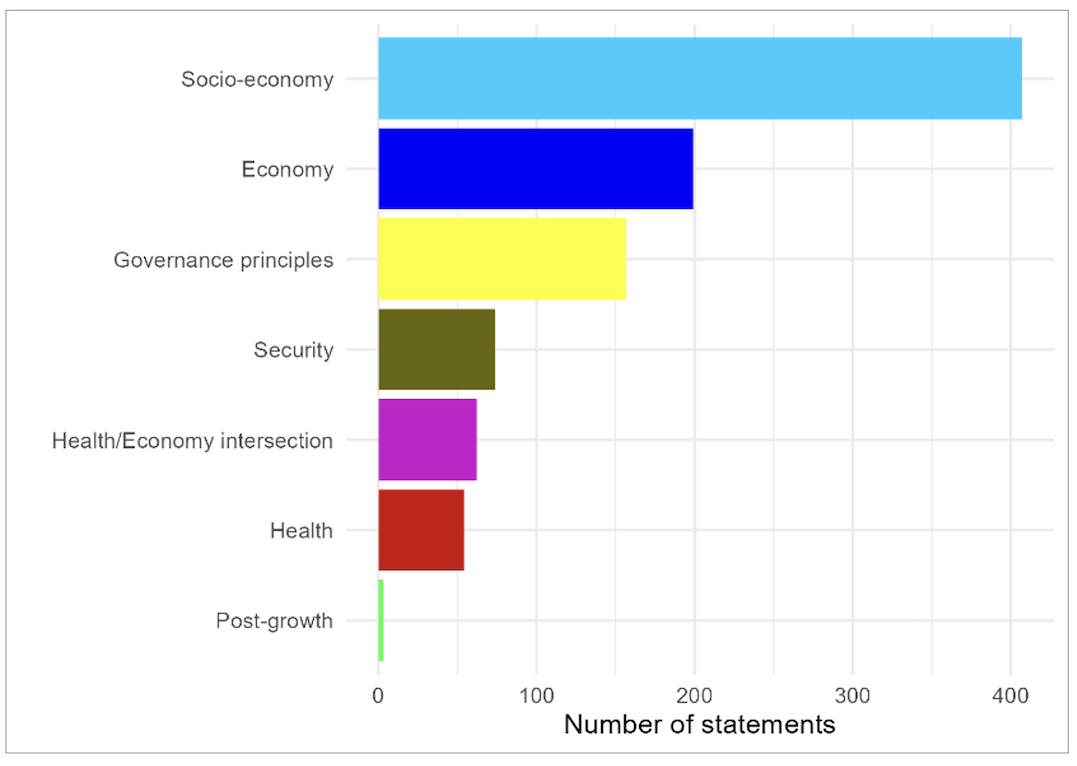

In the 79 documents, we coded 991 statements that we identified as pertaining to the questions listed above. We created colour-coded categories of ideas based on our interpretation of what concepts fit together, what concepts share a same logic/underlying rationale or are about the same topic (see Figure 1). The colour-coding is helpful to get an intuitive grasp of the network visualisation – it helps make sense of what kinds of ideas are similar and where they are situated on the graph.

The light blue category refers to economic ideas that link the economy to social/environmental factors (other than health, which is its own category coded in purple). The ideas most referred to within that category include the notion that the recovery needs to be green/environmentally sustainable, that economic recovery requires fiscal stimulus, and that it needs to foster cohesion and solidarity. The idea that economic recovery requires more ‘high quality’, secure employment, as well the accent on digitalisation, was also included in this category. The reason we included digitalisation in this category, is because digitalisation was often referred to as a way to promote a green recovery (along the lines of the so-called ‘twin transition’ and reskilling related to the ‘just transition’) and a way to promote social inclusion.

Figure 1: Frequency of concept type within study documents

The dark blue category represents ‘purely’ economic ideas which, in their phrasing, do not explicitly connect the economy with other factors. Among the most often referred to economic idea features that recovery requires growth, that the COVID crisis requires driving a consumption-led economic recovery, in which private investment and the banking sector are crucial. We can describe these kinds of ideas as following an orthodox economics logic.

The light green category includes ideas that are explicitly critical of the continuous pursuit of economic growth. It includes a reference to the wellbeing economy (along the lines of the doughnut economic model developed by Raworth 2017) as well as a statement on the need to decouple wellbeing from consumption. These ideas were not referred to often enough to feature in the network and remained very marginal, perhaps unsurprisingly given their radical nature.

The purple, red, and khaki categories all include statements on health. The khaki category relates to ideas about health security and represent the most used way to talk about health. The purple category includes ideas that explicitly relate health and economy together (for example: ‘economic growth is good for health’, or ‘recovery requires financial investment in health’, or links between single market and health via digitalisation and innovation). Here, the idea that recovery requires investment in health, mostly referring to health systems sustainability and supporting the pharmaceutical sector, was the most prevalent one. The red category includes references to health that are mentioned within the document about economic recovery, but that are not directly or explicitly put in relation to economic governance, even though they have implications for economic recovery (for example, statements about the importance of social determinants of health and health inequalities, the idea that the EU needs to be more active in health, health educat]ion). Here, the most often referred to idea was the notion that the EU should be more involved in health.

Finally, the yellow category includes statements about governance principles that matter for the economic recovery (for example, references to budgetary flexibility, evidence-based policymaking, stakeholder consultations, impact assessment, and knowledge brokering). By far the most often referred to governance principle is the need for flexibility, followed by an accent on the temporary and exceptional nature of recovery instruments, and the importance of policy coordination, especially between monetary and fiscal policy.

Some categories were easy to define and delineate, for example the category of ideas on governance principles invoked as necessary to enable the economic recovery (in yellow). Mostly, however, categories are interpretive and fluid. For example, the distinction between concepts from ‘economy’ (dark blue) and ‘socio-economy’ (light blue) are based on our judgement on the emphasis of an idea or even of the emphasis in the phrasing of an idea. We coded both in different shades of blue because they both pertain to economic ideas, but we categorised them based on the extent to which they reflect more orthodox economic ideas limited to the economy ‘for its own sake’ (dark blue) or whether economic ideas were linked to social and/or environmental factors (light blue). In some cases, this involved making subjective decisions based on different relative emphases that two phrasings of a similar idea imply. For example, our rationale for coding ‘Fiscal stimulus’ in light blue and ‘Consumption-led economic recovery’ in dark blue was that, even though they can converge in practice, the former phrasing places emphasis on the relationship between social and economic factors, fiscal stimuli being generally redistributive and aimed at reducing inequalities. The latter phrasing is more market-oriented and decontextualises the social factors underlying consumption. The accent here is on overall increase in consumption, less on how different social groups and their purchasing power are affected differently.

Network Analysis

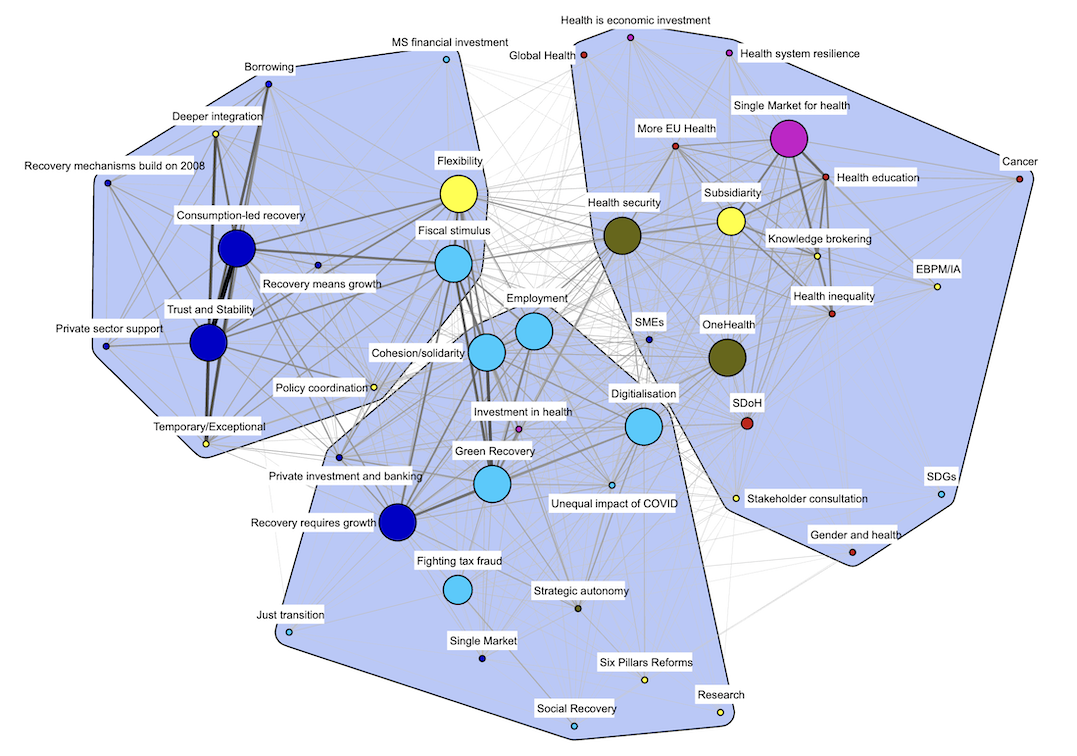

To explore the role and interdependence of ideas when EU institutions talk about economic recovery and health, we visualise an idea x idea one-mode network (Figure 2) in which ideas are linked if they have been endorsed by the same actors, reflecting argumentative alignment between the ideas. This means that two ideas are linked through a tie if the same institution mentions them both. The ties between ideas are also weighted, depending on how often one or many actors refer to the same ideas. Each idea is visualised as a node, and nodes are colour-coded according to the categories outlined in Figure 1. To enhance the interpretation of the network structure, ideas only mentioned once were excluded. Furthermore, we set a tie weight threshold according to the median value of the tie weight distribution (0.857). This means that we only retained strong ties between nodes (ties stronger than the median value of all ties) in the network visualisation. This ensures that only relatively robust connections between ideas are visualised in the network. Darker and thicker ties indicate a stronger tie weight between ideas and therefore a stronger argumentative compatibility: the thicker, darker the tie between two ideas, the stronger their cognitive connection. The frequency of mentions of ideas is also accounted for here, to ensure that the connection is meaningful (i.e. when idea A is mentioned, the likelihood of idea B to be mentioned is very high and vice versa), and not merely circumstantial (ideas A and B are mentioned together because idea A is mentioned all the time anyway). This is also known as the “average activity” normalisation (Leifeld 2017). We also applied the Louvain community detection algorithm (Blondel et al. 2008), represented by the blue hyperplanes covering the network nodes. Community detection algorithms (such as Louvain) identify clusters within a network in which a subgroup of nodes is strongly connected to each other while being only sparsely connected to other clusters. In this application, these clusters can be interpreted as ‘idea clusters’ – these can be understood as groups of ideas that contribute to specific angles of the discourse on economic recovery and health.

Figure 2: Discourse network showing idea clusters in the discourse on economic recovery and health

The discourse network reveals three distinct idea clusters within the debate: an upper left cluster, primarily composed of dark blue nodes representing economic ideas (which we label the ‘Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)’ cluster); a central cluster, or ‘Social Europe’, associated with socio-economic ideas (light blue); and an upper right cluster, that we label ‘European Health Union (EHU)’, where most health-related ideas (red, khaki, and purple) are concentrated. The distinct nature of the individual clusters suggests that the different parts of EU institutions tend to primarily rely on ideas of one cluster in their public statements. For instance, parts of EU institutions issuing an idea related to health tend to refer to other health-related ideas rather than (socio-)economic ideas, thus explaining the network clusters. We can understand, for example, that DG SANTE mentions more than one health idea, and the ECB more than one economic idea.

Nonetheless, we also observe certain ideas connecting the individual clusters through argumentative ties. These ideas represent important connections between the otherwise more isolated clusters that make up the overall, multifaceted discourse of economic recovery. We visualise these ‘connecting ideas’ via the node sizes, which correspond to a node’s bridge betweenness centrality value (Jones et al. 2019). ‘Bridge betweenness centrality’ is a measure that quantifies the extent to which one node lies on the shortest path between two other nodes that belong to different clusters. Higher values indicate that a node serves as a connecting idea, facilitating argumentative connections between ideas of different clusters. Thus, to effectively create argumentative coherence between idea clusters (i.e., between the EMU and the EHU) and form the overarching discourse of economic recovery, some ideas are put in relation through these connecting ideas. Put simply, if an idea is represented by a large node, it means it connects other ideas from different clusters. These big nodes should be understood as bridges between clusters – they feature in the rationales that connect economy – health – and social ideas.[1] These connecting ideas confer coherence to the economic recovery discourse, with some central ideas connecting otherwise separate ideas around economic recovery and health.

We further investigate connecting qualities of the network, this time of idea clusters (rather than of individual ideas). To do so, we calculated the EI-Index for the different clusters (Table 2). Developed by Krackhardt and Stern (1988), the EI-Index measures the openness of subgroups to other groups within a network by comparing the number of external ties between clusters to the internal ties within a cluster. A value of -1 indicates complete homophily, where nodes only connect within their own group, while a value of 1 indicates complete heterophily, where nodes connect exclusively to nodes in other groups.

|

EHU |

Social Europe |

EMU |

|

|

EHU |

- |

-0.02 |

-0.52 |

|

Social Europe |

0.13 |

- |

-0.09 |

|

EMU |

-0.23 |

0.09 |

- |

Table 2: EI-Index for the three idea clusters in the discourse on economic recovery and health for EHU (European Health Union) Social Europe and EMU (Economic and Monetary Union)

The EI-Index reports that the EHU cluster is weakly closed compared to its ties to the Social Europe cluster and strongly closed towards the EMU cluster. Social Europe, on the other hand, is rather open towards the ideas of the EHU cluster and weakly closed towards the EMU cluster. Finally, the EMU cluster is rather closed towards the EHU cluster and rather open towards Social Europe. These findings emphasise that while health and economy are not inherently linked by mutually shared ideas, incorporating ideas from the Social Europe cluster is crucial for creating argumentative compatibility and further underscores the role of the Social Europe cluster as a key cluster with the most predominantly connecting ideas. Concretely, this can be interpreted as the ‘Social Europe’ cluster binding the disparate group of economic ideas and the group of health ideas together, giving coherence to the EU economic recovery discourse as a whole.

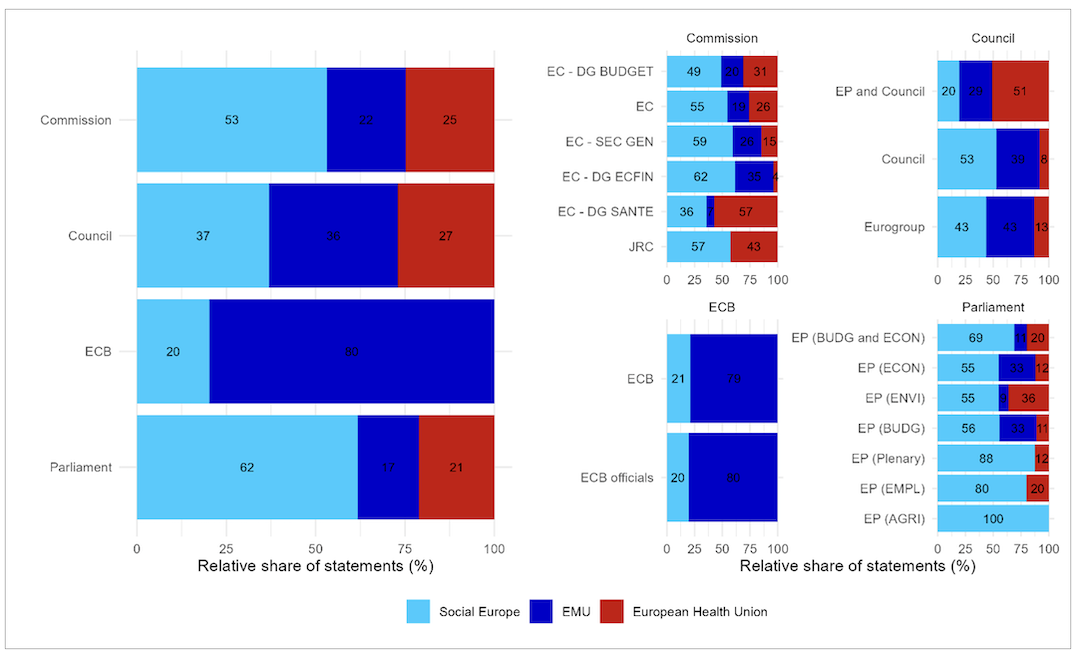

Ideas Across Institutions

Finally, we also want to interpret which EU institutions are primarily responsible for shaping these cluster structures. Figure 3 illustrates the relative share of statements from EU institutions directed towards the three identified idea clusters. The left plot visualises the relative share for aggregated EU institutions and the smaller plots to the right visualise the relative shares of sub-institutions. The ECB, given its specific institutional focus, predominantly concentrates on ideas related to the EMU. However, aside from the ECB, all (sub) institutions show a relatively even distribution of statements across the different clusters. This indicates that the network structure is not shaped by isolated institutions, but ideas are widely shared across these various institutions. By disaggregating the EU institutions and looking at ideas within their different parts, the plots to the right support the notion that the EU institutions are not monoliths, and that different parts of the institutions emphasise different ideas[2]. While most sub-institutions exhibit a shared strong focus on ideas from the Social Europe cluster, we can also observe some variation towards EMU/EHU ideas. For example, while most DGs within the European Commission place a significant emphasis on the Social Europe idea cluster, DG SANTE primarily addresses ideas from the EHU cluster. In contrast, this DG rarely draws on EMU ideas, which are the focus of DG ECFIN. The DG ECFIN, however, tends to disregard EHU-related ideas. Similar patterns can be seen among the European Parliament’s sub-institutions.

Looking at the distribution of ideas in that way underscores the agency of policymakers. How they talk about economic recovery and health is not pre-determined by an a priori homogenous EU-wide structure. Except for the ECB (which has a very specific and technical mandate), our data suggest that perspectives on economic recovery and health are not dictated by institutions compartmentalised along different ideas but are collectively shared among and within sub-institutions. As such, we can suggest that the ideas within institutions shape the discourse more than the institutions as an a priori structure.

Figure 3: Share of actor statements per idea cluster

Re-centring

Having decentred the EU economic recovery discourse, unpacked disparate ideas and their relationship, we now ‘re-centre’ it, drawing on concepts of ‘tradition’ and ‘dilemma’ to interpretively make sense of these patterns of ideas and relations. To do this, we contextualise the ideas clusters within their historical trajectory – denoting the role of tradition – and highlight departures from those traditions – denoting the role of dilemma.

Interpreting Ideas Clusters

We observed that socio-economic ideas, such as Employment, Cohesion/Solidarity, and Green recovery, function as the primary connecting ideas, linking the ideas in the Social Europe cluster with those in the EMU and EHU clusters, and vice versa. This connecting role could be understood as reflecting EU policymakers’ awareness of the social (and socioeconomic) determinants of health (SDoH). Although explicit references to the SDoH and health inequalities do not connect clusters, ideas like cohesion, solidarity, and employment do act as a bridge between the ideas on health and on the economy.

Looking at it through the lens of tradition, we are reminded that ‘Social Europe’ was already a conciliatory concept, dating to the 1980s and 1990s. The then European Commission president Jacques Delors promoted EU integration by balancing the demands of those advocating for a more social, democratically legitimate EU, and of free-market advocates, through giving Single Market integration a social identity (Jabko 2006). This has since been part of the EU’s identity – at least at a discursive level – and has been adapted over time. The Social Europe rhetoric is present, for example, in the Lisbon agenda and its soft governance experimentation intended to promote member state convergence in social areas and link economic and social governance (see: the Open Method of Coordination). This same logic remains visible in the ‘NextGenerationEU’ COVID recovery instrument set up by the European Commission. The main part of this instrument, the ‘Recovery and Resilience Facility’ (RRF) has been integrated within the European Semester, which is the EU’s fiscal coordination cycle. At the same time, the presence of ‘Social Europe’ at a discursive level, does not necessarily guarantee its translation into action, and researchers have criticised the erosion of EU social policy since the financial crisis (Graziano & Hartlapp 2019). Furthermore, many of these socio-economic ideas are somewhat consensual in nature. Ideas like a ‘green’ recovery or solidarity are broad, in some cases vague but widely accepted among EU institutions and the public, making them socially favourable and easy bridges for linking economic recovery and health, but not necessarily concrete. This might also explain the high prevalence and connecting quality of socioeconomic ideas (Figure 1).

We also find connecting ideas within the other clusters. In the EHU cluster, we observe that connecting ideas are the ones about health security, and the importance of the single market in ensuring the adequacy of supply chains for pharmaceuticals (‘Single Market for health’). While ‘Single Market for health’ was coded as an idea about the intersection between health and economy (purple), the accent on medical countermeasures is also a feature in the EU’s health security agenda (Bengtsson & Rhinard 2019). The network suggests that health security and an accent on pharmaceuticals is a chosen avenue for EU institutions to talk about health in the context of COVID recovery. This is consistent with previous research, notably on the EU’s new Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority (Godziewski & Rushton 2024). The term ‘EHU’ was crafted by European Commission president von der Leyen in 2020 in response to the pandemic. As an idea cluster, it is the newest and least institutionalised one. But the trend of EU integration in health, especially through health securitisation and exploiting the synergies between health security and single market, is not new and has been expanding more rapidly since 2001, especially in response to health crises (de Ruijter 2019). Subsidiarity is also a relatively important connecting idea from the EHU to other clusters. It suggests that policymakers who talk about health and ideas from another cluster often link those ideas by talking about the extent to which the EU is mandated to act on health. This, in conjunction with ‘more EU in health’ being the idea in the red category referred to the most times, is illuminating because it reflects the EU’s historical concern over the extent to which it has the required competence to act on health, and whether it should have more health competences (Brooks et al. 2023).

In the EMU cluster, we find four connecting ideas: ‘consumption-led recovery’, ‘trust and stability’, ‘fiscal stimulus’, and ‘flexibility’. Interestingly, the two latter ideas are not dark blue as one might expect, but one pertains to process (flexibility) and the other one is an idea coded as a socioeconomic one (the need for fiscal stimulus). The prominence of ‘fiscal stimulus’ in what is predominantly a ‘purely economic’ cluster may be interpreted as an instance dilemma, a moment where a set way of working shifts. Such an interpretation echoes the argument made that the EU’s response to the pandemic has been significantly different, significantly less austerity-driven than its response to the 2008 crisis (Keune & Pochet 2023). The EU’s response to the financial crisis was marked by a punitive austerity agenda which many agree failed to protect citizens from hardship and failed to support a prompt economic recovery. Because of the nature of the COVID crisis, the response this time has not been one of blame and invoking ‘moral hazard’ and instead drew more on a sense of solidarity (Ioannidis 2020). The consensus around what response is appropriate has been deemed less austerity-driven, instead calling for redistributive measures (Buti & Fabbrini 2023). The ECB even took on a leadership role in the early COVID days, with the launch of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), the first major EU recovery instrument, in March 2020. It also emphasised the importance of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy to promote a prompt recovery. Comparing 2008 with the pandemic response, Quaglia and Verdun (2023) argue that the ECB demonstrated policy learning at an inter-crisis and intra-crisis level.

Our discourse network analysis illuminated how ideas contained in the EU economic recovery discourse relate to each other through different clusters that are connected via certain ideas. This latter step of re-centring the discourse offered an interpretation of the idea clusters drawing on historical, political, and contextual specificities of EU integration and governance. In our interpretation, we have drawn on notions of traditions and dilemmas to make sense of how this discourse of economic recovery crystallised, and how it engages with health. Our interpretation of elements of the network highlighted the conciliatory role of the ‘Social Europe’ concept, the story of EU integration and weak competences in health, and the shift away from austerity rhetoric in 2020 compared to 2008, to better understand the EU economic recovery discourse as a whole, and how health features within it.

Conclusion

‘Health’ can be understood and governed in different ways. Our interpretive use of DNA embedded in decentred theory has shed light on the ways in which ideas on health, economic recovery, and the relationship between them feature within the EU discourse articulated in 2020 on economic recovery. The DNA methodological approach provided a valuable resource to systemically disaggregate the discourse into its individual ideas and idea clusters. This empirical evidence was then re-centred by embedding idea clusters in their historical and political context.

At first sight, the economic recovery discourse put forward by EU institutions presents as coherently orchestrated and regular, with some ideas like ‘green recovery’, ‘cohesion/solidarity’, and ‘fiscal stimulus’ being repeated very often by everyone. Our analysis aimed to go deeper and decentre this discourse. Looking at publications from 2020 from across EU institutions, we identified various ways in which economic recovery is talked about and defined, and ideas on what it requires and how health is mentioned, as well as what governance processes are required to enable it. This revealed a multitude of disparate ideas, which we then analysed as a network, to explore how these ideas relate to each other.

Our work of decentring the economic recovery discourse shows three ‘idea clusters’ that make up different facets of the discourse: a cluster focused on economic ideas (EMU), one focused on health (EHU), and one focused on socioeconomic ideas (‘Social Europe’). Idea clusters can be understood as distinct ‘facets’ of the overall discourse. We were particularly interested in understanding how these idea clusters connect, because this sheds light on how – through what ideational trajectories – the overarching discourse of economic recovery is ‘held together’ coherently. Measures of bridge betweenness centrality, read in conjunction with the EI-index, indicated that socioeconomic ideas from the Social Europe cluster (for example employment, cohesion/solidarity, and green recovery) establish the link between the EMU and EHU clusters. ‘Purely’ economic ideas and ‘purely’ health-related ideas are not necessarily talked about together, but they connect when policymakers talk about ‘Social Europe’ ideas. Our analysis also suggests that, apart from the ECB, institutions do not neatly align with one idea cluster. Rather, all idea clusters are present in different parts of each institution. This suggests that EU institutions like the EC should not be treated as monoliths, but that policymakers within all institutions talk about different ideas. We can interpret this in an agential way. The overall discourse is shaped by the ideas put forward by EU policymakers within the institutions, across different parts of the institution and their relationships, perhaps more than by pre-determined institutional structural power.

We then re-centred the discourse. This means we interpreted the network we produced in context, drawing on ‘tradition’ and ‘dilemma’ to make sense of it and of the place of health within it. The historical relevance of ‘Social Europe’ is worth emphasising here. It has always been about reconciling (whether successfully or not) constitutional asymmetries between economic and social integration in EU governance. It underpins the soft governance innovations that promote social convergence, notably through fiscal coordination, which has been seen as an avenue for the EU to further integrate in health (Greer 2014). We can see the continuity here with the COVID recovery instruments. We can also see reflected in the network a point of departure from past ways of handling crises. Others have argued that the consensus on the initial economic response to the pandemic was considerably less austerity-driven then the response to the Eurozone crisis, and indeed we see the prominence of the (connecting) idea that recovery requires fiscal stimulus located in the EMU cluster. Finally, our analysis also suggests that, when EU policymakers talk about health in the context of COVID economic recovery, they connect the two topics through an emphasis on health security and pharmaceuticals, shaping how health becomes governed, and are often also compelled to mention subsidiarity. The prominence of these ideas can be understood through the lens of tradition, in the context of the EU’s gradual integration in health through crises and in spite of the weakness of its official competences in health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kat Smith, Justin Waring, and Mark Bevir for inviting us to take part in this special issue and the workshop on ‘decentring public health’, and we thank all the other participants. Thank you also to Sharon Friel and the Planetary Health Equity Hothouse for the opportunity to present this paper at the School of Regulation and Global Governance (ANU). We are grateful to Katherine Fierlbeck, Tammy Hervey and all the participants in the workshop organised by the Jean Monnet European Centre of Excellence at Dalhousie University and the City St George’s Institute for the Study of European Law (ISEL). Thanks, too, to Gabriel Siles-Brügge and the reviewers for their helpful engagement and feedback.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Orcid IDs

Charlotte Godziewski https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7036-2387

Tim Henrichsen https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3037-7162

References

Abdelal, R., Blyth, M., & Parsons, C. (Eds.) (2010) Constructing the international economy. Cornell University Press.

Bambra, C., Lynch, J., & Smith, K. (2021) The unequal pandemic - COVID-19 and health inequalities. Policy Press.

Béland, D., & Cox, R. (Eds.) (2010) Ideas and politics in social science research. Oxford University Press.

Bengtsson, L., & Rhinard, M. (2019) Securitisation across borders: the case of ‘health security’ cooperation in the European Union. West European Politics, 42(2), 346-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1510198

Berry, C. (2007) Rediscovering Robert Cox: Agency and the ideational in Critical IPE. Political Perspective 1(1) 1-29. https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/schools/soss/politics/political-perspectives/Volume%201%20Issue%201/CIP-2007-01-08.pdf (Accessed 11 August 2025)

Bevir, M. (2002) A decentered theory of governance. Journal des Économistes et des Études Humaines, 12(4), 475-497. https://doi.org/10.2202/1145-6396.1073

Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R.A.W. (Eds) (2016) Rethinking governance - Ruling, rationalities and resistance. Routledge.

Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R.A.W. (2008) The differentiated polity as narrative. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 10(4), 729-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2008.00325.x

Bevir, M., & Waring, J. (2020) Decentring networks and networking in health and care services. In: M. Bevir & J. Waring (Eds.), Decentring health and care networks: Reshaping the organization and delivery of healthcare (pp. 1–16). Springer International.

Blondel, V.D., Guillaume J.-L., Lambiotte, R., & Lefebvre, E. (2008) Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 10, P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008

Brooks, E., de Ruijter, A., Greer, S.L., & Rozenblum, S. (2023) EU health policy in the aftermath of COVID-19: neofunctionalism and crisis-driven integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(4), 721-739. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141301

Buti, M., & Fabbrini, S. (2023) Next generation EU and the future of economic governance: towards a paradigm change or just a big one-off? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(4), 676-695. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141303

Carstensen, M., & Schmidt, V. (2016) Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive i]nstitutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 318-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

Crossley, N., & Edwards, G. (2016) Cases, mechanisms and the real: The theory and methodology of mixed-method social network analysis. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 217-85. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3920

De Ruijter, A. (2018) EU external health security policy and law. Amsterdam Centre for European Law and Governance Working Paper Series 2018-02. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3144212

Emirbayer, M., & Goodwin J. (1994) Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency. American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1411–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2782580

Emmel, N. (2014) Purposeful sampling. In: N. Emmel (Ed.), Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research: A realist approach (pp. 33-44). SAGE Publication.

Erikson, E. (2013) Formalist and relationalist theory in social network analysis. Sociological Theory, 31(3), 219-242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113501998

European Commission (2023) Recovery plan for Europe. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/recovery-plan-europe_en#:~:text=NextGenerationEU%20is%20a%20more%20than,the%20current%20and%20forthcoming%20challenges (Accessed 11 August 2025).

Faerron Guzmán, C.A. (2022) Complexity in global health- Bridging theory and practice. Annals of Global Health, 88(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3758

Glückler, J., & Panitz, R. (2021) Unleashing the potential of relational research: A meta-analysis of network studies in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 45(6), 1531-1557. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211002916

Godziewski, C., & Rushton, S. (2024) HERA-lding more integration in health? Examining the discursive legitimation of the European Commission’s new Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 49(5), 831-854. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-11257008

Graziano, P., & Hartlapp, M. (2019) The end of social Europe? Understanding EU social policy change. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1484-1501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531911

Greer, S.L. (2014) Three faces of European Union health policy: policy, markets, and austerity. Policy and Society, 33(1), 13-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.03.001

Hajer, M.A. (1993) Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice: The case of acid rain in Great Britain. In: F. Fischer & J. Forester (Eds.), The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (pp. 43-76). Duke University Press.

Hunter, D.J. (2008) Health needs more than health care: The need for a new paradigm. European Journal of Public Health, 18(3), 217-220. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckn039

Ioannidis, M. (2020) Between responsibility and solidarity: Covid19 and the future of the European economic order. Max Planck Institute for Comparative Law and International Law Research Paper Series 2020-39. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3725458

Jabko, N. (2006) Playing the market. Cornell University Press.

Jones, L., & Hameiri, S. (2022) COVID-19 and the failure of the neoliberal regulatory state. Review of International Political Economy, 29(4), 1027-1052. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1892798

Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R.J. (2019) Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 353-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898

Keune, M., & Pochet, P. (2023) The revival of Social Europe: is this time different? Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 29(2), 173-183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258923118505

Krackhardt, D., & Stern, R.N. (1988) Informal networks and organizational crises: An experimental simulation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(2), 123-140. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/2786835

Leifeld, P. (2020) Policy debates and discourse network analysis: A research agenda. Politics and Governance, 8(2), 180-183. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.3249

Leifeld, P. (2017) Discourse network analysis: policy debates as dynamic networks. In: J.N. Victor, M.N. Lubell & A.H. Montgomery (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political networks (pp. 301-326). Oxford University Press.

Leifeld, P. (n.d.) Software. https://www.philipleifeld.com/software/software.html (Accessed 11 August 2025)

Lynch, J. (2023) The political economy of health: Bringing political science in. Annual Review of Political Science, 26, 389-410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-103015

Mittelmark, M.B., & Bauer, G.F. (2017) The meanings of salutogenesis. In: M.B. Mittelmark, S. Sagy, M. Eriksson, G.F. Bauer, J.M. Pelikan, B. Lindström & G.A. Espnes (Eds.), The handbook of salutogenesis (pp. 7-13). Springer Nature.

Nagel, M., & Schäfer, M. (2023) Powerful stories of local climate action: Comparing the evolution of narratives using the ‘narrative rate’ index. Review of Policy Research, 40(6), 1093-1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12545

Quaglia, L., & Verdun, A. (2023) Explaining the response of the ECB to the COVID-19 related economic crisis: inter-crisis and intra-crisis learning. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(4), 635-654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2141300

Ralston, R., Godziewski, C., & Brooks, E. (2023) Reconceptualising the commercial determinants of health: bringing institutions in. BMJ Global Health, 27, 8(11):e013698. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013698

Raworth, K. (2017) Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Random House Business Books.

Rushton, S., & Williams, O.D. (2012) Frames, paradigms and power: Global health policy-making under neoliberalism. Global Society, 26(2), 147-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2012.656266

Schmidt, V. (2008) Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 303-326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

Schmidt, V. (2016) The roots of neo-liberal resilience: Explaining continuity and change in background ideas in Europe’s political economy. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(2), 318-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115612792

Schrecker, T., & Bambra, C. (2015) How politics makes us sick: neoliberal epidemics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, K. (2013) Beyond evidence based policy in public health - The interplay of ideas. Palgrave Macmillan

Smith, M.J. (2008) Re-centring British government: beliefs, traditions and dilemmas in political science. Political Studies Review 6(2), 143-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-9302.2008.00148.x

Spash, C.L. (2021) ‘The economy’ as if people mattered: revisiting critiques of economic growth in a time of crisis. Globalizations, 18(7), 1087-1104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2020.1761612

Steensland, B. (2008) Why do policy frames change? Actor-idea coevolution in debates over welfare reform. Social Forces, 86(3), 1027-1054. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20430786

Tseris, E. (2017) Biomedicine, neoliberalism and the pharmaceuticalisation of society. In B.M.Z. Cohen (Ed.), routledge international handbook of critical mental health (pp.224–233). Routledge.

Wagenaar, H. (2014) Meaning in action: interpretation and dialogue in policy analysis. Routledge.

[1] While individual agential instances are not traceable in the data, we can give the following examples simply to illustrate what this bridge betweenness means in principle: if a policymaker writing mostly about economics connects economics with health ideas, they might cognitively connect those two topics via writing about fiscal stimulus. If a policymaker generally writing about health relates health with economic ideas, they might do so via mentioning health security. This is because ‘fiscal stimulus’ and ‘health security’ are connecting ideas that argumentatively link different clusters. This is illustrated by their big node size in the graph.

[2] It should be noted that EP (Plenary), EP (EMPL), and EP (AGRI) have very few coded statements, their plot may therefore not be representative. ‘EP and Council’ as a sub institution refers to the co-decision legislative procedure for EU Regulations. ‘EC’ under European Commission refers to documents in which a main DG authorship was not specified.

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 3 (2026), Issue 1 CC-BY-NC-ND