Targeting the vulnerable? A critical analysis of helicopter transport for obstetric emergencies in Nepal

Research Article

Jan Brunson1*and Suman Raj Tamrakar2

1Department of Anthropology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, USA 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences, Dhulikhel, Nepal *Corresponding author: Jan Brunson, jbrunson@hawaii.eduIn tandem with national efforts to develop a system of pre-hospital care via ground ambulance services, leading private hospitals in Nepal are competing to institute air ambulances, or helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS). In a nation with limited infrastructure and extreme geography, helicopters offer a high-tech solution to overcoming transportation delays in emergency medicine. Private HEMS, due to the exorbitant costs, invites intersectional analysis along the lines of how wealth, caste or ethnicity, gender, and remoteness shape who is able to utilize it. In contrast, the launch of a governmental program devoted to transporting rural obstetric emergency patients to hospitals, using army helicopters, stands out as an unexpected transformation of a status quo in which only wealthy, elite individuals could access such medical care. Through a review of the trends in maternal mortality and ethnographic field research with doctors in Kathmandu and Kavrepalanchok who are leading the development of emergency medical transport, this paper explores competing interpretations of the driving forces and implications of HEMS, analyzing the benefits and drawbacks to targeting the vulnerable in health interventions.

Introduction

For time-sensitive cases of medical emergencies, rapid transport to a hospital with specialized medical care can make the difference between saving and losing a life – potentially two lives in the case of an obstetric emergency. In places with challenging geography and/or limited infrastructure, transport to a hospital can require a significant amount of pragmatism and ingenuity. Air ambulances, ranging from fixed-wing flights from outer islands in the Hawai‘i archipelago to helicopter flights from rural mountains in Nepal, enable remote residents to overcome the challenges of emergency transport via land or water to a location with adequate medical facilities. Fixed-wing aircraft fly only between airports, but helicopters can transport emergency cases directly from the field to a hospital’s on-site helipad or between two hospitals when specialized care is required (Jones et al. 2018). In this way, helicopter transport is thought to be particularly well suited for certain types of medical emergencies and contexts.

In the case of Nepal, it is easy to understand why helicopter retrieval of individuals experiencing medical emergencies might be necessary. Nepal is home to the highest mountains in the world, and the dramatic change in altitude from the low plains in the south to the Himalaya in the north, along with monsoon rain, present challenges to developing and maintaining adequate road infrastructure. Because of the high cost of helicopter retrieval, however, historically helicopter rescue was associated primarily with the rescue of foreign climbers in Nepal (Maeder et al. 2014). This article is the first to analyze how individuals on multiple fronts are working to transform that history and institute the use of helicopters as emergency medical transport for the Nepali public.

In tandem with national efforts to develop a system of ground ambulance services that include pre-hospital care, leading private hospitals in Nepal are competing to institute air ambulance services, or privately operated helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS). In a nation with such limited infrastructure and extreme geography, helicopters offer a high-tech solution to overcoming transportation delays in reaching emergency medical care. Privately-operated HEMS, due to the exorbitant costs, invite intersectional analysis along the lines of how wealth, caste or ethnicity, gender, and remoteness shape who is able to utilize it. Of course, the development of innovative medical techniques, including helicopter transport, does not guarantee that people will benefit evenly.

In contrast to privately-operated HEMS, the launch of a free governmental program devoted solely to transporting rural obstetric emergency patients to hospitals, using army helicopters, stands out as an unexpected transformation of a status quo in which only wealthy, elite individuals could access such medical care. While this program arguably would be a positive example of targeting the vulnerable, this particular intervention raises the questions of how such a prohibitively expensive venture as helicopter rescue is funded, and why it makes sense for the Nepal Army to be the ones to provide pilots and helicopters. In addition to the government’s helicopter rescue program springing up from a total void of similar services for the vast majority of Nepalis, it also: 1) focuses significant attention on a single subgroup of individuals: rural, pregnant women; and 2) intervenes via dramatic rescue rather than strengthening health systems and infrastructure (which would benefit all emergency patients).

This ethnographic research with doctors and politicians in Kathmandu and Kavre, who are leading the development of emergency medical transport, explores varied expert interpretations of the driving forces and implications of HEMS. In addition to documenting experts’ experiences with: 1) developing a national ambulance system and pre-hospital care; and 2) developing a system of privately operated helicopter emergency medical services; this research 3) formulates (more than it answers) significant questions about the emergent no-cost helicopter rescue program for obstetric emergencies. We frame this research in the context of recent trends in maternal mortality as well as two decades of ethnographic field experience on access to emergency obstetric care in Nepal. The conclusions implicate broader discussions in critical public health by raising previously unexplored benefits and drawbacks to targeting the vulnerable in health interventions.

Conceptual Framework

Structural Violence and Vulnerability

The concept of structural violence has corrected a tendency to blame poor health on an individual and their actions, in a manner that exaggerates the agency of individuals, through identifying the obstacles and constraints individuals face in life (Farmer 1999, Scheper-Hughes 1993). But in locating violence in structures and systems, it becomes difficult to point a finger at a single party or recommend solutions that do not involve overturning entire systems. The more recently developed concept of structural vulnerability purports to be more pragmatic and focus on the individual and the ways they are vulnerable to environmental factors that include symbolic aspects of identity (and their resulting social insults) (Quesada et al. 2011). Structural vulnerability is ‘an individual’s or a population group’s condition of being at risk for negative health outcomes through their interface with socioeconomic, political and cultural/normative hierarchies’ (Bourgois et al. 2017, p. 300, emphasis added). An example from maternal health would be the way that a pregnant person who lacks adequate access to nutritious foods might be anemic, which would, in turn, put them at greater risk in the event of a postpartum hemorrhage. Recent efforts to develop a clinical application of structural vulnerability, which provides healthcare professionals a framework for action in identifying and assisting patients whose health conditions and ‘compliance’ are tied to their social situations, have worked toward transforming social science concepts into praxis (Bourgois et al. 2017). But such applications are tempered by critiques, as they are limited by the discriminatory structures within which they are implemented. In one US example, efforts to provide social services to racialized, low-income pregnant people showed up as increased surveillance and even harassment rather than as assistance (Bridges 2011). In this way, recent scholarship on racism in medicine in the US (see also Wong & Brunson 2025) challenges us to understand the implications of targeting the vulnerable for assistance within the very structures that uphold their domination.

Unintended consequences of targeting the vulnerable on a global scale, within global health initiatives, echo the problems identified thus far – targeting ‘the vulnerable’ or ‘at risk’ within the structures that uphold their domination and further entrenching the essentialization (racialization, classism, etc) and the stigma of those being targeted. The global Safe Motherhood Initiative, for example, despite the improvement in health services for birthing people it has inspired, can also be a structure and set of practices ‘in which systemic racism, classism, and stigma are repeated… against vulnerable and minoritized patient populations’ (Varley & du Plessis 2023, p. 122). Especially when it comes to family planning, global health programs that espouse ideals of empowering women can have unintended negative consequences when they rely on persuasion rather than education (Chatterjee & Riley 2001, Senderowicz 2019, Brunson 2020b). Family planning programs promoting behavioral change (i.e. spacing or reducing births) that target vulnerable groups, such as low-caste and ethnic or religious minorities, can appear paternalistic, at best, and coercive or eugenic at worst (Brunson 2020b, Singh 2020). Programs focused on individual persuasion also fail to address means of achieving structural changes.

Pandhi’s emerging research on structural casteism is of particular relevance to understanding how theories of racism that lead intersectional analyses in the global North articulate in the global South – in this case, South Asia. ‘Like structural racism, casteism thrives on the hierarchical systematization and naturalization of chronic injuries, embodied debilities, racialization, and everyday terrors whose acute excesses are visible among “lower-caste” and Dalit bodies’ (Pandhi 2024, p. 21). Accredited Social Health Activists (local women community health workers) in northern India, while symbolically recognized as global health leaders, still faced structural barriers (caste and gender) that rendered such international recognition ineffective in benefitting their everyday lived experience. In line with Pandhi’s grappling with decolonizing global health, Brunson sought to disrupt ‘a global racialized system of those intervening and those in need of intervention’ (2021, p. 138) through the stories of Nepali women People’s Liberation Army ex-combatants’ procreation during a protracted civil war and its aftermath. Nepali women’s struggles to achieve a more equitable society, in terms of caste, gender and wealth, when they take the form of fighting in a revolution, upset global health and development narratives that continue to rely on portraying women in the global South on the passive, receiving end of intervention in their health, economic, and reproductive lives.

Analyzing such intersectionality (Collins & Bilge 2020) and its impact on health is critical to understanding the complex ways in which people may be vulnerable, as well as the unintended consequences of targeting the vulnerable. Here, we document and analyze the development of emergency medical transportation programs in Nepal with attention to who is being targeted, why, and what is at stake.

Targeting and Emergency Obstetric Care

Maternal health, like other global health issues, has been addressed both through programs that focus on horizontal, or primary health, improvements that include meeting basic needs and providing primary health care, and by programmatic interventions that are more vertical in nature, such as providing contraception. Vertical interventions arguably are less impactful in maternal health, however, because maternal health is notorious for being linked to fundamental categories of equity, such as less social disparity in gender, class, ethnicity, and education. No quick fix is possible in the case of maternal mortality; there is no vaccine or cure. And because obstetric emergencies are difficult to predict, maternal mortality is a good general indicator of whether an adequate health system exists. So, while a debate over horizontal versus vertical methods in maternal health has not been as pronounced historically as in the case of contagious diseases (Farmer et al. 2013), the history of maternal health programs and interventions helps explain how medical transport has become a programmatic focus.

With the launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) in 1987 by the Safe Motherhood Conference in Nairobi, maternal health began to be constructed, categorized, and labelled as a global health indicator. The initial goals of the SMI included investments in primary health tactics, addressing root causes of maternal health and reflecting the values of the Alma Ata international conference on primary health care. But after initial investments in local cadres of health workers did not result in lowered maternal mortality, program emphasis shifted from holistic approaches to technological fixes and access to emergency obstetric care (EmOC) (Varley & du Plessis 2023). ‘This move away from the SMI’s original holistic approach led to institutional over-attention to EmOC as a solution, disregarding historical case studies confirming that the solution to maternal mortality lies in broader societal change. These then correlated with subsequent inattention within SMI to the ‘social and political determinants of maternal health, which precede crises’ (Varley & du Plessis 2023, p. 123). And despite the rhetoric of integration and partnership involved when 80 organizations joined forces under the Partnership in Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) in 2005, in practice, structural and political drivers continued to bias the global health field toward vertical interventions (Storeng & Béhague 2016).

While objections have been raised about an overemphasis on emergency obstetric care, and the way this constitutes a narrow (Storing & Béhague 2016) or perhaps a vertical intervention in maternal health, a portion of the maternal morality ratio (MMR) would remain stubbornly unchanged if pregnant people did not have access to specialized obstetric care in the event of birth emergencies at home or at health posts. A focus on transport in global health thus arose with the move toward providing emergency obstetric care. Referral systems were one solution posed in low-income countries. Low-risk births are handled at the local level, and difficult cases are referred to a hospital (Murray & Pearson 2006). Universal hospital delivery was another suggestion, along with maternity waiting homes for pregnant people who lived too far from a hospital, but a variety of objections arose from anthropologists working with Indigenous and other marginalized groups who were disrespected in medical institutions (Berry 2010, Smith-Oka 2013). It is with this history of debates within global health about lowering maternal mortality that this paper addresses the problem of transport to hospitals in Nepal.

We bring these genealogies to a study of vulnerability in the context of reproductive health in Nepal. We tell a story of the absence of pre-hospital care in ground and air ambulances, the development of a nascent private system of helicopter emergency medical services, efforts to develop a national system of pre-hospital care, and an exceptional governmental helicopter rescue program that targets obstetric emergency patients in remote areas. It is a contradictory story of absence and priority, and how the two exist in an uneasy relationship.

Methods

The objectives of this exploratory research on helicopter emergency medical services in Nepal required three field research components, with each involving ambitious recruitment of experts, lengthy interviews, and participant observation in offices, vehicles, and homes. This draws on research by Author 1 (Brunson), who conducted three weeks of in-person ethnographic interviews and participant observation in March 2023 with a total of eight experts spanning two districts, Kathmandu District and Kavrepalanchok District. In sum, this comprised eleven interviews, with interviews ranging from one to three hours each. Interviews often included eating a meal in someone’s home, or drinking coffee in a restaurant, in addition to sitting in offices. The research received IRB human subjects approval by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. The following descriptions, in first person, detail the three components.

1. The Ongoing Development of Ground Ambulance Services and Prehospital Care

The interviews and participant observation for this component took place at two leading hospitals, which will be named Urban Private Hospital and Rural Public Hospital. At Urban Private Hospital, I interviewed a leading emergency medicine doctor three times, an emergency medicine staff member once, and was given a comprehensive tour of the hospital’s new ground ambulance, with permanently stocked shelves of medical supplies. At Rural Public Hospital, I interviewed the head of department (obstetrics), who then facilitated the introductions to the department of emergency medicine. I interviewed a leading doctor in emergency medicine, who was a developer of the national curriculum in pre-hospital care, and the trauma coordinator, who had a particular interest in developing HEMS.

2. The Ongoing Development of Privately-Operated Helicopter Emergency Medical Services

The interviews and participant observation for this component overlaps with what is described above for Urban Private Hospital. In addition, I toured the hospital office containing all of the mobile medical supplies, in compartmentalized go-bags or on wheels, for use in private helicopter emergency medical transport. The emergency medicine doctor at Urban Private Hospital also facilitated a meeting and interview with one of Nepal’s first helicopter pilots. I am grateful to the Captain’s family for entertaining us at their family compound with such generosity and facilitating our discussion of the history of helicopters in Nepal.

3. The Introduction of a Governmental Helicopter Rescue Program for Obstetric Emergencies

This component involved networking and locating individuals who could speak with authority about the development of the governmental helicopter rescue program. This proved to be the area for which it was most difficult to recruit interviewees. After much help from local friends, I was granted interviews with a government employee and a political advisor to the President. Both were conducted publicly in restaurants. A further attempt to meet with a third expert was cancelled by historic flooding in the fall of 2025 that shut down transportation.

By investigating these three components, we attempted to piece together a picture of the development of pre-hospital care, of HEMS, and of a nascent helicopter rescue program that has the potential to transform access to care during obstetric emergencies in Nepal.

Results and Discussion

Developing Ground Ambulance Services and Prehospital Care

In 2020, Nepal rose from being categorized as a low-income country to a lower-middle income country, according to World Bank classifications based on gross national income (Serajuddin & Hamadeh 2020). It has remained in that category since. This change in classification belies the vast disparities in incomes and access to health services between elite, urban families and remote, disenfranchised ones. A few brief vignettes from past field research in Nepal provide context.

In an interview in 2004 with a middle-aged Nepali mother who lived in the rural outskirts of Kathmandu, not far below one of the ridges that outline the Kathmandu Valley, she taught me (Brunson) how large baskets carried on one’s back, dhoko, used for carrying fodder or fertilizer (or basically anything–sand, bricks), could be used to carry a person in an emergency. She recollected how, in the 1980s, she had been carried in a dhoko down a path to reach the nearest road during an obstetric emergency (Brunson 2016, 2018).

Later in 2015, while conducting research in the aftermath of the earthquakes, young couples explained that although paved roads had reached new heights throughout the area, the last stretch between the road and their ‘temporary’ corrugated galvanized iron houses required a steep climb on foot. In these Tamang settlements north of Kathmandu that had been badly damaged, young men with powerful off-road motorbikes pointed out that even their motorbikes couldn’t handle the steep footpath that connected to the narrow dirt road below. In medical emergencies, they had to carry people down to where a motorbike waited (Brunson 2017).

In January of 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic, a photo circulated on social media that provides another example of low-tech medical transport in a rural setting. Leela Thapa, a Female Community Health Volunteer (FCHV), was portrayed carrying a 78-year-old woman on her back along a mountain path to a COVID-19 vaccination clinic. The image, and the polarized responses to it, went viral on social media, as viewers debated whether it was a story of a healthcare hero or evidence of an inadequate healthcare system. When I viewed this image, I saw the familiar sky-blue sari that easily identified Ms. Thapa as a Female Community Health Volunteer. I saw a woman accustomed to carrying, unlike many younger people in more urban areas who actively disassociate themselves from agriculture, labor, and carrying as a matter of pride (see also Pigg 1992 on carrying). I recalled an entertaining, aged mother-in-law with a lifetime of agricultural work joking about how women can’t walk quickly wearing sari, shuffling her feet for comedic effect in miniature steps as if constrained by a sari. When I viewed this image, I wondered where the young, male family members were, why a woman volunteer was doing this carrying, and pondered the feminization of rural areas as men migrate to urban areas for income.

From a practical point of view, the photo of the volunteer looks like the type of pragmatism one is accustomed to in rural and semi-urban parts of central Nepal. And the use of a modified dhoko, or nowadays an improvised stretcher, seems like an adaptive technology for medical transport. These examples of pragmatism, of low-tech solutions, demonstrate determination and ingenuity, but also an insufficient infrastructure and health system.

The vast majority of Intensive Care Unit capacity in Nepal is concentrated in the capital, Kathmandu (Aryal 2016, Acharya 2013, Neupane et al. 2020). And prehospital care–receiving medical care in an ambulance during transport–is in its infancy in Nepal (Karki et al. 2022). In the past, ground ambulances were not much more than a taxi. There were no EMTs (Emergency Medical Technicians) in the ambulances, nor were there any medical supplies. In research from the outskirts of the Kathmandu Valley in 2003-5, I (Brunson) discovered that people did not typically call an ambulance for this reason during obstetric emergencies. Moreover, there often was a taxi already present nearby, as opposed to an ambulance located at a hospital that would take extra time to reach them.

Nepal does not have a nationally integrated Emergency Medical Services (EMS) system (Bhandari & Yadav 2020), and ground ambulances are run by private companies. However, in 2011, the National Ambulance Service was established along with a program that encourages families to ‘Call 102’ instead of a taxi in the event of a medical emergency (Shrestha et al. 2018). Dr. Shrestha explained how, since 2008, he had been grappling with how to start a coordinated system of ambulance services that offered prehospital care:

Here, since 2008 in this hospital, many people arrive late stage, when their condition is very bad. There are delays due to transportation, and no medical care on the way. Some die simply due to lack of [administering] oxygen. The [taxi] driver can stop to take tea on the way, and the patient dies from heart attack or bleeding. After observing this, we knew we must start [an ambulance service].

At one point in the conversation, he disparagingly referenced the dhoko as emergency transport, saying that we must figure out ‘how to make the services available so [people are] not using dhoko’. The National Ambulance Service currently serves Kathmandu and Patan only, but they plan to extend their services nationwide. An obvious challenge to this, however, is Nepal’s limited road infrastructure.

In Nepal and similar countries that have limited road infrastructure, living in a remote area impacts what services and goods are available and, concomitantly, shapes one’s identity. Thus, along with gender, caste, and class, we argue that ‘remote’ has to be part of intersectional accounting. Since access to emergency medicine (not limited to emergency obstetric care) relies upon transport, emergency medicine doctors in Nepal have been pushing for greater awareness and prioritization of transport in recent years (Brunson 2024). Dr. Shreshta expressed dissatisfaction with the ways coordinated pre-hospital care had been neglected up until that point, with people dying unnecessarily before ever reaching the hospital. Searching his bookshelf for a copy of the emergency medical dispatcher training manual he helped author on the topic (see Jacobson et al. 2021), he pointed out that financial support always goes to hospitals and not transport. His target for the future is that adequate prehospital care–whether via ground ambulance or helicopter–should be available to all, not just the rich. The trauma coordinator, Mr. Parajuli, added later, ‘To bring in the golden hour, a helicopter is needed’.

Developing Privately-Operated Helicopter Emergency Medical Services

Helicopter emergency services in Nepal historically have been associated with elite, foreign climbers who needed rescue due to altitude sickness or accidents (Maeder et al. 2014). They were rarely used for Nepalis. In 2018, during field observations at Rural Public Hospital, the story of a family chartering a private helicopter for a woman undergoing an obstetric emergency caught Brunson’s attention, as it indicated that an expansion of the service and its usage was underway. Most significant was the fact that it was chartered for an obstetric emergency, something that had not warranted calling a ground ambulance in my previous research on obstetric emergencies in a semi-urban location. The use of helicopters in responding to the 2015 earthquakes and the adaptation of helicopters for transporting COVID-19 patients during the pandemic broadened their perceived application.

In order to address pressing needs for emergency medical transport, especially from rural facilities, Dr. Sanjaya Karki has been working in the private medical sector to develop a system of helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) that includes prehospital care for emergency cases needing transport to a better-equipped hospital. He first helped establish HEMS at Grande Hospital in 2013, later shifting to Urban Private Hospital when it opened in 2017. The four hospitals in Kathmandu that currently offer helicopter emergency medical services are Mediciti Hospital, Grande International Hospital, Vayodha Hospital, and HAMS Hospital—all private hospitals.

Private hospitals, Dr. Karki explained, utilize the same commercial helicopters and pilots as tourists, rather than a dedicated helicopter for medical transport. When the hospital receives a request for a helicopter, they contact the airport to find out which company has an available helicopter. Then they connect the individuals directly with the private helicopter company to charter a helicopter and pilot. In this way, the hospital remains uninvolved in the potentially complex financial negotiations for the helicopter service. The patient or family member also must choose whether they are willing to pay for a doctor or EMT to be present in the helicopter. Dr. Karki emphasized that 99% of the patients he transfers via helicopter are from one ICU to another ICU, not from the scene of the emergency.

Since there are no helicopters dedicated solely to emergency medical services (see also Karki et al. 2022), the medical supplies must be portable. Mr. Neupane showed Brunson how they are kept in go-bags, basically hefty backpacks that can unfold to reveal clear internal compartments. Next to the shelves of go-bags, tall oxygen canisters waited on wheels. Dr. Karki described how the helicopter has to be retrofitted to meet the space and equipment needs of patients and pilots each time (see also Karki & Sprinkle 2021). Since in Nepal there is no requirement for a copilot, the copilot seat can be removed to make room for a stretcher, and one of the seats in the rear is removed to accommodate a monitor and oxygen tank.

Developing a national system of HEMS that is no longer used almost exclusively for rescuing climbers is a positive development in terms of building health systems capacity. In high tourist season, however, Brunson was told it can be difficult to charter a private helicopter for medical purposes because of the competition for mountain viewing flights. Another limitation, Dr. Karki reported, is that private helicopters can only fly from sunrise to sunset. For example, if he receives a call from Biratnagar at 3:00 p.m., and flight time from Kathmandu is around one hour, it will be difficult to manage. Poor weather conditions, such as fog, monsoon rains, and wind also limit flights. But the greatest limitation of HEMS is its expense, which will exclude the majority of the population from utilizing it–especially those living at a greater distance from Kathmandu. Putting these limitations into perspective in terms of his achievements, Dr. Karki concluded, ‘My main target is to develop the service. At least then the service can be obtained.’

Governmental Helicopter Rescue Program for Obstetric Emergencies

The absence of prehospital care, a national system of ground ambulances, and HEMS was what made the appearance of the government helicopter rescue program specifically aimed at obstetric emergencies seem so exceptional and unexpected. In 2018, the Office of the President started an innovative program that employs army helicopters to serve on rescue missions for rural women experiencing obstetric emergencies, called the President’s Program for the Upliftment of Women. This is a significant development in terms of national policy and budget, and begs the question of how using helicopters and limited public health funds to save mothers’ lives became such a high national priority.

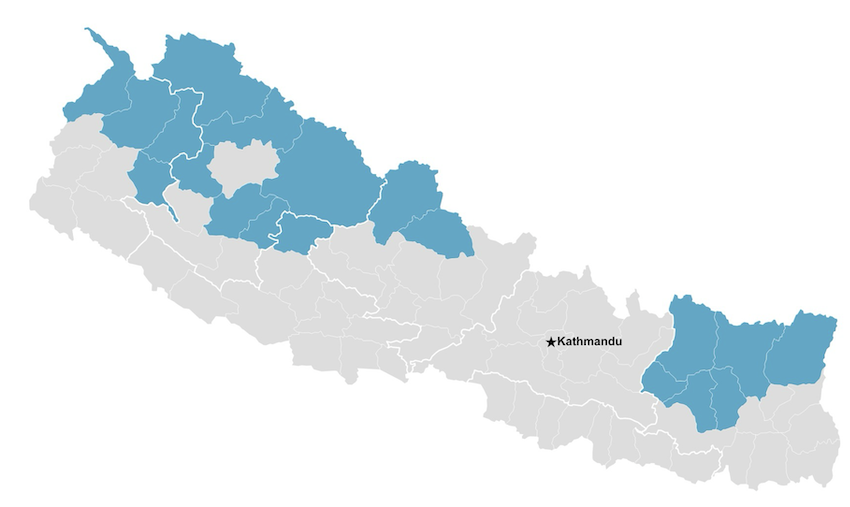

The government initiated a helicopter rescue service that specifically targets women experiencing obstetric emergencies in isolated areas that do not have an adequate road system and/or are too distant from a hospital. A government employee shared a document in Nepali that listed the nineteen districts that were selected to participate in the program, from which Brunson created a map with the locations of the nineteen districts (see Figure 1). The selected districts correspond with the swath of mountainous areas of the Himalaya in the north. Bagmati Province is excluded from the program because the numerous hospitals in Kathmandu and one in Dhulikhel adequately serve this area. Moreover, a major international road has been constructed that runs north and south in this district, making road travel dependable.

The governmental helicopter rescue program is distinct from private HEMS in almost every way. It is operated using Nepal Army helicopter pilots and helicopters. It is free of charge for the patient. It only serves women in obstetric emergencies–no other emergency cases. The program functions as a rescue program, sending helicopters to isolated areas that often do not have landing pads, to retrieve women (and their newborns) experiencing life-threatening, birth-related emergencies. In contrast, private HEMS do not perform rescues; rather, they transport a patient from one medical facility to another better-equipped private hospital to administer the emergency care. The army helicopters typically take women to the Kathmandu airport, from where they are transported by ground ambulance to the government maternity hospital (unlike private chartered helicopters that take patients directly to a private hospital’s helipad). This extra step, and the added difficulty of navigating road traffic, has been pointed out by critics. Overall, though, the program remains an impressive investment in mitigating maternal mortality.

Figure 1. Nineteen Districts of Nepal covered by the President’s Program for the Upliftment of Women in 2024

In the 19 qualifying districts, local village healthcare workers identify birthing people at risk and notify a triage team at the province level, who arrange the helicopter dispatch and retrieval of the woman to the closest government hospital offering emergency care (Sharma et al. 2024). After receiving treatment, funding is provided to the woman and her escort to return by ground transportation to their home village. As of March 2024, a total of 659 birthing women had been rescued by helicopter as part of the President’s Program for the Upliftment of Women (Anon 2024).

But how did this impressive mobilization of political will and government funds targeting maternal survival come to manifest? It might be an effort to overcome a stagnating decline in maternal mortality to meet the Sustainable Development Goals – a high-tech fix to gendered health inequities and intractable upstream causes. In terms of emergency obstetric care, a report on the Nepal Health Facility Survey 2021 indicated that women in Nepal were experiencing delays primarily in arrival at a health facility (Riese & Dhakal 2023), which is known as the second delay in the classic three delays model (Thaddeus & Maine 1994). Perhaps whether the program is interpreted as a stopgap measure or an integral part of the national healthcare system depends on how long it lasts.

Overall, Nepal has experienced a decline in MMR since 1996. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) serves as the major metric in assessing maternal health around the world, despite objections and caveats to using MMR as an accurate measurement (Wendland 2016, Storeng & Béhague 2017, Brunson & Suh 2020) and calls for a focus on improving maternal health rather than only averting death (Brunson 2020a). The global reliance on this metric is bolstered by its recognition as part of the Millennium Development Goals and now the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG Target 3.1 aims to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births.

Nepal was celebrated for making significant progress in reducing the MMR from 539 in 1996 to 281 in 2006 (Hussein et al. 2011, Shrestha et al. 2014). In the following period, the decline stalled, dropping to only 239 by 2016. This ‘stagnation’ was addressed by a study that interviewed key informants in the maternal health sector in Nepal. The results indicate that while the maternal health experts thought policies were adequate, implementation was ineffective and strategies needed to be tailored to the local context. Poor quality of care was also identified as an issue along with inaccessibility of facilities offering comprehensive emergency obstetric care (Karkee et al. 2021). In sum, the experts in the maternal health sector did not recommend new programs, simply better follow through on the ones in place.

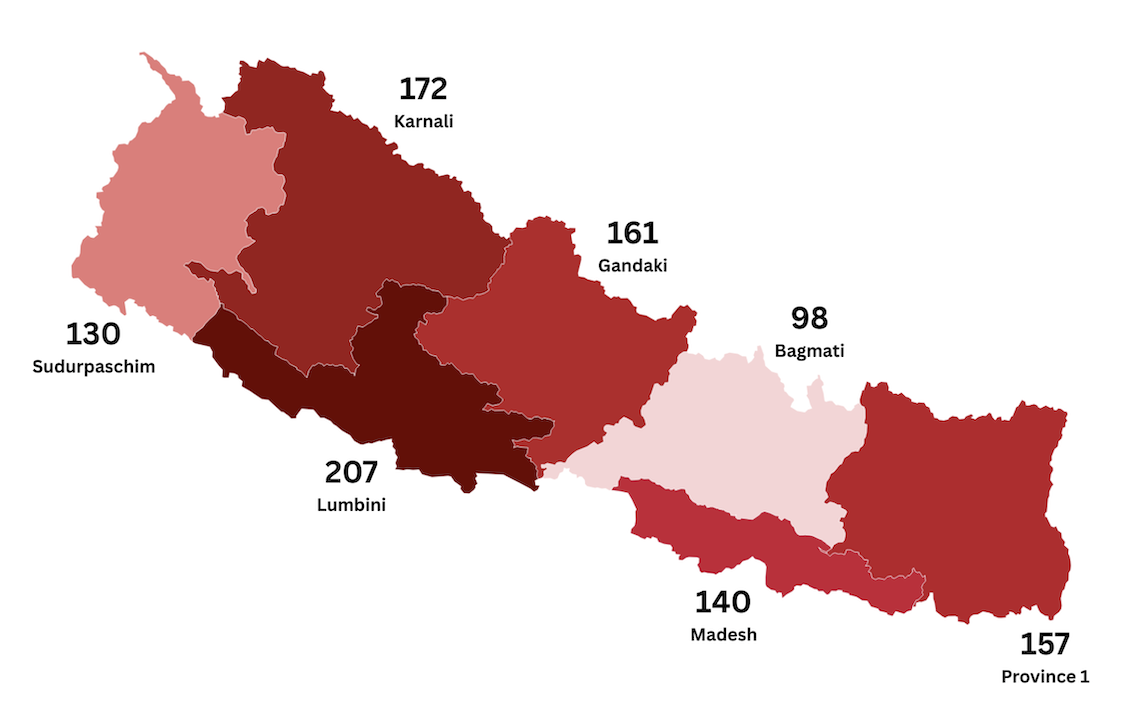

Following that stall in decline, Nepal’s MMR decreased more notably to 151 in 2021, according to the Nepal Census (Ministry of Health and Population 2022). Nepal included questions on maternal deaths for the first time in the 2021 census, even breaking down the MMR by province (see Figure 2). Not surprisingly, the province that includes the sprawling capital city of Kathmandu, Bagmati, was reported to have the lowest MMR, 98.

Figure 2. Nepal Maternal Mortality Ratio (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) by Province. Sources of data: National Population and Housing Census 2021: Nepal Maternal Mortality Study 2021, p. 27

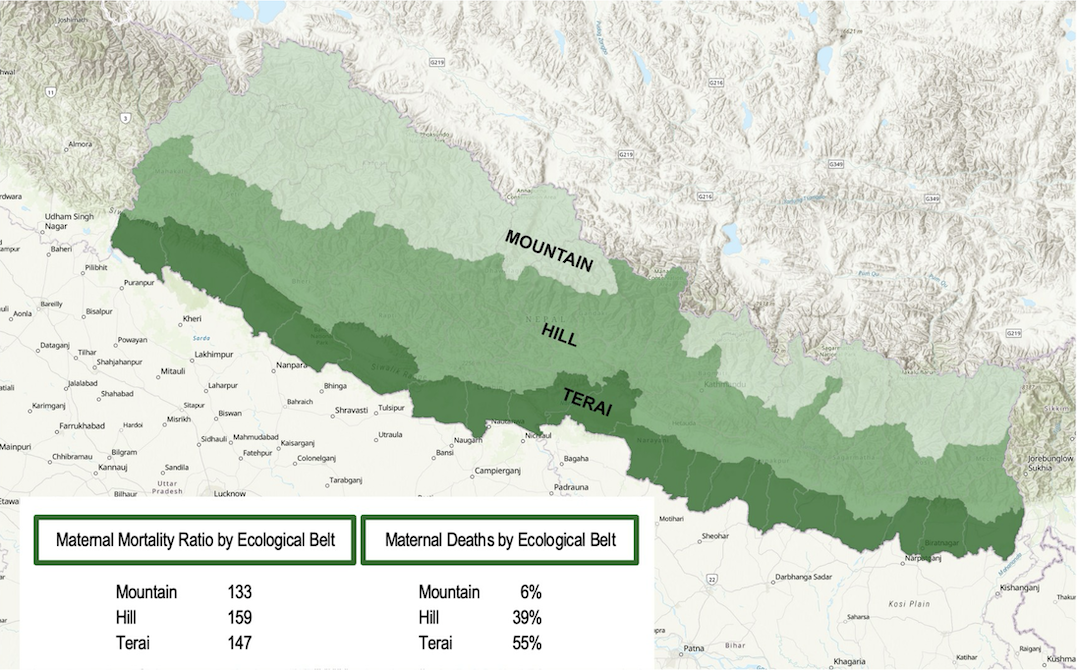

Figure 3. Nepal Maternal Deaths by Ecological Zone. Source of data: National Population and Housing Census 2021: Nepal Maternal Mortality Study 2021, p. 12

Since the utilization of helicopter rescue is in response to the challenging terrain of the Himalaya, it is instructive to consider maternal mortality data in relation to ecological zones, as well. Additional data from the Nepal Maternal Mortality Study 2021 show that in terms of simply enumerating deaths, 55% of maternal deaths occurred in the low, flat plains of the Terai (see Figure 3). The Terai region has a relatively dense population, and thus more total births and chances for a maternal death, in comparison to the Hill and Mountain regions. Comparing the maternal mortality ratios and the percentage of maternal deaths in the three regions side-by-side, as in Figure 3, raises interesting questions about calculating death and measuring risk.

Thus far, interviewees have told Brunson that the development of the helicopter rescue program is a result of Bhidya Bhandari being Nepal’s first woman President and her prior experience traveling to remote areas of Nepal, observing firsthand the conditions women faced. According to one of her former advisors, after she was elected President, Bhidya Bhandari was considering how to address gender issues, and she initiated a series of meetings with women activists, experts, and media persons involved in gender issues. In consultation with health-related stakeholders, she and her team designed the program, President’s Upliftment of Women. The helicopter rescue program developed under this broader program, which included providing economic empowerment for women’s cooperatives. President Bhandari met with a doctor who worked at the Department of Health for recommendations. The program was fully funded by the Nepal Government and did not rely on outside funding. Her former advisor and a current government official assured me that the initiative would not end when her presidency ended in 2023, and at the time of publication the program was still active.

Another source, a 2024 report, revealed that Ministry of Social Development and Health Secretary for Gandaki Province, Dr. Binod Bindu Sharma, played a prominent role in the program’s development. In 2017-2018 while earning his Ph.D. at the University of Newcastle, Australia, he met with leaders at the Ministry of Health to discuss the need for helicopter rescue for remote obstetric emergencies in order to decrease the number of maternal deaths. The Ministry forwarded the proposal for the program as a special initiative. A team from the University of Newcastle met with a delegation from Gandaki Province and a delegation of women Parliamentarians, and their discussions led to the implementation of the program. Nepal’s President inaugurated the program as a special initiative under the Presidential Women’s Development and Empowerment Program (Sharma et al. 2024).

In Gandaki Province, which abuts Bagmati Province to the west, Dr. Sharma reported that the provincial government is working toward the building and upkeep of helipads in all 85 municipalities. The program, at least as he described it in Gandaki, does not have the appearance of a stopgap measure; rather, he emphasized that the saving of mothers’ lives must be by design–through a well-planned program, effective communication, and coordination, which include helicopter rescue as part of health systems strengthening (Sharma et al. 2024).

Conclusions

The title of the article, Targeting the Vulnerable, suggests that both of these global public health terms have a role to play in interpreting the development of HEMS for obstetric emergencies in Nepal. First, what is at stake in being labeled vulnerable or in locating vulnerability in a body, as opposed to naming and locating the external social and environmental forces that impact bodies and constrain their actions? And second, in what way is targeting a means of prioritizing, responding to perceived deservingness or needed reparation, and when might it be a form of vertical intervention that does little to meet basic needs or address underlying structures of inequality?

In many ways, the preliminary conclusions fall along the lines familiar to us via the literature on social justice and health: the existence of medical services does not equate to access to them, nor does it result in equal treatment and care. Investigating private helicopter emergency medical services, due to its exorbitant costs, offers an avenue to explore how wealth, caste, gender, and remoteness may shape who utilizes air ambulances and who is excluded. And further investigating the new President’s Program–the history of its support and implementation–could reveal how political will and funding can be mobilized toward particular global health goals. The program has the potential to address what several experts noted about the private services–they were only available to the wealthy or those willing to sell their land (i.e. spend their entire inheritance) to pay for medical costs.

In general, almost everyone interviewed, from emergency medicine doctors to EMTs to government officials and politicians, acknowledged that helicopter emergency services are costly and difficult to sustain without major subsidies or the payments of wealthy users. They recognized that national investments in rural health systems and staffing were necessary for the long term. So, much like the opening image of the Female Community Health Volunteer carrying an elderly person on her back, remote helicopter rescues, in some respects, were viewed as a temporary but much-needed solution to a health systems problem. That said, people like Dr. Karki are working toward integrating helicopter medical services effectively into a well-functioning national health system, as well.

One of the key distinctions of the governmental helicopter obstetric emergency rescue program–the role of the army–may turn out to be precisely what makes the program become a long-term solution. Repurposing military helicopters for medical rescue does not require expensive investment in new vehicles. The rescue flights also provide army pilots with ongoing flight training. The urgency of the missions and the challenging and unpredictable conditions, such as weather, unfamiliar terrain, and lack of landing pads, simulate conditions one would also encounter during war or disaster. Furthermore, participation in the program ensures regular checks and maintenance of the helicopters.

Difficult ground terrain can lead to the sky becoming the imagined space in which to overcome it, but helicopter transport comes with its own limitations and risks. Nighttime flights are highly risky, for example, and they are not possible at all for private helicopters because they lack night vision. Calls for transport that come too late in the day cannot be responded to until the following morning due to the calculation of the total time necessary for a roundtrip flight and the limitation of nightfall. In Brunson’s interview with Captain Rabindra Pradhan, renowned for being one of Nepal’s first helicopter pilots and the leader of historic helicopter rescue efforts, he astutely suggested that helicopters should be located at strategic points throughout the country to cut down on the amount of time it takes the helicopter to reach the patient. Perhaps this might be more easily accomplished in the case of army participation, because a small number of remote bases could house a helicopter. It would be much less likely to happen in the private sector, since a commercial pilot would not want to base their helicopter in areas that have very little demand for services.

In terms of the President’s Program for the Upliftment of Women, areas for future research include the following questions. Is access to the service at the village level constrained by subtle casteism or other existing systems of privilege and discrimination? What is the impact of the high visibility of the rescue program in remote villages? If the government values women’s health so much that it targets obstetric patients for what would otherwise be a service available only to the elite, has this improved the way villagers view the value of women’s health? Has it created any backlash or jealousy by those whose medical emergencies do not qualify?

Also in need of future research are the experiences of women who participated in the program. The novelty and the overall sensory experience of traveling via helicopter generates stress, particularly the noise. In addition, in the shadow of the People’s War, in which many rural villagers either participated in the People’s Liberation Army’s fight against the Nepal Army, were coerced into housing the PLA members, or were interrogated by the Nepal Army as having done one of the two, being picked up by a Nepal Army helicopter and an army pilot in uniform has the potential to create stress for women and couples. Contrast this with the efforts to make medical helicopters in the United States more appealing and less mechanical to children and their parents, such as a dedicated helicopter called Monarch I painted with pastel butterflies (R. Tjoeng, personal communication). The militarization of care in Nepal deserves further analysis.

In conclusion, this novel program, the President’s Program for the Upliftment of Women, warrants further analysis along multiple lines, including the ways it targets the vulnerable and the potential for unintended consequences. While at the outset the program may appear as a vertical intervention to reduce maternal mortality, the mutual benefits the program provides for the maternal health system and the Nepal Army have potential to transform it into a stable part of strengthening infrastructure and health systems. The program also provides an example of the way notions of ‘the vulnerable,’ irrespective of their paternalism, can be leveraged in predictable and positive ways–effectively capitalizing on gendered notions of vulnerability. However, this rather dramatic technological and political solution should not be allowed to distract from also addressing the structural drivers of maternal mortality and efforts to decolonize paternalistic tropes in public health.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented in the 2023 Seminar of the Fertility and Reproduction Studies Group, Oxford University, on Fertility and Vulnerability. The authors would like to express gratitude to the organizers of that event and the subsequent special issue of which this article is a part, with special thanks to Kaveri Qureshi for her insightful editorial feedback at multiple stages. Thanks are also due to Dhirendra Nalbo and Manoj K. Shrestha for graciously providing introductions. And last, we thank the medical and political experts – named and anonymous – who shared their experiences.

ORCiD IDs

Jan Brunson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9808-1165

Suman Raj Tamrakar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4735-6851

References

Acharya, S. P. (2013) Critical care medicine in Nepal: Where are we? International Health, 5(2), 92-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/iht010

Anon (2024, March 13th) Air rescue of 659 pregnant women and children. Khabarhub. https://khabarhub.com/2024/13/605908/

Aryal, B. P. (2016, Dec 31st) Critical health care centralized in capital. My República. Critical health care centralized in capital - myRepublica - The New York Times Partner, Latest news of Nepal in English, Latest News Articles | Republica

Berry, N. (2010) Unsafe motherhood: Mayan maternal mortality and subjectivity in post-war Guatemala. Berghan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3167/9781845457525

Bhandari, D., & Yadav, N. K. (2020) Developing an integrated emergency medical services in a low-income country like Nepal: A concept paper. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-0268-1

Bourgois, P., Holmes, S. M., Sue, K., & Quesada, J. (2017) Structural vulnerability: Operationalizing the concept to address health disparities in clinical care. Academic Medicine, 92(3), 299-307. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001294

Bridges, K. (2011) Reproducing race: An ethnography of pregnancy as a site of racialization. University of California Press.

Brunson, J. (2016) Planning families in Nepal: Global and local projects of reproduction. Rutgers University Press.

Brunson, J. (2017) Maternal, newborn, and child health after the 2015 Nepal earthquakes: An investigation of the long-term gendered impacts of disasters. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 21, 2267–2273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2350-8

Brunson, J. (2018) Maternal health in Nepal and other low-income countries: Causes, contexts, and future directions. In N. Riley & J. Brunson (Eds.), International handbook on gender and demographic processes (pp. 141-152). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1290-1_10

Brunson, J. (2020a) Concealed pregnancies and protected postpartum periods: Defining critical periods of maternal health in Nepal. In V. Petit, K. Qureshi, Y. Charbit, & P. Kreager (Eds.), The anthropological demography of health (pp. 472-492). Oxford University Press.

Brunson, J. (2020b) Tool of economic development, metric of global health: Promoting planned families and economized life in Nepal. Social Science & Medicine, 254, 112298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.003

Brunson, J. (2021) Reproduction through revolution: Maoist women’s struggle for equity in post-development Nepal. In S. Han & C. Tomori (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of anthropology and reproduction (pp. 137-149). Routledge.

Brunson, J. (2024) The golden hour. HIMALAYA, 43(2), 35-37. https://doi.org/10.2218/himalaya.2024.9106

Brunson, J., & Suh, S. (2020) Behind the measures of maternal and reproductive health: Ethnographic accounts of inventory and intervention. Social Science & Medicine, 254, 112730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112730

Chatterjee, N., & Riley, N. E. (2001) Planning an Indian modernity: The gendered politics of fertility control. Signs, 26(3), 811-845. https://doi.org/10.1086/495629

Collins, P., & Bilge, S. (2020) Intersectionality (2nd ed.). Polity.

Farmer, P. (1999) Infections and inequalities: The modern plagues. University of California Press.

Farmer, P., Kleinman, A., Kim, J., & Basilico, M. (2013) Reimagining global health. University of California Press.

Hussein, J., Bell, J., Dar Iang, M., Mesko, N., Amery, J., & Graham, W. (2011) An appraisal of the maternal mortality decline in Nepal. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19898. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019898

Jacobson, C., Basnet, S., Bhatt, A. (2021) Emergency medical dispatcher training as a strategy to improve pre-hospital care in low- and middle-income countries: The case study of Nepal. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14(28) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-021-00355-8

Jones, A., Donald, M. J., & Jansen, J. O. (2018) Evaluation of the provision of helicopter emergency medical services in Europe. Emergency Medicine Journal, 35(12), 720-725. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2018-207553

Karkee, R., Tumbahanghe, K. M., Morgan, A., Maharjan, N., Budhathoki, B., & Manandhar, D. S. (2022) Policies and actions to reduce maternal mortality in Nepal: Perspectives of key informants. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29(2), 1907026. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1907026

Karki, S., Singh, S., Malla, D. K., Basnet, Y., Chaudhary, V., Neupane, E., Bhandari, R., & Adhikary, A. (2022) System of helicopter emergency medical services in Nepal: A study at Nepal Mediciti Hospital. Air Medical Journal, 41(1), 37-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amj.2021.09.009

Karki, S., & Sprinkle, D.J. (2021) Helicopter emergency medical services during Coronavirus disease 2019 in Nepal. Air Medical Journal, 40(4), 287-288. https://doi:10.1016/j.amj.2021.04.005

Maeder, M. M., Basnyat, B., & Harris, N. S. (2014) From Matterhorn to Mt Everest: Empowering rescuers and improving medical care in Nepal. Wilderness Environmental Medicine, 25(2), 177-81. https://doi:10.1016/j.wem.2013.12.029

Ministry of Health and Population & National Statistics Office (2022) National Population and Housing Census 2021: Nepal Maternal Mortality Study 2021. Ministry of Health and Population & National Statistics Office.

Murray, S. F., & Pearson, S. C. (2006) Maternity referral systems in developing countries: Current knowledge and future research needs. Social Science & Medicine, 62(9), 2205-2215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.025

Neupane, H.C., Gauli, B., Adhikari, S., & Shrestha, N. (2020) Contextualizing critical care medicine in the face of Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Nepal Medical Association, 58(226), 447-452. https://doi:10.31729/jnma.5153

Pandhi, N. (2024) The ‘caste’ of decolonization: Structural casteism, public health praxis, and radical accountability in contemporary India. In T. Masvawure and E. Foley (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of anthropology and global health (Vol. 1, pp. 19–34). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003284345-3

Pigg, S. L. (1992) Inventing social categories through place: Social representations and development in Nepal. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 34(3), 491-513.

Quesada, J., Hart, L. K., & Bourgois, P. (2011) Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology, 30(4), 339-362. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.576725

Riese, S., & Dhakal, R. (2023) Understanding the three delays among postpartum women in Nepal. DHS Further Analysis Report No. 144. ICF.

Scheper-Hughes, N. (1993) Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. University of California Press.

Senderowicz, L. (2019) ‘I was obligated to accept’: A qualitative exploration of contraceptive coercion. Social Science & Medicine, 239, 112531. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112531

Serajuddin, U., & Hamadeh, N. (2020) New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2020-2021. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2020-2021.

Singh, H. D. (2020) Numbering others: Religious demography, identity, and fertility management experiences in contemporary India. Social Science & Medicine, 254, 112534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112534

Sharma, B. B., Pennell, C., Sharma, B., & Smith, R. (2024) Reducing maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries: The Nepalese approach of helicopter retrieval. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 230(5), 473-475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.01.026

Shrestha, S., Bell, J. S., & Marais, D. (2014) An analysis of factors linked to the decline in maternal mortality in Nepal. PLOS ONE, 9(4), e93029. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093029

Shrestha, S. K., Koirala, K., & Amatya, B. (2018) Patient’s mode of transportation presented in the emergency department of a tertiary care centre, Kavre, Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 61(1):39-42.

Smith-Oka, V. (2013) Shaping the motherhood of Indigenous Mexico. Vanderbilt University Press.

Storeng, K. T., & Béhague, D. P. (2016) Lives in the balance: The politics of integration in the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), 992-1000. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw023

Storeng, K. T., & Béhague, D. P. (2017) ‘Guilty until proven innocent’: The contested use of maternal mortality indicators in global health. Critical Public Health, 27(2), 163-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2016.1259459

Thaddeus, S., & Maine, D. (1994) Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine, 38(8), 1091-1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7

Varley, E., & Duplessis, E. (2023) The Global Safe Motherhood Initiative’s ‘unintended consequences.’ In C. Van Hollen & N. Appleton (Eds.), A companion to the anthropology of reproductive medicine and technology (pp. 119–137). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119845379.ch6

Wendland, C. (2016) Estimating death: A close reading of maternal mortality metrics in Malawi. In V. Adams (Ed.), Metrics: What counts in global health (pp. 57-81). Duke University Press.

Wong, K., & Brunson, J. (2025) Marshallese mothers navigating discrimination in Hawai‘i: Bwebwenato as method. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 39(3), e70008. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.70008

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 2 (2025), Issue 3 CC-BY-NC-ND