Housing as a social determinant of health: System perspectives from lived experience, policy and evidence

Research Article

Lisa M. Garnham1*, Katherine E. Smith 1, Ellen Stewart2, and Clementine Hill O’Connor2

1University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom 2University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, United Kingdom *Corresponding author: Lisa M. Garnham, lisa.garnham@strath.ac.ukPoor housing is a recognised contributor to poor health but, like many ‘wicked’ issues, policy intervention has proved challenging. This paper considers efforts to use systems mapping, a core systems science tool, to support housing policy teams in northern England to identify housing policy options to improve health. We compare housing-health systems maps created from three perspectives: (1) research evidence; (2) policymakers; and (3) people with lived experience. Employing Bevir & Rhodes’ 3Rs framework (ruling, rationalities and resistance), our analysis finds significant alignment between (1) and (2), reflecting an alignment between ‘ruling’ and ‘rational’ perspectives that is associated with efforts to achieve evidence-based policy. By contrast, lived experience accounts ‘resisted’ aspects of the policy and evidence-led maps, and offered markedly different insights. While all three maps reflected the four ‘pillars’ of housing (cost, condition, context and consistency), the maps created by people with lived experience underline the importance of people’s sense of ‘control’. We reflect on the need to decentre dominant ‘evidence cultures’ in policy and public health, concluding that, if systems science is to deliver on the promise of helping tackle ‘wicked’ policy issues, further innovation is needed, incorporating experiential evidence in ways that help address the unequal power dynamics at play.

Background

Housing is widely recognised as a key social determinant of health, with well-documented impacts on mental and physical health (Gibson et al. 2011, Sharpe et al. 2018, Swope & Hernández 2019). Beyond providing shelter (Thomson et al. 2013, WHO 2018), housing has social and psychological value (Karjalainen 1993, Preece & Bimpson 2019, Rolfe et al. 2020, Harris & McKee 2021), provides ontological security (Dupuis & Thorns 1998) and benefits mental health (Hiscock et al. 2001). Inequalities in access to good quality, affordable housing therefore contribute to health inequalities (Swope & Hernández 2019) and broader socio-economic and socio-demographic (dis)advantage (Angel & Bittschi 2019, Gurney 2023). Research and policy work on housing interventions often focus on mitigating homelessness and housing insecurity (Fowler et al. 2019, Nourazari et al. 2021). A public health prevention approach to housing policy would intervene earlier in the housing-health causal pathways (Newman et al. 2016) to prevent systemic health harms (Smith 1990, Swope & Hernández 2019).

Despite political support, implementing ‘whole system’ approaches remains challenging (Cairney et al. 2021, Amri et al. 2022, Such et al. 2022). The UK’s worsening housing crisis (Gibb et al. 2024) is complicated by the devolved and decentred governance system (Bevir 2022) and powerful market stakeholders, which combine to create a ‘chaotic picture of multiple actors’ (Bevir & Richards 2009). This makes identifying and implementing promising policy options challenging. In short, housing in the UK is a classic ‘wicked problem’, characterised by complex interactions, gaps in reliable knowledge, and enduring differences in values, interests and perspectives (Head 2022).

Traditional evidence-based approaches have not yielded anticipated policy progress (Head 2022), sparking a burgeoning interest in systems science for addressing ‘wicked issues’ (Haynes et al. 2020, Nguyen et al. 2023). Rather than focusing on discrete, manageable aspects, the interdisciplinary field of systems science emphasises within-system interconnections. While ‘harder’ systems science approaches, such as quantitative systems modelling, can explore contrasting policy scenarios, ‘softer’ qualitative approaches, such as rich pictures and participatory systems mapping, can facilitate shared understanding and identify areas to intervene.

While the UK government recognises this spectrum of systems science tools (Government Office for Science 2023), in practice, policy interest appears to have been piqued by the ‘harder’ end of the spectrum (Malbon & Parkhurst 2023). This aligns with HM Treasury’s emphasis on quantitative data analysis in the ‘Magenta’, ‘Aqua’ and ‘Green’ books, which guide central government approaches to analysis, appraisal and evaluation (HM Treasury 2020, 2022, 2023). However, this focus can obscure the partial and performative nature of models, creating ‘blind spots’ that go unchallenged (Marchionni 2022). These gaps are especially problematic for ‘wicked issues’ like housing, where data deficits, conflicting interests, and a complex accountability landscape complicate policymaking.

For these issues, ‘softer’ system tools, such as systems mapping, may foster holistic understandings of policy problems that facilitate more joined-up decision making (Barbrook-Johnson & Penn 2021, Meier et al. 2019, Hohn et al. 2023). The process of bringing stakeholders together to collectively develop systems maps can help overcome silo-based thinking (Ross et al. 2015), while maps themselves can be used to communicate diverse stakeholder perspectives (Bakhtawar et al. 2022). For housing and health, participatory mapping has the potential to facilitate shared understandings between, for example, policymakers focusing on health and policymakers focusing on housing. Moreover, qualitative analysis of maps could be used to identify ‘win-win’ interventions or clarify trade-offs between competing interests.

Decentring Perspectives on Housing and Health

This paper is informed by Bevir and Waring’s (2018) call for ‘decentred’ approaches to health systems analysis and Bevir and Rhodes’ (2016) call for work to critically assess the dominant narratives shaping policy. We employ Bevir and Rhodes’ (2016) three ‘Rs’ of ‘rethinking governance’, Ruling, Rationalities and Resistance, to critically reflect on our experiences using systems mapping with stakeholders in the UK housing-health policy system. This work was undertaken as part of a systems science research consortium that centred quantitative modelling, which involved collaborating with three policy organisations across the UK: the Scottish Government, Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and Sheffield City Council (SCC). All partners expressed an interest in computational modelling of the housing-health system.

As part of an exploratory process to plan modelling, we mapped the housing-health system from three perspectives: (1) the existing evidence base on housing as a social determinant of health; (2) policy perspectives (in GMCA) on housing-health links; and (3) the research consortium’s three Community Panels (based in Scotland, Manchester and Sheffield), who had lived experience of the stresses and challenges caused by inequalities.

In this paper, we undertake the task of ‘decentring’ (Bevir & Waring 2018) by unpacking and comparing the meanings and beliefs embedded within each of these perspectives. We posit that the similarities between the evidence-based and policy-led maps, and the more distinctive contribution of the maps created by people with lived experience, reflects a broader alignment between ‘ruling’ (policy) perspectives and that ‘rationalities’ captured in the types of evidence that dominate public health research. Specifically, we examine the rationalities embedded in both the evidence base and our policy partners perspectives, describe the resistance we encountered to these rationalities from the Systems Science In Public Health and Health Economics Research (SIPHER) Community Panel members, and outline the steps we undertook to reintroduce politicised concepts back into the evidence base presented to our policy partners on the housing-health system. In doing so, our analysis draws attention to unequal power dynamics between those with lived experience and those undertaking the process of ruling via evidence-based policymaking.

We examine whether systems mapping can support a decentred approach to evidence generation for decision-making, given policymakers’ reliance on quantitative data but their growing interest in lived experience insights (Hill O’Connor et al. 2023). We highlight the value of ‘soft’ systems approaches in bridging policy siloes, such as housing and health, and capturing the diverse and unequal stakeholder perspectives. The paper argues that, if policymakers are to leverage maximum value from systems approaches, more attention needs to be paid to developing and deploying tools that effectively capture and communicate lived experience perspectives and unequal power dynamics in integrative, meaningful ways.

Methods

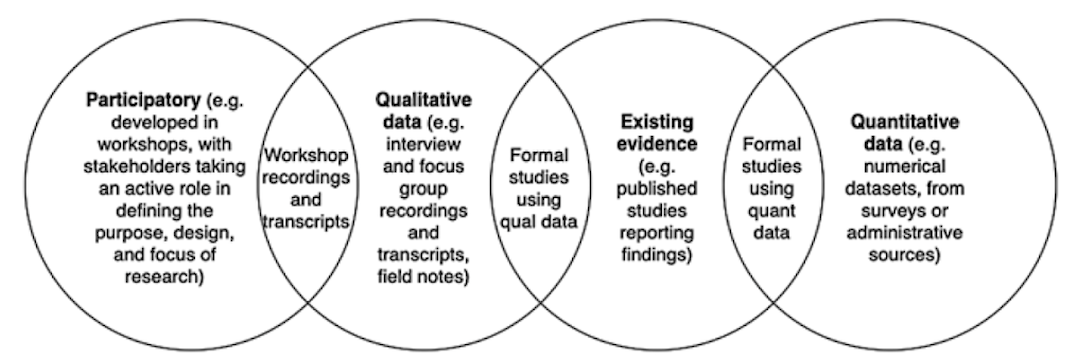

Systems mapping involves the building of ‘conceptual, visual representations of the components of the problem being considered’ (Barbrook-Johnson & Penn 2022), in this case the relationship between housing and health. Practically, this involves discussing and outlining a network of key factors within the system (the ‘nodes’) and the connecting relationships (typically shown with arrows). The resulting maps are mental models of real-world problems, and they reflect the perspectives of those who participate in mapping or those whose data are used to build a systems map. Maps are, therefore, one method through which perspectives on, and possibilities within, this system can be explored (Lane & Reynolds 2017, Barbrook-Johnson & Penn 2021). They can be created by drawing on a wide variety of sources, summarised in Figure 1.

In late 2022, we mapped the housing-health system using three sources: (1) existing evidence of housing as a social determinant of health; (2) policy actors, via participatory systems mapping; and (3) lived experience accounts of people from communities particularly affected by health inequalities, also via participatory systems mapping. The evidence base provided an overview of established housing-health pathways for policy partners. Participatory mapping with policy partners helped us understand policy perspectives and foster discussion across teams focusing on housing and health policy, while participatory mapping with SIPHER’s Community Panel members formed part of their role in scrutinising the broader research (see Stewart et al. 2024). This section describes the methods used to create these three maps, informed by Barbrook-Johnson & Penn (2022).

Figure 1: Sources from which systems maps can be created, from Barbrook-Johnson & Penn 2022, p.130, Fig.9.1 Types of information for building system maps and their overlaps. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

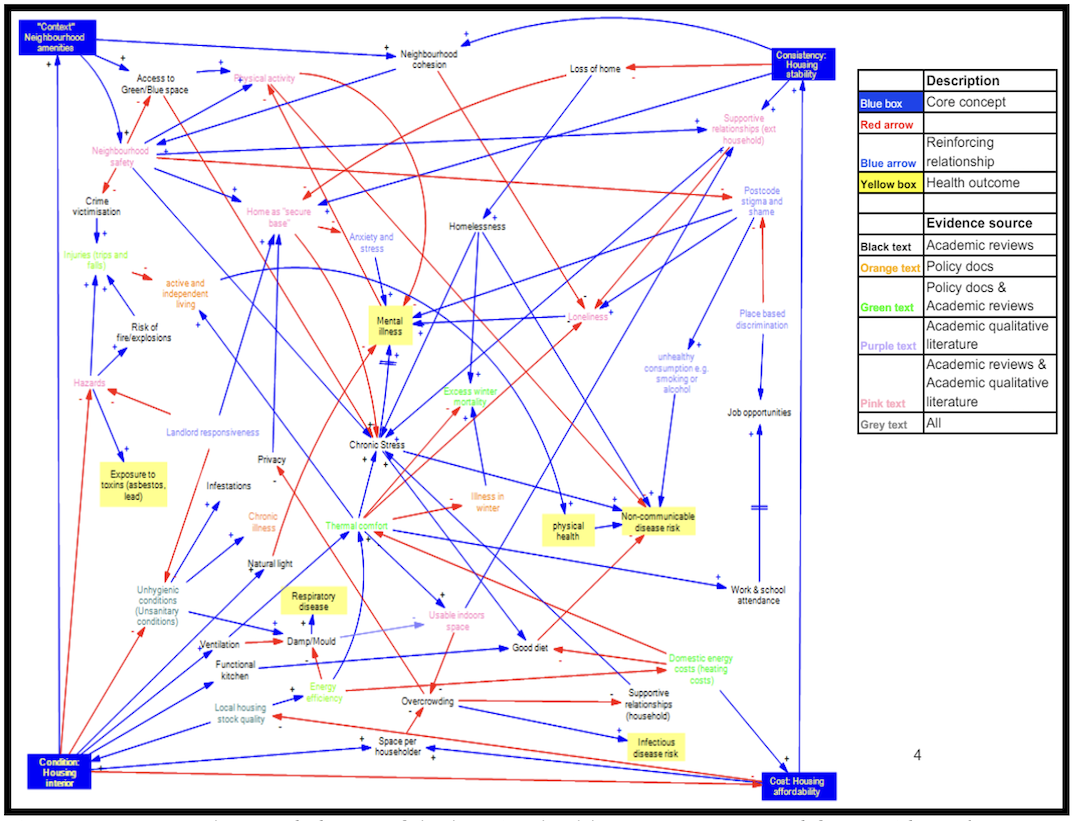

Map 1: Evidence Base

Map 1 was built using academic evidence and policy documents describing causal relationships between housing and health (see Appendix I for full list of the literature sources) and involved a three-step process. In step 1, we used evidence syntheses describing associations or causal links between housing and health (e.g. systematic reviews and conceptual models) to construct an initial, draft systems map. We used Swope & Hernandez’ (2019) four ‘pillars’ of housing to orientate this map (see dark blue highlights in Figure 2. Map 1):

- Cost (housing affordability)

- Condition (housing quality)

- Context (neighbourhood quality)

- Consistency (housing stability)

In step 2, we searched for primary qualitative research reporting people’s experiences of housing and health connections. Step 3 involved reviewing key housing documents produced by our three policy partners. In both of these steps, any new factors or pathways identified were added to the initial map (see Figure 2: Map 1, which uses colour-coding to differentiate underpinning evidence sources).

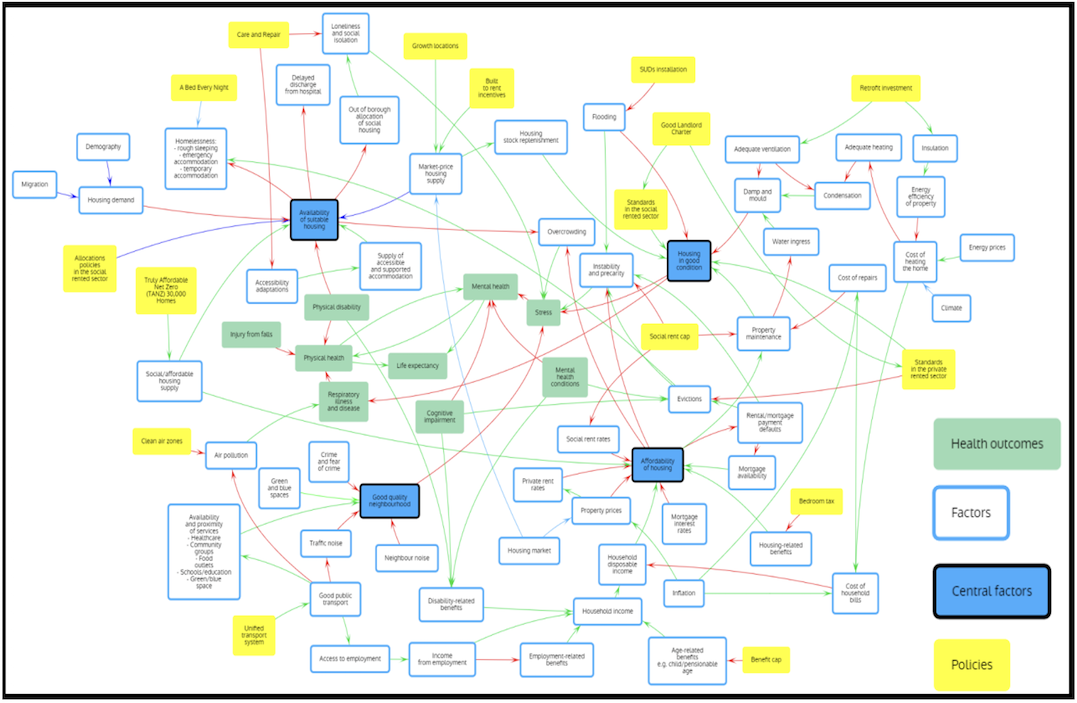

Map 2: Policy Partners

Map 2 captured policy perspectives on the housing-health system and was created via a half-day participatory workshop with 12 GMCA and NHS staff working on housing and health. After a brief introduction to systems mapping, participants split into three groups, each collaboratively mapping the housing-health system using post-it notes for factors and pen-drawn arrows to show connecting flows of influence. They were also asked to identify which policy goals and levers they felt might produce system change. Discussions were digitally audio-recorded and photographs of the maps were taken for analysis. Following the workshop, the three groups’ maps were amalgamated to produce one, integrated housing and health system map (Figure 3: Map 2). Detailed notes were compiled from the audio-recordings.

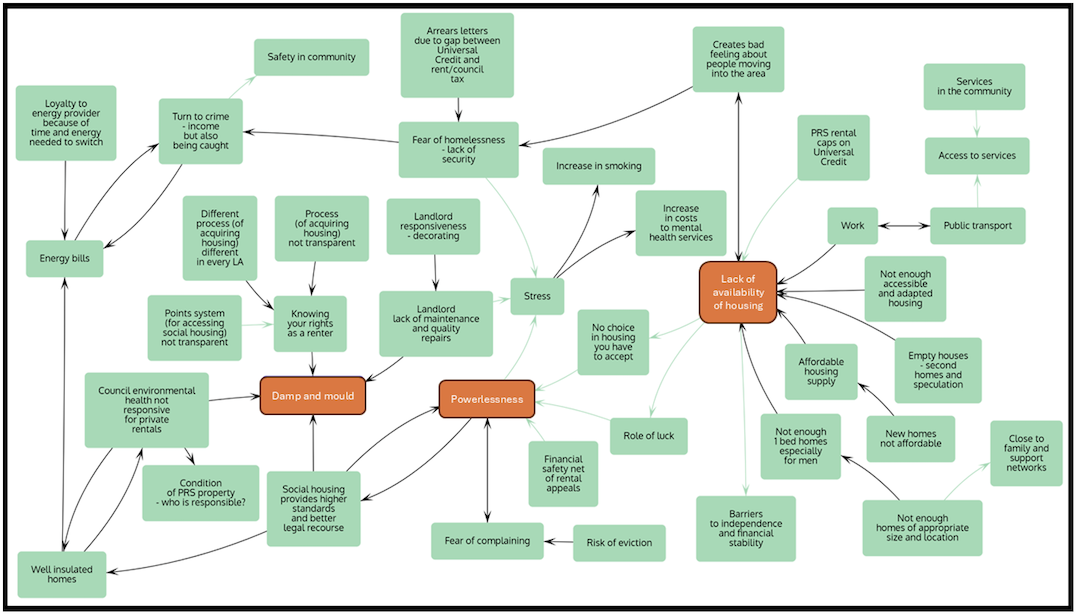

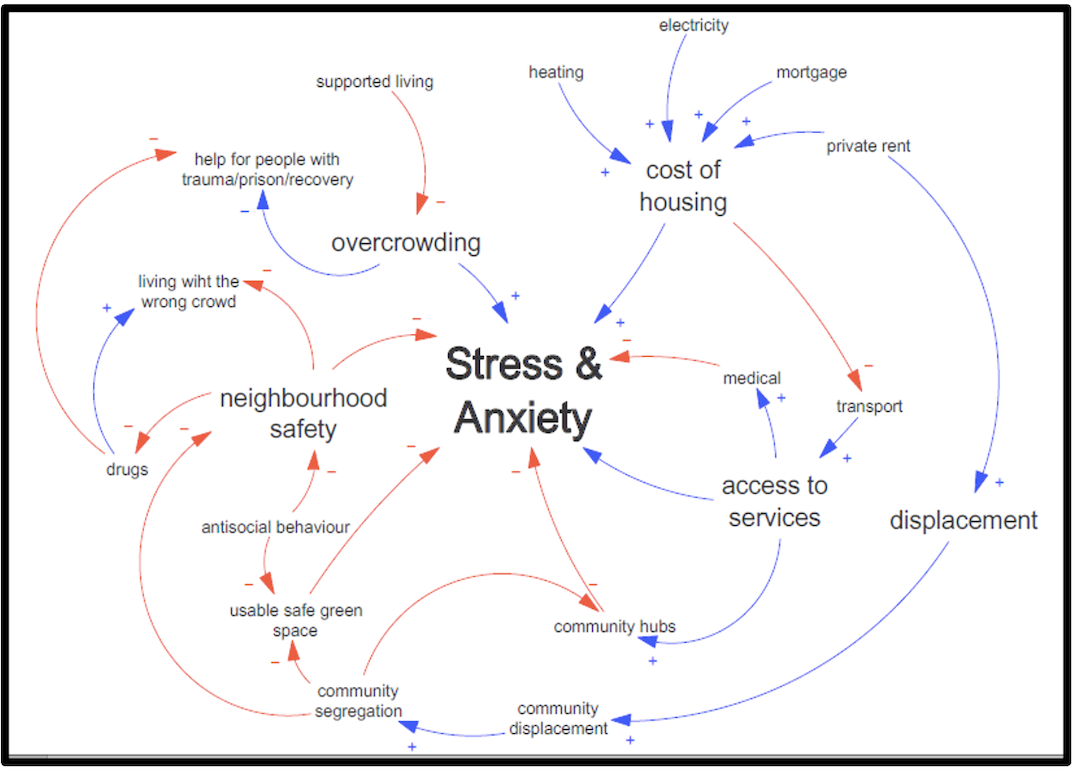

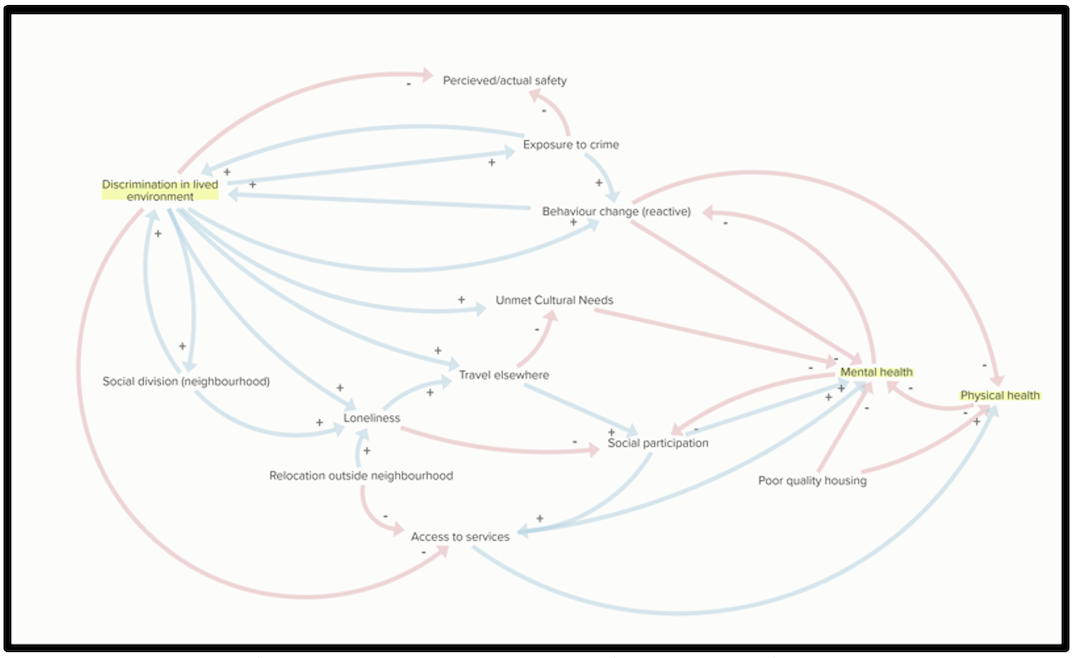

Maps 3-5: People With Lived Experience

We conducted participatory systems mapping with Community Panels in Scotland, Manchester and Sheffield (separately) through in-person, half-day workshops (Stewart et al. 2024 explains how and why the Community Panels were recruited). We began the sessions with a blank page and asked Panel Members, in groups, to map how their housing experiences were connected to their health, working together using post-it notes, pens and flip-chart paper as described above. Similar factors were grouped and arranged into systems maps to highlight interconnections by participants to create maps, which were later digitised by SIPHER researchers (see Figures 4-6: Maps 3-5). The research team then shared a large-scale printed version of the evidence-based map (Map 1) and asked Panel Members to compare it with their own. The ensuing discussion of similarities and differences was captured through researcher notes and photographs of the post-its and flipcharts.

Figure 2: Map 1 - colour-coded map of the housing-health system constructed from evidence base.

Figure 3: Map 2 - GMCA housing and health systems map, created through participatory systems mapping.

Figure 4: Map 3 - Scotland Community Panel causal loop diagram, created through participatory systems mapping.

Figure 5: Map 4 - Greater Manchester Community Panel causal loop diagram, created through participatory systems mapping.

Figure 6: Map 5 - Sheffield Community Panel causal loop diagram created through participatory systems mapping.

Comparison and Analysis

We compiled and compared factors identified in each map, analysing differences in frequency, framing of factor categories (cost; condition; context; consistency; physical health; mental health; other), and any differences in vocabulary used to describe similar concepts. We also examined upstream and downstream pathways for key factors (e.g. housing affordability, damp & mould, chronic stress, etc.) to assess differences in the frequency, density, location and direction of mapped connections across each map. We discussed and refined our comparative analysis by drawing on the contextual information contained within the notes taken during participatory mapping (for Maps 2-5) and broader publication content (for Map 1).

LMG (who was not involved in creating any of the initial maps) conducted the initial comparative analysis, which was reviewed by KES, ES and CHO, who were each involved in creating or facilitating the creation of Maps 1-5. Our interpretation was enriched by scoping research undertaken prior to the mapping, as well as ES’s four-year work with the Community Panels. This research received ethical approval from the University of Sheffield, Department of Health and Health Related Research for data collection with policy makers, while ethical approval for collecting data from SIPHER’s Community Panels (such as notes of workshops) was awarded by the University of Edinburgh School of Social and Political Sciences Research Ethics Group.

Findings

This section analyses the three perspectives on the housing-health system gathered during this systems mapping work. First, we highlight the strong alignment between Map 1 (evidence-base) and Map 2 (policy perspectives), proposing that this reflects the dominance of quantified rationalities in the knowledge (re)produced by public health researchers, with this knowledge both informing and reflecting the focus of policy work. We then explore the differences between these two maps and Community Panels’ perspectives (captured in Maps 3-5), exposing the limitations of prioritising dominant forms of knowledge. In the Discussion, we explore the potential for systems science research to challenge dominant narratives and facilitate resistance through research, via the use of participatory systems mapping to communicate non-dominant, lived experience perspectives.

Comparing Policy Perspectives with the Public Health Evidence Base

The policy partner generated map (Map 2) closely aligned with the map representing the evidence base (Map 1), particularly in the shared focus on measurable factors. For example, policymakers’ perspectives on housing condition centred primarily on the physical suitability of housing for different households’ needs (e.g. number of occupants and disability/adaptation needs), alongside incidence of damp and mould. This reflects the statutory duties placed on local government, the data gathered in the discharge of this duty, as well as the media and policy focus on damp and ventilation, following the tragic death of Awaab Ishak from respiratory failure in 2020, caused by chronic exposure to mould (eClinicalMedicine 2022).

In practice, this informs a focus on particularly poor-quality properties, at the expense of wider, systemic problems, which is underpinned by a lack of resources and regulatory frameworks to enforce housing quality improvements. This narrow focus is reinforced by the evidence base, which presents strong quantitative and causal evidence for the impacts of cold, damp and mould on physical health outcomes, while wider aspects of housing quality and condition are reported as demonstrating ‘weak’ links to health (e.g. Swope & Hernandez 2019). This makes it challenging for policymakers to locate evidence that interventions further upstream (i.e. before housing quality reaches extreme lows) will impact on health.

This focus on what is measurable was also evident in relation to neighbourhood context, where policy participants focused on the built environment, including blue and green spaces, pollutants and access to services. The social neighbourhood was largely characterised as consisting of crime and noise pollution, although householders’ desire to live near social and cultural networks was noted. While physical aspects of the neighbourhood environment were considered ‘within reach’ of policy, policy partners struggled to identify their role in intervening in less tangible, social aspects of the housing-health system, beyond meeting demands for additional support by those housed at a distance from their social networks. This focus on the measurable aspects of the neighbourhood was mirrored in many of the evidence sources (e.g. systematic reviews) used to create Map 1, reflecting the hierarchy of evidence embedded in public health research (Lorenc et al. 2014).

In looking further upstream, policy participants did incorporate wider contextual characteristics of the housing system, which was a departure from Map 1 (evidence-base). This included housing market forces, existing housing policy and a range of legislative and statutory responsibilities placed on local governments in the UK. Through discussion, many of the policy levers needed to address issues within the system were identified as sitting wholly or partially with the UK Government or other bodies and, therefore, out of the reach of those participating in the mapping exercise. That is, policy partners acknowledged a ‘chaotic picture of multiple actors’ (Bevir & Richards 2009), only some of whom they felt could be influenced or controlled through regional government policies.

The influence of these multiple and diverse stakeholders was evident in relation to all four ‘C’s (cost; condition; context; consistency) captured on the policy partner map but was strongest in relation to housing cost and consistency. Policy participants reflected that policy efforts to reduce housing costs and enhance stability had to be balanced against market interests, since private providers are relied on to fill ‘gaps’ in state-led housing provision. The extent to which it was possible, or even desirable, to control these aspects of the system was therefore a topic of some debate. These upstream influences on housing inequalities and outcomes (which, in turn, generate health outcomes) were not captured in our review of the housing-health literature, which is markedly depoliticised by comparison. This raises questions about the role of public health evidence for housing policymaking, given the power of these wider system stakeholders and the lack of prioritisation they seem likely to attach to health outcomes. Evidence examining the needs and perspectives of these wider system stakeholders, and the power dynamics at play, is required to help policymakers consider and navigate options for intervening in housing to improve health, in a system marked by competing interests.

Comparing Lived Experience with Evidence and Policy Perspectives

While the four key ‘pillars’ of housing (cost, condition, context and consistency) featured across Panel members’ discussions, the pathways to health in Maps 3-5 were more intricately connected than those in the evidence and policy-led maps (Maps 1 and 2). While mapping and discussing, Panel members often communicated their experiences through story-telling, invoking multiple pillars of housing simultaneously, describing causes or factors that acted in mutually reinforcing ways. They described multiple mini-feedback loops and reciprocal relationships that illustrate the experience of getting ‘stuck’ in certain parts of the housing system and feeling there are few (or no) pathways to improvements (e.g. ‘not knowing your rights as a tenant’ and ‘powerlessness’). Indeed, Panel members’ maps and discussion suggest it may be useful to think of a fifth ‘C’ in exploring the impacts of housing on health: Control. This section describes key themes in the experiences and perspectives on housing and health shared by Community Panel members.

Housing Costs, Paying for Housing and Securing Housing Quality

Housing affordability was considered by Panel members to be a central engine of the housing system and they highlighted a complex interaction between housing costs and housing-related social security subsidies in the UK. Social security is a key policy lever in this space, and both the evidence base and policy partner perspectives mapped the impacts of social security on health via reductions housing costs. However, for Panel members, it was the dynamic interaction between social security, housing costs and the gap between these two that had the most significant impact on chronic stress and mental health.

This focus on the way housing is paid for, and what Panel members needed to do to achieve this, rather than simply housing costs, was mirrored in discussions about housing quality. Panel members expanded the housing condition pillar to specifically include ‘repairs’ and their challenging experiences of securing repairs and maintenance for their homes to a sufficient standard. The crucial aspect here was not only the quality of the work undertaken but the process required by the householder to get repairs and maintenance issues addressed. From Panel members’ perspectives, relationships with landlords, fear of reprisals for making repair requests, and the stress of feeling powerless, all featured. This highlights the vital role of trust, relationships and power in shaping the impacts of housing quality on health, and the dynamism of this aspect of the housing-health system.

In contrast, both the evidence-base and policy accounts appeared to approach housing quality as a static building characteristic and provided little sense of the power structures that ultimately shaped people’s sense of self-worth and wellbeing. Developing an understanding of these pathways and the underlying power dynamics will be crucial in shaping effective housing policy over the coming decade. Some progress is being made on strengthening tenants’ rights across some parts of the housing system (e.g. the Social Housing Regulation Act 2023 in England and the Housing (Scotland) Bill in Scotland) but, while these changes help address a lack of legal rights for tenants, the impact of these and other prospective interventions are, as yet, unknown (Marsh et al. 2023). Our analysis suggests attention needs to be paid to assessing how these emerging policy changes influence tenant-landlord relationships, and to evaluating impacts on housing and health outcomes from tenant perspectives, as well as more measurable impacts, such as repairs undertaken, complaints received, eviction notices, and housing supply.

Stress, Emotions, Wellbeing and Mental Health

The perspective from both policy partners and the evidence base was that, while pathways to physical health impacts were relatively short, simple and discrete, a wide range of housing system factors contributed to chronic stress. This was echoed by Panel members, who concentrated predominantly on mental health outcomes when creating their maps, making only select references to physical health. Indeed, the mapping process appeared to be especially useful in drawing out the numerous, micro-level ways in which housing experiences cumulatively impact on mental wellbeing across the lifecourse.

This is evident in the centrality of ‘powerlessness’ to Panel members’ reflections on the housing-health system, and their accounts of never being able to ‘relax’. The broader system drivers of these experiences included a lack of housing supply, poor affordability of housing and the opacity of the processes through which (both social and private) housing are accessed and attained. These coalesced in experiences of ‘fear’ and ‘anxiety’, and of accounts describing how challenging it is to exercise rights, control or choice within the current UK housing system. These pathways were articulated in detail, emphasising the emotional toll of repeated negative experiences, which formed reinforcing feedback loops. Perhaps the most notable example of this was the seemingly pervasive threat of homelessness, which underpinned much of the fear and anxiety embedded within other housing experiences (e.g. reluctance to ask private sector landlords to make essential repairs, or to decline an unsuitable social housing offer).

Panel members also identified strong and multiple connections from mental health to housing experiences and outcomes, highlighting a feedback loop that was not strongly articulated in either the evidence-based or policy partner map. From these two perspectives, pathways are largely framed as the need for accessible and supported accommodation for people experiencing (physical and mental) ill health. However, Panel members described more complex and diverse pathways between poor mental wellbeing and housing. This included the propensity for negative housing experiences to hinder recovery from mental illness, addiction and trauma, and ways in which negative experiences made it harder to engage productively in the complex (and often marginalising) housing system.

Social Cohesion, Networks, Supports and Relationships

The evidence-based and policy-led maps both recognised that neighbourhood safety, social cohesion and place-based stigma feature within the housing-health system. However, Panel members highlighted that the objective safety of a neighbourhood was secondary to how a neighbourhood ‘felt’ to residents (i.e. perception was key). There was a significant extent to which this varied with gender, culture and ethnicity, meaning that some people feel safe or part of a socially cohesive neighbourhood in one place and not in another, while others experience the opposite. The generalising and ‘flattening’ processes involved in map-making was criticised by Community Panel members in this regard, coming to the fore in accounts of racism and discrimination, which were felt very acutely by some residents and not at all (or very differently) by other residents within the same neighbourhood. A further example was the presence of drugs or street drinking within a neighbourhood; a nuisance or safety issue for some residents, but a significant, tangible threat for re-traumatisation or interference with addiction recovery for others. The causal pathways from neighbourhood safety to health outcomes for these different groups were, therefore, substantially different.

Panel members also described causal pathways from pressures within the housing system to racism, discrimination and social fragmentation. Specifically, they cited a lack of availability of housing, poor neighbourhood infrastructure and high housing costs as generating ‘bad feeling about people moving into the area’ and social dislocation, which in turn feed into a lack of social cohesion and poor mental wellbeing. This is contrary to the framing of social cohesion in the evidence-based map, in which it is cast as a quantified feature of neighbourhoods, rather than as a feature of individuals’ experiences of neighbourhoods, and with no feedback loops between housing and health outcomes and neighbourhoods themselves.

Quality, not Quantity

Availability of housing was considered by Panel members to be another core engine within the housing system, aligning with the evidence and policy maps. However, Panel members’ perception was that new housing was largely being built cheaply, without sustainability or energy efficiency goals in mind. Panel members focused not so much a lack of housing (although this was an acute problem in some locations) but on a lack of good quality, efficient, affordable and appropriate housing, driving other problems within the system.

Similarly, views on green and blue space within neighbourhoods varied significantly among Panel members. The local, natural context was described as key to establishing the types of spaces needed by residents, as well as the quality of these spaces, how they were used and by whom. For one Panel, green spaces had become a source of social conflict and a space where social divisions within the neighbourhood played out. In this sense, they were not an asset so much as a source (and illustration) of neighbourhood denigration. For another Panel, green spaces were present and appreciated but considered to be of poor quality and poorly maintained. Once again, it was not the objectively measured number, size or quality of green and blue spaces (featuring in the policy and evidence led maps) that was the issue for Panel members but the ways in which these spaces were being used that featured in pathways to health.

Choice and Control

A recurring theme of Panel members’ accounts was that they lacked choice in, and therefore control over, their housing experiences, across a range of housing factors or outcomes, and that this had a significant, pervasive impacts on their health. Control could therefore be considered as a fifth core ‘pillar’, to be added to the four identified by Swope & Hernandez (2019) in capturing how housing impacts on health. Restrictions on choice and a sense of control appeared to underlie Panel members’ persistent references to powerlessness and fear, as well as their sense that ‘luck’ is a key factor in positive outcomes. This was especially the case where individuals or households had specific needs that constrained their housing options, such as disability, a large family, or a desire to be close to existing social support networks, or to avoid problematic social contacts.

This inhibited the ability of households to balance their own needs and make the compromises between the other four ‘pillars’ of housing (cost; condition; context; consistency) to suit their specific needs, characteristics and aspirations; that is, it significantly limited their ability to enact resistance from within the housing system itself. Moreover, the ruling rationalities of both the evidence base and policy makers perspectives on housing and health define the terms of the policy debate in ways that limit the capacity of marginalised populations to articulate and communicate their experiences and gain any meaningful control through influencing the policy process.

Discussion

This analysis has demonstrated strong alignment of perspectives from the public health evidence base (Map 1) and that of policy-makers (Map 2). We propose that this reflects dominant ‘evidence cultures’ within UK policymaking and public health (Lorenc et al. 2014, Hill O’Connor et al. 2023, Bandola-Gill 2024), which place a high value on quantified data and systematic evidence reviews and highly metricised rationalities. Reflecting this, policy participants in the mapping workshop regularly referred to quantitative research evidence (albeit not necessarily the specific papers used to build Map 1) to support claims they were making while map-building.

From the perspective of Bevir & Rhodes’ (2016) 3Rs framework, this represents the success of efforts to achieve evidence-based policy, demonstrating an alignment between ‘ruling’ policy perspectives and the rationality embedded within public health evidence. It is unsurprising, then, that the maps produced from the evidence-base and through participatory systems mapping with policy partners fundamentally overlapped, including their incorporation of all four ‘C’s; Cost, Condition, Context and Consistency (Swope & Hernandez 2019). However, policy partners also highlighted the extent to which significant aspects of the system fell beyond their reach. This reflects the fact that, even where the (quantified) evidence-base supports intervention, significant negotiation with multiple actors (who may not be primarily concerned with the health of local populations) is required to achieve system change (Bevir & Richards 2009).

Despite this, the power dynamics at play in the housing-health system were not explicit in the established housing-health evidence base. By contrast, those same power dynamics were at the centre of lived experience perspectives and in the identification of a destructive cycle in which acts of system resistance were severely inhibited through a lack of control over housing choice. The community panel generated maps also underline the importance of acknowledging that particular social groups, and households, have very different experiences of similar housing and neighbourhoods (e.g. due to experiences of racism, or to particular social needs), emphasising the limitations of public health actors’ concern with population level trends. A lack of recognition of the fundamental role of power in the rationalities through which evidence-based policymaking takes place undermines the extent to which policymaking might successfully intervene in the pathways from housing to health.

Reflections on Systems Mapping as a Research Tool for ‘Wicked Issues’

As health inequalities researchers, we were aware of the overriding quantitative rationality in research and policymaking at the outset of this research. This is why, in step 2 of building Map 1, we sought to incorporate causal pathways identified in qualitative research. Despite this, Community Panel members still felt the resulting evidence-based map was ‘flat’ and lacking meaning. However, when Panel members participated directly in the research and mapped the system from their own perspectives, they were able to bring less tangible aspects of housing experiences to the fore, with a focus on the roles of emotion and social relationships.

Moreover, their emphasis on the centrality of the processes required to secure certain housing outcomes highlighted the need for attention to the ways outcomes are achieved. This suggests that a core value of this method is the direct participation of people with lived experience in the mapping process, rather than simply the inclusion of lived experience perspectives gathered through qualitative research. It is this engagement and participation in mapping that has the potential to force a decentring of dominant rationalities (re-enacted, apparently, even by reflexive qualitative researchers).

However, the participatory mapping process is not unproblematic. For one, the collaborative nature of participatory mapping centred aspects of the housing-health system that were most easily defined and agreed by participants, while less common experiences may be sidelined (despite potentially offering important insights). Second, the visual nature of the maps encouraged a focus on aspects participants felt able to depict with boxes and arrows, with discussions suggesting that significant aspects of the experiences and perspectives shared by Panel members were not easily translated into this format, echoing similar findings by Ross et al. (2015).

Policy partners did not struggle with this aspect of participatory mapping to the same extent, perhaps because they mapped much more from a professional perspective taking a ‘bird’s eye’ view of the system, rather than trying to navigate the system from within. The ways in which participatory systems mapping can or should be used as a tool for capturing different system perspectives, then, is clearly influenced by the orientation that different participants have towards that system.

Systems Mapping as a Tool for Decentring Dominant Perspectives in Evidence-Based Policymaking

This comparison included an assessment of both the content of the systems maps generated from three perspectives, as well as more foundational issues about the nature and form of the knowledge contributed and elucidated via three distinct processes of developing systems maps. In our broader efforts to engage in systems science research, a recurrent challenge has been integrating lived experience perspectives in meaningful and equitable ways that reinforce, rather than undermine resistance to, dominant narratives, whilst also generating useful evidence for policy audiences. Participatory systems mapping with Community Panels brought significant insights into the housing-health system that were not reflected in either the evidence-based or the policy-led maps. It has been suggested that part of the value of systems science approaches is that it is possible to integrate diverse types of evidence (O’Donnell et al. 2017). However, integration is challenging when one source (in this case, lived experience perspectives) provides alternative accounts that are not always compatible with dominant rationalities, and which also involve elements of active critique and resistance.

An alternative approach would have been for us to use participatory systems mapping to bring those with lived experience of the housing-health system together with policymakers, to facilitate sharing perspectives. However, as others note (e.g. Barbrook-Johnson & Penn 2022), different perspectives on a system bring different levels of granularity, as well as attaching different levels of priority to particular aspects. There are also ethical and practical challenges in bringing stakeholders with different degrees of power together in one space. Ultimately, we chose to map the housing-health system with policy partners and Community Panel members separately due to concerns about power imbalances and the potential for uncomfortable emotions (such as anger, despair and frustration) to create difficult engagement experiences. The findings reinforced our sense that this was the right decision.

However, mapping with stakeholders separately then generated challenges in communicating the insights offered by Community Panel members to policy partners. This was complicated by the fact that the process of creating maps tended to transform individuals’ experiences and thoughts in distinctive ways and the format of the map, as a standalone visual, was not a sufficient communication tool. Indeed, much of the deep insights we gained from participatory systems mapping with the Community Panels came from the stories they told us, and one another, while they mapped. While rich dialogue is often cited as one of the strengths of participatory mapping processes, we were left with the challenge of finding a means to enmesh rich narratives with visual maps, in a way that respected and foregrounded the value of lived experience, a challenge also identified by Barbrook-Johnson & Penn (2021).

Our sense is that, where diverse perspectives do not align, or prove challenging to integrate, decisions about how to orientate and present findings need to be cognisant of existing power imbalances and researchers must reflect on the role they play in reinforcing existing rationalities or underpinning resistance to those (and for whom) as they carry out that integration. Elsewhere (Garnham et al. 2024), we describe how we attempted to respond to this challenge by developing a layered systems map embedding evidence and lived experience narratives. This is just one attempt to heed Bevir & Rhodes’ (2016, p.18) call to ‘enhance the capacity of citizens to consider and voice differing perspectives’ in debates about housing and health. Our view is that further critical reflection and work is needed if systems science policy tools are to enable the inclusion of diverse perspectives.

Conclusion

Traditional approaches to tackling wicked issues, such as housing crises and health inequalities, have struggled to achieve the desired success (Head 2022), stimulating interest in systems science (Haynes et al. 2020, Nguyen et al. 2023). Rather than breaking the problem into parts, these approaches consider complexity by examining system wide relationships. This paper reflects on using qualitative, participatory systems mapping, a core systems science tool, to explore different perspectives on the UK’s housing-health system.

Using evidence and policy perspectives to create systems maps reinforces dominant rationalities, rooted in a ‘culture of evidence’ within UK policy and public health that prioritises readily available, metricised data that do not adequately capture people’s lived experiences (Hill O’Connor et al. 2023). In the case of housing and health, the maps created from the evidence base and through participatory mapping with policymakers both tended to focus attention on established, objectively measurable factors in mapping out pathways for policy intervention.

By engaging with systems science critically, and through working to decentre dominant perspectives (Bevir & Waring 2018), we show how systems mapping can identify additional insights from marginalised perspectives. Capturing the perspectives of people with lived experiences of housing and health challenges provides insights that identify neglected factors and connecting pathways, while foregrounding the importance of affective influences (Ferrer & Ellis 2019).

This perspective on housing and health suggests that ‘Control’ represents a fifth ‘pillar’ to Swope & Hernandez’ (2019) original four capturing the impacts of housing on health: Cost; Condition; Context; and Consistency. It also draws attention to power dynamics within the housing-health system that negatively impact on more marginalised populations. If the burgeoning interest in systems science continues, it is incumbent on those developing and applying these approaches and tools to ensure that they are not deployed uncritically. In public health, systems science researchers have already made a strong case for incorporating policy and practice perspectives (O’Donnell et al. 2017). We hope this paper underlines the value of paying at least as much attention to the views and experiences of those who are ultimately the target of policy changes.

Author Contribution Statement

Lisa M Garnham: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; writing - original draft. Katherine E Smith: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; funding acquisition; investigation; writing – review & editing. Ellen Stewart: conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; funding acquisition; investigation; writing – review & editing. Clementine Hill O’Connor: formal analysis; methodology; investigation; visualization.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Community Panels and policy partners who took the time to engage in systems mapping with us. The research was conducted as part of the Systems Science In Public Health and Health Economics Research (SIPHER) Consortium and particular thanks go to Corinna Elsenbrioch and Jenny Llewellyn, who each supported one Panel Member session in participatory systems mapping and Petra Meier, who contributed to the creation of the evidence-based map. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Social Policy Association conference in Glasgow in July 2024.

Funding

This work was supported by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (MR/S037578/2), which is funded by the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research, Natural Environment Research Council, Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), The Health Foundation and Wellcome.

Orcid IDs

Lisa M. Garnham https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9242-8095

Katherine E. Smith https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1060-4102

Ellen Stewart https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3013-1477

Clementine Hill O’Connor https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1693-1697

References

Amri, M., Chatur, A., & O'Campo, P. (2022) Intersectoral and multisectoral approaches to health policy: an umbrella review protocol. Health Research Policy and Systems 20(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-022-00826-1

Angel, S., & Bittschi, B. (2019) Housing and health. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(4), 495-513.

Bakhtawar, A., Bachani, D., Grattan, K., Goldman, B., Mishra, N., & Pomeroy-Stevens, A. (2022) designing for a healthier Indore, India: Participatory Systems Mapping. Journal of Urban Health, 99(4), 749-759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-022-00653-3

Bandola-Gill, J., Andersen, N. A., Leng, R., Pattyn, V., & Smith, K. E. (2024) A matter of culture? Conceptualizing and investigating "Evidence Cultures" within research on evidence-informed policymaking. Policy and Society, 43(4), 397-413. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puae036

Barbrook-Johnson, P., & Penn, A. (2021) Participatory systems mapping for complex energy policy evaluation. Evaluation, 27(1), 57-79.

Barbrook-Johnson, P., & Penn, A.S. (2022) Systems mapping: How to build and use causal models of systems. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bevir, M. (2022) What is the decentered state? Public Policy and Administration, 37(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076720904993

Bevir, M., & Rhodes, R.A.W. (2016) The ‘3Rs’ in rethinking governance. In M. Bevir & R.A.W. Rhodes (Eds.), Rethinking governance. Routledge.

Bevir, M., & Richards, D. (2009) Decentring policy networks: A theoretical agenda. Public Administration, 87(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2008.01736.x

Bevir, M., & Waring, J. (2018) Decentring health policy: traditions, narratives, dilemmas. In M. Bevir & J. Waring (Eds.), Decentring health policy: Learning from British experiences in healthcare governance. Routledge.

Cairney, P., St Denny, E., & Mitchell, H. (2021) The future of public health policymaking after COVID-19: A qualitative systematic review of lessons from Health in All Policies. Open Research Europe 1(23). https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13178.2

Dupuis, A., & Thorns, D.C. (1998) Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security. The Sociological Review, 46(1), 24-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00088

eClinicalMedicine (2022) Awaab Ishak and the politics of mould in the UK. eClinicalMedicine, 54, 101801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101801

Ferrer R.A., & Ellis, E.M. (2019) Moving beyond categorization to understand affective influences on real world health decisions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 13(11), e12502. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12502

Fowler, P. J., Hovmand, P.S., Marcal, K.E., & Das, S. (2019) Solving homelessness from a complex systems perspective: Insights for prevention responses. Annual Review Public Health, 40, 465-486. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013553

Garnham, L., Stewart, E., & Smith, K.E. (2024) SIPHER Layered Systems Map: Experiences and evidence of housing and health methodological appendix. SIPHER. https://eprints.gla.ac.uk/342104/1/342104.pdf

Gibb, K., March, A., & Earley, A. (2024) Homes for all: A vision for England’s housing system. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence. https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/web_Homes-for-All_A-Vision-for-Englands-Housing-System.pdf

Gibson, M., Petticrew, M., Bambra, C., Sowden, A. J., Wright, K. E., & Whitehead, M. (2011) Housing and health inequalities: A synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place, 17(1), 175-184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.011

Government Office for Science. (2023) Introduction to systems science for civil servants. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/systems-thinking-for-civil-servants/introduction

Gurney, C. M. (2023) Dangerous liaisons? Applying the social harm perspective to the social inequality, housing and health trifecta during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Housing Policy 23(2), 232-259. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1971033

Harris, J., & McKee, K. (2021) Health and wellbeing in the private rented sector: Part 1 literature review and policy analysis. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE). https://housingevidence.ac.uk/publications/health-and-wellbeing-in-the-private-rented-sector-part-1-literature-review/

Haynes, A., Garvey, K., Davidson, S., & Milat, A. (2020) What can policy-makers get out of systems thinking? Policy partners' experiences of a systems-focused research collaboration in preventive health. International Journal of Health Policy Management, 9(2), 65-76. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.86

Head, B. (2022) Wicked problems in public policy: Understanding and responding to complex challenges. Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature.

Hill O’Connor, C., Smith, K., & Stewart, E. (2023) Integrating evidence and public engagement in policy work: an empirical examination of three UK policy organisations. Policy & Politics, 51(2), 271-294. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321x16698031794569

Hiscock, R., Kearns, A., MacIntyre, S., & Ellaway, A. (2001) Ontological security and psycho-social benefits from the home: Qualitative evidence on issues of tenure. Housing, Theory and Society, 18(1-2), 50-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090120617

H.M. Treasury (2020) The Magenta Book: Central government guidance on evaluation. OGL Press. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-magenta-book

H.M. Treasury (2022) The Green Book: Central government guidance on appraisal and evaluation. OGL Press. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-government/the-green-book-2020

H.M. Treasury (2023) The Aqua Book: Guidance on producing quality analysis. OGL Press. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-aqua-book-guidance-on-producing-quality-analysis-for-government

Höhn, A., Stokes, J., Pollack, R., Boyd, J., Chueca Del Cerro, C., Elsenbrioch, C., … & Katikireddi, S. V. (2023) Systems science methods in public health: What can they contribute to our understanding of and response to the cost-of-living crisis? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 77, 610-616. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2023-220435

Karjalainen, P. T. (1993) House, home and the place of dwelling. Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research, 10(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02815739308730324

Lane, A. & Reynolds, M. (2017) Systems thinking in practice: Mapping complexity. In S. Oreszczyn & A. Lane (Eds.) Mapping environmental sustainability: Reflecting on practices for participatory research. Bristol University Press.

Lorenc, T., Tyner, E. F., Petticrew, M., Duffy, S., Martineau, F. P., Phillips, G., & Lock, K. (2014) Cultures of evidence across policy sectors: Systematic review of qualitative evidence. European Journal of Public Health, 24(6), 1041-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku038

Malbon, E., & Parkhurst, J. (2023) System dynamics modelling and the use of evidence to inform policymaking. Policy Studies, 44(4), 454-472. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2022.2080814

Marchionni, C. (2022) Social aspects of economics modelling: Disciplinary norms and performativity. In B. Caldwell, J. Davis, U. Maki, & E. Sent (Eds.) Methodology and history of economics. Routledge.

Marsh, A., Gibb, K., Harrington, N., & Smith, B. (2023) The impact of regulatory reform on the private rented sector. Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE). https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/20231020_ImpactofRegulatoryReforminPRS_V3.pdf

Meier, P., Purshouse, R., Bain, M., Bambra, C., Bentall, R., Birkin, M., … &. Watkins, C. (2019) The SIPHER Consortium: Introducing the new UK hub for systems science in public health and health economic research. Wellcome Open Research, 4, 174. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15534.1

Newman, L., Ludford, I., Williams, C., & Herriot, M. (2016) Applying Health in All Policies to obesity in South Australia. Health Promotion International, 31(1), 44-58. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau064

Nguyen, L.-K.-N., Kumar, C., Jiang, B., & Zimmermann, N. (2023) Implementation of systems thinking in public policy: A systematic review. Systems, 11(2), 64. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-8954/11/2/64

Nourazari, S., Lovato, K., & Weng, S.S. (2021) Making the case for proactive strategies to alleviate homelessness: A systems approach. International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health, 18(2), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020526

O’Donnell, E., Atkinson, J. A., Freebairn, L., & Rychetnik, L. (2017) Participatory simulation modelling to inform public health policy and practice: Rethinking the evidence hierarchies. Journal of Public Health Policy, 38, 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-016-0061-9

Preece, J. & Bimpson, E. (2019) Housing insecurity and mental health in Wales: an evidence review. UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE). https://housingevidence.ac.uk/publications/housing-insecurity-and-mental-health-an-evidence-review/

Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., Anderson, I., Seaman, P., & Donaldson, C. (2020) Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09224-0

Ross, H., Shaw, S., Rissik, D., Cliffe, N., Chapman, S., Hounsell, V., … & Schoeman, J. (2015) A participatory systems approach to understanding climate adaptation needs. Climatic Change, 129(1), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1318-6

Sharpe, R. A., Taylor, T., Fleming, L. E., Morrissey, K., Morris, G., & Wigglesworth, R. (2018) Making the case for "Whole System" approaches: Integrating public health and housing. International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health, 15(11), 2345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112345

Smith, S. J. (1990) Health status and the housing system. Social Science & Medicine 31(7): 753-762.

Stewart, E., SIPHER Greater Manchester Community Panel, SIPHER Scotland Community Panel, & Such, E. (2024) Evaluating participant experiences of Community Panels to scrutinise policy modelling for health inequalities: The SIPHER Consortium. Research Involvement and Engagement 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-023-00521-7

Such, E., Smith, K. E., Woods, H. B., & Meier P. (2022) Governance of intersectoral collaborations for population health and to reduce health inequalities in high-income countries: A complexity-informed systematic review. International Journal of Health Policy Management 11(12), 2780-2792.

Swope, C.B., & Hernández, D. (2019) Housing as a determinant of health equity: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 243, 112571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112571

Thomson, H., Thomas, S., Sellstrom, E., & Petticrew, M. (2013) Housing improvements for health and associated socio‐economic outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(2), Art. No.: CD008657. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008657.pub2

WHO (2018) Housing and health guidelines. World Health Organization. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535293/

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 3 (2026), Issue 1 CC-BY-NC-ND