Measuring social inequalities in self-reported miscarriage experiences in the United Kingdom

Research Article

Heini Väisänen1* and Katherine Keenan2

1Institut National d’Etudes Démographiques (INED), Aubervilliers, France 2School of Geography and Sustainable Development, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, UK *Corresponding author: Heini Väisänen, heini.vaisanen@ined.frAn estimated one in four pregnancies end in a miscarriage. Miscarriage may affect fertility intentions and worsen mental and physical health. Yet, we know little about how social inequalities affect the risk of experiencing miscarriage, and the few existing studies show mixed results. A social gradient in the risk of miscarriage may be related to societal structures shaping risk factors, such as stress, health behaviours, and age at pregnancy. We use the British Cohort Study (1970) to investigate whether individuals’ socioeconomic characteristics are associated with their likelihood of self-reporting a miscarriage over the reproductive life course. We apply a multi-level discrete-time event-history model to examine this likelihood according to occupational social class, income, and education. Our results are affected by the sub-population studied: among all women, those socioeconomically more disadvantaged have a higher risk of miscarriage at younger ages, but the direction of the association reverses towards the end of the reproductive life span. These differences disappear when analysing only those who self-reported a pregnancy. Methodological work tackling misreporting of miscarriage and other pregnancy outcomes is needed for more reliable estimates. A better understanding of this common reproductive event can help policy makers improve reproductive and population health.

Introduction

Between 12 and 25% of recognised pregnancies are lost[1] (Delabaere et al. 2014, Larsen et al. 2013, Quenby et al. 2021). Despite how common miscarriages are, and their known negative impact on health and wellbeing (Farren et al. 2020, Geller et al. 2004, Morris et al. 2015, San Lazaro Campillo et al. 2019), relatively little is known about their risk factors, particularly when it comes to social (dis)advantage. Genetic abnormalities, which have been estimated to account for around 45% of first miscarriages and 39% for subsequent ones (van den Berg et al. 2012), and parental health factors (such as metabolic/endocrinological causes including thyroid disorders and autoimmune diseases; uterine or genetic abnormalities) cause miscarriages (Christiansen et al. 2008, Larsen et al. 2013). However, there are likely to be social and structural processes which affect the likelihood of miscarriage via these factors as well as via other causes, such as health behaviours. For instance, genetic abnormalities of the embryo/foetus increase by parental age (ESHRE Early Pregnancy Guideline Development Group 2017) and the age at pregnancy is linked to social status. Parental health is also affected by socioeconomic factors.

One reason for the limited amount of research on miscarriage is the lack of high-quality data. Miscarriages are likely to be underreported in surveys making it difficult to study the social gradient of miscarriage as underreporting is likely to vary by social status (Lindberg & Scott 2018). We discuss some of these difficulties in measuring miscarriage and the potential consequences of these shortcomings on research for this topic. Thus, we discuss potential social inequalities in experiencing a miscarriage, while highlighting the need for further methodological work. We also demonstrate the need to carefully choose the right denominator, as the results are greatly affected by these choices.

This study uses data from the British Cohort Study 1970 (BCS70), which collected data for 17,000 people born in the United Kingdom in 1970 over repeated sweeps (University College London, UCL Social Research Institute, Centre for Longitudinal Studies 2024). Thus, we have data on almost the entire reproductive span of the sample. Participants are asked to report their full pregnancy history (timing and outcome of each pregnancy) and comprehensive aspects of their socio-demographic characteristics, health, and partnerships, enabling us to take a life course perspective and examine miscarriage through the intersection of age and socioeconomic position. This has not been studied previously, despite age being an important risk factor for miscarriage.

Social Inequalities in the Risk of Miscarriage

Social disadvantage is associated with many adverse reproductive health outcomes, such as gestational diabetes, preterm birth, and neonatal death (Christian 2012, Gissler et al. 2009, Hardie & Landale 2013, Hein et al. 2014, Jardine et al. 2021, Joseph et al. 2007), but less is known about miscarriage. To date, studies that explore the link between social inequality and the likelihood of miscarriage provide mixed results across and within country contexts. Many studies are conducted using non-representative or outdated data; do not correct for any potential underreporting of miscarriage and often do not take a life course perspective, despite the likelihood of both pregnancy and miscarriage depending strongly on the intersections of age and socioeconomic status.

Education has been inconsistently linked with miscarriage in Europe and the USA. In Italy from the 1970s to 1990s, no link between women’s education and the risk of miscarriage was found (Osborn et al. 2000). However, in the early 1990s, low education was associated with a higher risk of miscarriage in Milan (Parazzini et al. 1997) and in the early 2000s, education had an inverted U-shape relationship with the risk of miscarriage in Italy (Caserta et al. 2015). In 1996-2002 in Denmark, low education increased the risk of miscarriage (Norsker et al. 2012), but in 2000-2009, high education did so (Hegelund et al. 2019). In the UK, a population-based study in 2001 found no association between education status and miscarriage (Maconochie et al. 2007). Updated evidence is needed, given the results overall are inconsistent and all but two of these papers are more than 15 years old.

Depending on context, unemployment and income might be linked with miscarriage. A Danish study found a positive association between aggregate unemployment and miscarriage rates (Bruckner et al. 2016), but did not examine the association at the individual-level. A longitudinal study between 2009 and 2022 in the UK showed an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth if the pregnant person or their partner lost their employment during pregnancy (Di Nallo & Köksal 2023), but an earlier study in the UK found no association between unemployment and miscarriage (Maconochie et al. 2007). Studies in Denmark (Norsker et al. 2012) and the USA (Nguyen et al. 2019) found a link between low income and higher risk of miscarriage.

A better understanding of such a gradient, and how it varies over time and contexts, can provide a better understanding of this common reproductive event. Such understanding may give tools for policy makers to improve reproductive health by tackling modifiable risk factors and structural inequalities in health.

Mechanisms and Conceptual Framework

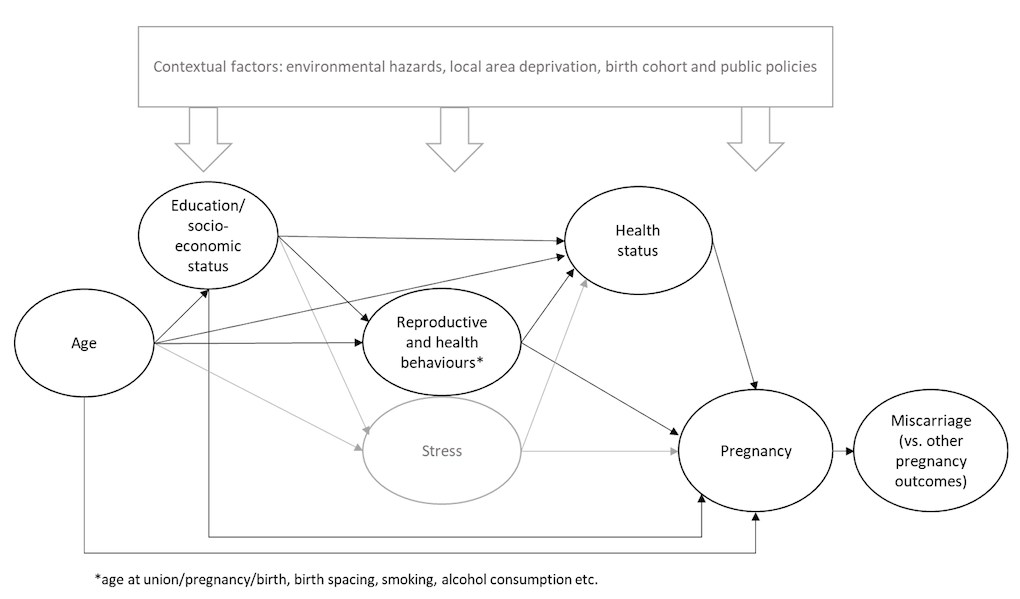

Miscarriage risk may have a social gradient because structural conditions in the society tend to increase experiences of stress, poor health (and related behaviours) and obesity among those from poorer backgrounds, with less education, with a low occupational status, and/or living in a deprived area (Cockerham et al. 1997, Link & Phelan 1995). These groups may be disproportionally more likely to experience a miscarriage, as poor health (and some health behaviours), obesity, and stress are known risk factors (Cohen et al. 2006, Jurkovic et al. 2013, Larsen et al. 2013, Magnus et al. 2019, Marmot et al. 2020, Quenby et al. 2021, Temple et al. 2002). Higher age at pregnancy, on the other hand, is a risk factor that is more common among those with higher education, income, and/or occupational status (de La Rochebrochard & Thonneau 2002, Quenby et al. 2021). The relevant risk factors and vulnerabilities associated with miscarriage risk are specific not only to the wider context in which the individuals operate, but also to their socioeconomic and reproductive life course pathways, as reproductive strategies might develop out of intersecting socio-demographic characteristics and how these interact with the dominant culture surrounding them (Geronimus 2003).

The mechanisms linking social disadvantage and miscarriage are likely to function via the four risk factors mentioned above: health and health behaviours, low/high Body Mass Index (BMI), stress, and age at pregnancy. First, there is a social gradient in health (Marmot et al. 2020), whether measured by individual characteristics like education and income or area-level structural socioeconomic deprivation. Various health issues, including metabolic (e.g. low or high BMI) or hormonal (e.g. hyperthyroidism) conditions and many bacterial and viral infections increase the risk of miscarriage (Antoniotti et al. 2018, Giakoumelou et al. 2016, Kakita-Kobayashi et al. 2020, Quenby et al. 2021). As those in socioeconomically deprived situations as a result of structural inequalities are more likely to suffer from these health issues, this may lead to a higher risk of miscarriage for them.

In terms of health behaviours during pregnancy, there is some evidence on the relationship between a higher miscarriage risk and: alcohol consumption (Andersen et al. 2012, Delabaere et al. 2014, García-Enguídanos et al. 2002, Larsen et al. 2013, Quenby et al. 2021); smoking (Delabaere et al. 2014, Feodor Nilsson et al. 2014, Garcıia-Enguídanos et al. 2002, Pineles et al. 2014, Quenby et al. 2021, Wisborg et al. 2003), and caffeine consumption (Andersen et al. 2012, Delabaere et al. 2014, Feodor Nilsson et al. 2014, García-Enguídanos et al. 2002, Greenwood et al. 2010, James, 2021, Larsen et al. 2013). Health behaviours are not independent of social status, which could consequently increase social inequalities in miscarriage risk.

Both high and low BMI have been linked with a higher miscarriage risk (Quenby et al. 2021). However, it is not clear whether BMI alone or other factors associated with it, such as physical activity, diet, or insulin resistance cause this association (McLean & Boots 2023). Nevertheless, in the UK obesity is more common among socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals, which could increase social inequalities in the likelihood of miscarriage.

There are no studies proving a direct causal link from stress to (recurrent) miscarriage, due to lack of prospective studies measuring stress both before and after miscarriage (ESHRE Early Pregnancy Guideline Development Group 2017), but many studies have found an association (Qu et al. 2017, Quenby et al. 2021). Stress may be linked to miscarriage via immune parameters: stress affects the immune response, which can lead to inflammation resulting in preterm contractions (Christian 2012). Stress attenuates inflammatory responses, which can increase the risk of miscarriage. Such responses can be higher for those with social disadvantage, but they are not well understood among pregnant people (Christian 2012). Higher cortisol levels may also increase the risk of miscarriage (Nepomnaschy et al. 2006). Precarity in the labour and/or housing market, for instance, increases stress (Julià et al. 2020) through processes like social marginalisation (Macmillan & Shanahan 2022), again those with fewer economic resources may face a higher miscarriage risk.

Finally, older age at pregnancy (often considered as 35 years or older for the pregnant person and 40 and above for their partner) is a key risk factor for miscarriage and linked to a risk of aneuploidy (that is, the embryo/foetus being genetically abnormal) (de La Rochebrochard & Thonneau 2002, García-Enguídanos et al. 2002). As childbearing postponement in Europe is concentrated among those with higher education (Kneale & Joshi 2008, Berrington et al. 2015), the risk of miscarriage among these groups might increase. However, in age-adjusted analyses, low education may be expected to increase the risk of miscarriage, due to the mechanisms discussed above. Taking into account the complex interplays of structural conditions, social status, age, health, and health behaviours, these aspects are of key importance for understanding miscarriage risk.

Although not the focus of this paper, there are also many contextual or area-level factors postulated to contribute to higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriage. These may include area-level deprivation, environmental exposures such as air pollution and pesticides (Ha et al. 2022, Quenby et al. 2021), and public policies. As many of these environmental harms cluster, and socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals are more likely to live in areas with these kinds of contextual exposures, these may exacerbate social gradients observed.

The conceptual framework of this project is based on the mechanisms discussed above (Figure 1), summarising socio-behavioural paths to miscarriage.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework.

Notes: aspects not measured in this study indicated in grey.

Aims and Research Questions

We aim to understand whether there are social inequalities in the risk of experiencing a miscarriage over the life course, and to explicate the key methodological challenges in estimating the relationships between social inequalities and miscarriage risk. We study the experiences reported by the same women followed up over time from age 16 until age 42. Our research questions are:

- Are education, income, and occupational status associated with the risk of reporting a miscarriage?

- Do these associations vary by age or depend or the denominator used?

We also discuss whether underreporting of miscarriage is likely to affect our empirical results.

Methods

Data Sources and Variables

We use sweeps 4 to 9 of the British Cohort Study (BCS70), which collects data on individuals born in 1970. These sweeps took place at ages 16, 26, 30, 34, 38 and 42, thus capturing most of the reproductive life span of participants. If a respondent missed a sweep(s), they were included again at their return.

Our outcome variable is self-reported miscarriage collected within a pregnancy history module, which records the month, year and outcome of each pregnancy between the most recent report (or start of reproductive life span when first asked) and the interview. The same individual may experience more than one miscarriage throughout the follow-up period of the study. We measure whether they reported at least one miscarriage between two sweeps to simplify our statistical analyses. The BCS70 collected retrospective information about full pregnancy histories at sweeps 6, 7 and 8. At sweep 9, full histories of pregnancies not leading to live births were collected, but live births were excluded. However, we inferred this information from the survey’s person grid by analysing the ages of the members of the household and their relationship to the respondent. At sweep 7, due to a routing error in the survey tool, while information about the number of miscarriages was collected, we have no information about the year they took place. Thus, if the respondent had missed sweep 6, we did not know whether the reported miscarriages took place between sweeps 6 and 7 or earlier. We thus imputed the years by randomly generating integers within a plausible range, which was taken from other pregnancies reported in the survey for which information on timing was available. There were 330 miscarriages in sweep 7 for which the year was missing. However, 298 of these happened to respondents who took part in sweep 6 and therefore we assumed that the miscarriage took place between sweeps 6 and 7. The value was thus imputed for 24 pregnancies where the respondent did not take part in sweep 6 but timing information was available also on earlier and/or later pregnancies, which narrowed the possible range. Eight miscarriages did not fall into any of these categories and were dropped.

We use individual-level variables to measure social inequalities, although future studies should also consider including partner’s and parent’s characteristics or local area deprivation for a more comprehensive view of the relevant socioeconomic aspects. We measure education based on age at leaving education (up to 16, 17-18, or post 18 years of age). Occupational status has three categories (non- or partly skilled workers; skilled workers; and managerial positions or higher). Income is measured in relation to all other respondents of the survey in three categories: bottom 20%, middle 60% and highest 20%.

In our multivariable analyses we control for the following variables, updated at the beginning of each sweep: parity (number of live births), whether reported having a cohabiting/marital partner, whether reported currently smoking, and whether suffered from at least one long-term health issue. These variables were chosen as they have been linked with the likelihood of experiencing a pregnancy and/or miscarriage in previous research. Our analytical strategy (as explained below) also takes into account the respondent’s age, which is divided into five categories based on their age when interviews were conducted: 16-25, 26-29, 30-33, 34-37, and 38-41 years.

In order to divide the studied population into relevant sub-groups, we include information about other pregnancies (self-reported retrospectively at sweeps 6-9 as explained above): live births, induced abortions, and stillbirths. First, we analyse all respondents identifying as women and having participated at least once between sweeps 4 and 9 (from now on ‘full sample’). We examine this group to estimate inequalities in miscarriage risk among women overall and to overcome any issues of underreporting of non-live birth pregnancy outcomes, which affects the second group we examine: respondents who reported a pregnancy in an age group, identify as women, and took part at least once between sweeps 4 and 9 (from now on, termed the ‘pregnancy sample’). This analysis better captures the population at risk of experiencing the event, as one cannot experience a miscarriage without first being pregnant, but we likely miss some respondents from the analyses due to underreporting.

Previous studies examining socio-demographic risk factors for miscarriages have used similar designs to our ‘full sample’ (Caserta et al. 2015) and ‘pregnancy sample’ (Hegelund et al. 2019, Norsker et al. 2012, Osborn et al. 2000). Other denominators have also been used, including live births only, to study miscarriage/birth ratios (Bruckner et al. 2016, Nguyen et al. 2019, Parazzini et al. 1997, de La Rochebrochard & Thonneau 2002), all pregnancies continuing beyond 13 gestational weeks (Maconochie et al. 2007), or all pregnancies except induced abortions (Di Nallo & Köksal 2023). We rejected these latter approaches, as we wanted to include all pregnancies observed in our dataset in the ‘pregnancy sample’ for the denominator to be as accurate as possible.

Analytical Strategy

We ran multi-level discrete-time event-history models including a woman-level random intercept to account for clustering among those who experience more than one miscarriage. The model is specified as follows:

<

Where MISC is the probability of miscarriage during interval t for individual i, αDti is the baseline logit hazard and Dti is a vector of function of time t (i.e. the five age categories described above). Vectors of explanatory variables pertaining to socioeconomic status (SES) and the control variables (CON) listed above of individual i at time t are added. An interaction is allowed between SES and age (. ui represents an error-term capturing unobserved time-invariant woman-specific factors associated with the risk of miscarriage (including biological woman-level risk factors). These effects are assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero.

After conducting descriptive analyses, we ran six multi-level discrete-time event-history models representing the three measures of socioeconomic position (occupational class, income and education) and the two analytic samples (full sample and pregnancy sample). We first included age and all the control variables mentioned above, but as ‘long-term illness’ was not significant in any of the models, it was dropped from the final models presented here.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

There were 8,943 women included in our analysis. They reported 1,908 miscarriages for which the year of pregnancy was known or imputed (see above), but as our outcome variable measures was whether at least one miscarriage was reported within each of the five age-groups included, we analysed 1,534 instances of such reports. Table 1 shows the number of respondents reporting at least one pregnancy or at least one miscarriage in each age group and the percentage of all pregnancy reports that were miscarriages.

|

Age |

Pregnancy, N |

Miscarriage, N |

% miscarried* |

|

16-25 |

2,339 |

390 |

16.7 |

|

26-29 |

2,470 |

368 |

14.9 |

|

30-33 |

2,081 |

276 |

13.3 |

|

34-38 |

1,490 |

286 |

19.2 |

|

39-41 |

605 |

214 |

35.4 |

Table 1: Number and percentage of respondents reporting at least one pregnancy or miscarriage by age.

Notes: * % miscarried calculated based on reporting at least one pregnancy/miscarriage within each age group rather than the ‘raw’ pregnancy/miscarriage numbers.

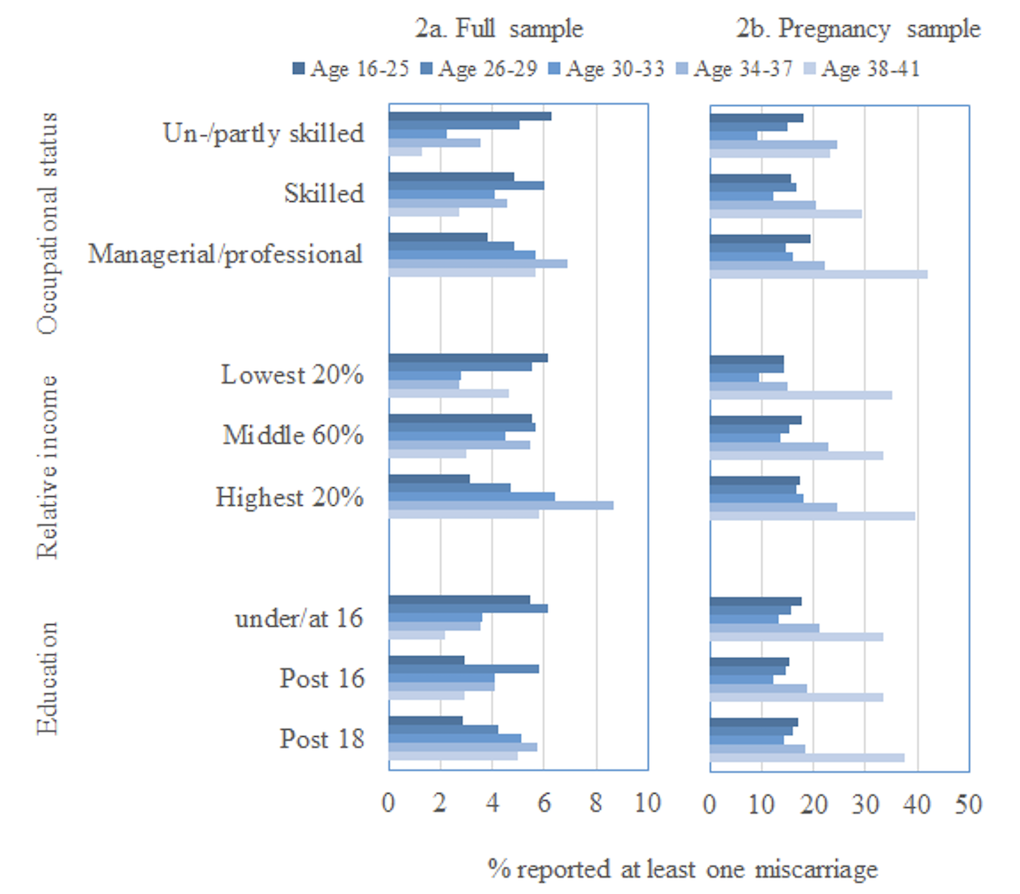

Figures 2a and 2b show the percentage of respondents reporting at least one miscarriage by age group and socioeconomic characteristics for full and pregnancy samples, respectively. Among younger age groups lower socioeconomic status is associated with a higher likelihood of reporting a miscarriage, but the direction of the association is the opposite for those in their 30s and 40s in the full sample, whereas in the pregnancy sample the risk varies less by socioeconomic group. Appendix I shows the exact number of women in each age- and socioeconomic group. The number of respondents in each group varies due to some respondents skipping sweeps and item non-response.

Multivariable Results

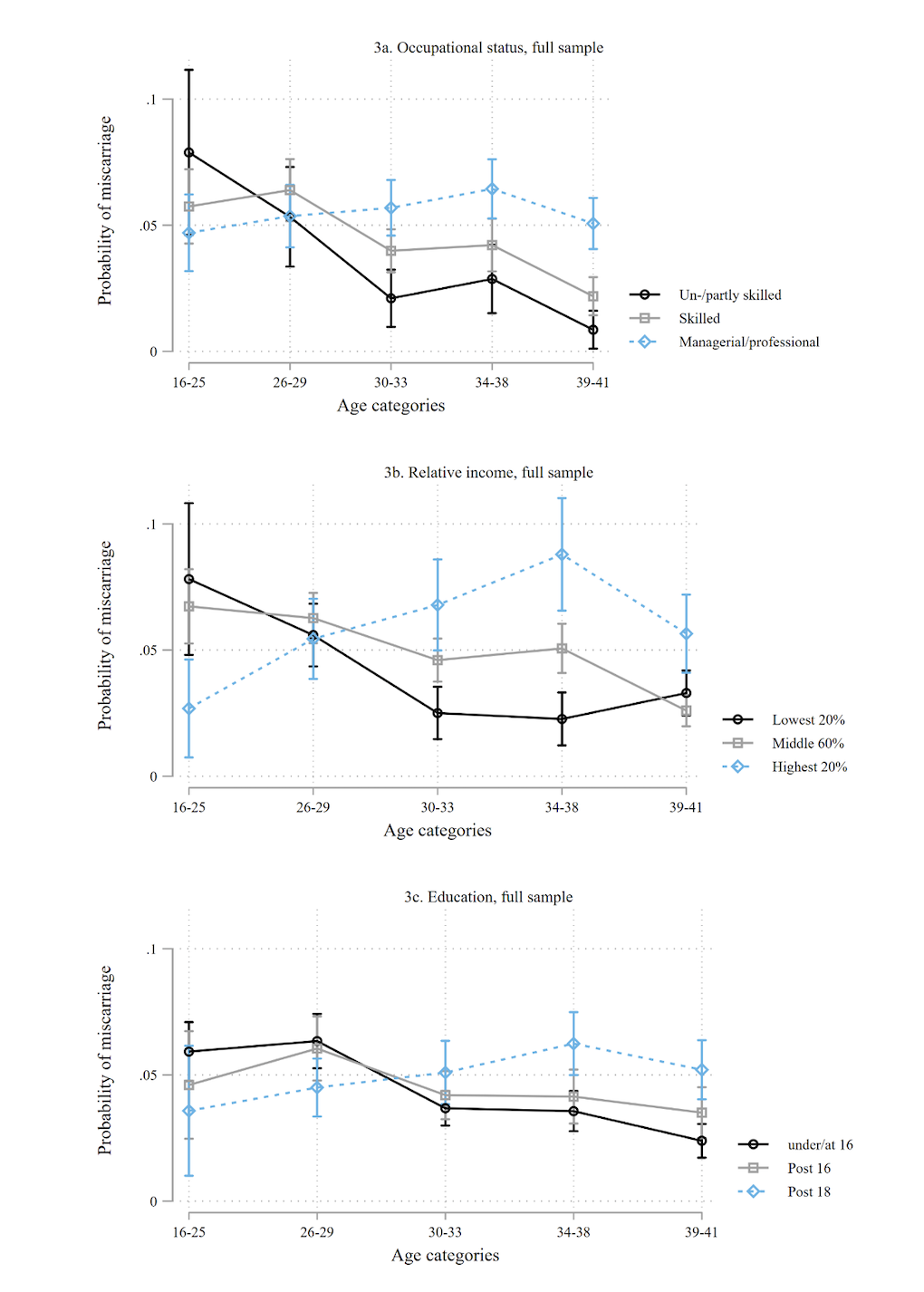

We present the results of our multi-level discrete-time event-history models as predicted probabilities of reporting at least one miscarriage by age group and each of the three markers of social status. We first analysed the ‘full sample’ (see Data Sources and Variables section). Figure 3 shows the predicted probabilities of reporting at least one miscarriage by age group and each measure of socioeconomic status. The models control for partnership status and smoking. The associations for the three variables of interest are very similar: while more disadvantaged women are more likely to experience a miscarriage in their teens and twenties, the direction of the association flips for those in their 30s or early 40s. However, this analysis includes all women respondents, some of whom were not at risk of experiencing a pregnancy (and subsequently a miscarriage), so in part we are capturing the likelihood of becoming pregnant rather than the likelihood of reporting a miscarriage.

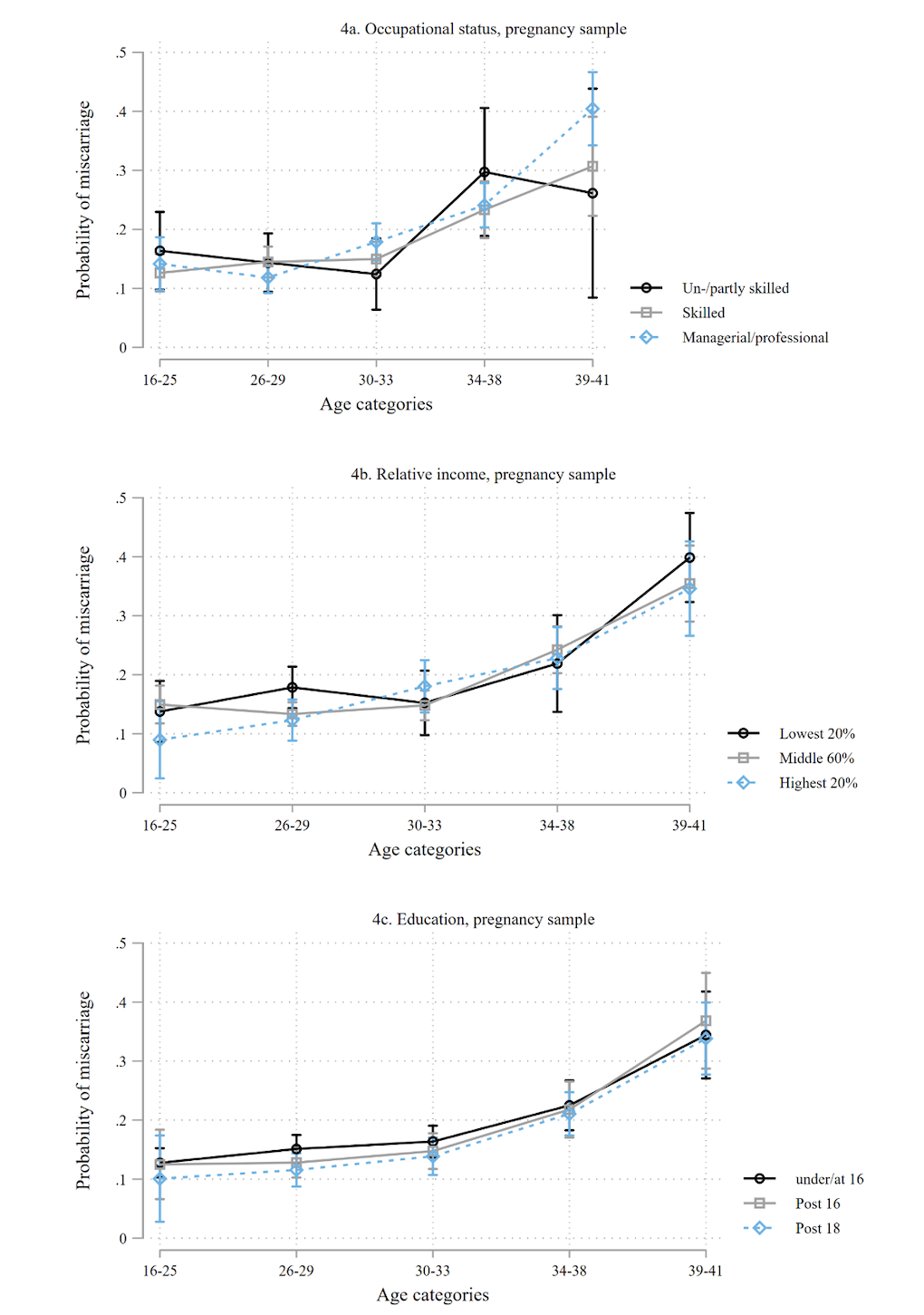

Next, we only included those respondents who reported at least one pregnancy within an age group. Figure 4 shows the predicted probabilities of reporting at least one miscarriage by age group and each measure of socioeconomic status among the pregnancy sample. The models control for partnership status and smoking. In this analysis the differences by occupational status, income, and education seen among the full sample disappear, suggesting that among pregnant respondents there are no socioeconomic differences in the likelihood of reporting a miscarriage. However, we might have missed some respondents in the denominator that were pregnant, as induced abortions and miscarriages tend to be underreported in surveys (Lindberg & Scott 2018).

Full results of the six models presented in Figures 3-4 are shown in Appendix II.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents reporting at least one miscarriage by age and socioeconomic position (occupational class, relative income and age left education).

Notes: the x-axes vary.

Figure 3: Predicted probabilities of reporting at least one miscarriage by age and (a) occupational status, (b) relative income, (c) age left education; full sample.

Notes: controlling for partnership and smoking.

Figure 4: Predicted probabilities of reporting at least one miscarriage by age and (a) occupational status, (b) relative income, (c) age left education; pregnancy sample.

Notes: controlling for partnership and smoking.

Discussion

Who Is ‘at Risk’ of Miscarriage?

We show that socioeconomic differences in self-reported miscarriage risk are found when all women respondents are analysed. Women with higher education, income and/or occupational status were less likely to self-report a miscarriage at younger ages, but more likely to do so in their 30s and 40s. However, the effect is probably due to the likelihood of experiencing a pregnancy, as these differences disappeared when only pregnant respondents were analysed. Thus, the choice of denominator is crucial. Neither strategy captures perfectly the group at risk of experiencing a miscarriage, as the first includes individuals who are not at risk of experiencing a pregnancy (and subsequently a miscarriage), for instance due to the specific nature of their sexual activities or lack of such activity, infecundity, or contraceptive choices. The pregnancy sample, while it might be more appropriate from an epidemiological perspective, is likely to undercount the denominator because it misses those who did not report their pregnancy: around half of induced abortions tend to be underreported (Lindberg et al. 2020) and miscarriages are likely to be underreported as well (Lindberg & Scott 2018), as discussed in more detail below.

Placing these results within a critical vulnerabilities framework to understand disparities in miscarriage, we should consider how social structures condition the timing and likelihood of pregnancy and childbearing. It is argued that reproductive strategies might develop out of intersecting socio-demographic characteristics and how these interact with surrounding dominant cultures (Geronimus 2003). That is, on average, the timing of pregnancies may have been suitable for each person under the structural and societal conditions in which they live, which would explain the lack of association between socioeconomic characteristics and miscarriage risk. Future studies should investigate this in more detail, as a lack of association is somewhat surprising given that many other reproductive outcomes have social gradients (Christian 2012, Gissler et al. 2009, Hardie & Landale 2013, Hein et al. 2014, Jardine et al. 2021, Joseph et al. 2007). The lack of association may also be due, in part, to the small number of pregnant high-SES women among the younger pregnant sample and a lack of low-SES women in the older pregnant sample.

Structural conditions intersecting with socio-demographic characteristics may affect miscarriage risk through the likelihood of experiencing a pregnancy, because more pregnancies lead to more miscarriages. In addition, among young people, a relatively high proportion of pregnancies typically end in an induced abortion (Ashcraft et al. 2013, Väisänen & Murphy 2014). Thus, we may have observed more miscarriages among those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds in the full sample, because some pregnancies that would have ended in miscarriage were aborted, and those who abort are more likely to be from advantaged backgrounds (Ashcraft et al. 2013, Väisänen & Murphy 2014).

On the other hand, the results among the pregnancy sample show that older age at pregnancy increases miscarriage risk, which is in line with other studies (de La Rochebrochard & Thonneau 2002, García-Enguídanos et al. 2002). This aligns with the biomedical construction of advanced age mothers as ‘high risk’. Yet, the relationship between age and miscarriage risk might be more complex, as associations between maternal age and pregnancy outcomes may depend on the societal context and cohort examined. For instance, in the UK, advanced age at childbearing used to be linked with lower birthweight and reduced cognitive ability of the child, but the relationship has since reversed (Goisis et al. 2017, Goisis et al. 2018). This provides an interesting opportunity to consider how vulnerability is constructed, develops from biomedical and social understandings in the context of miscarriage, and intersects (or not) with individual-level socio-demographic characteristics. Future research should investigate whether the interactions between age, socioeconomic status and miscarriage risk have changed by cohort.

Misreporting of Pregnancies and Implications

Miscarriages may be underreported in surveys due to miscarriage stigma, for example (Bardos et al. 2015, Bommaraju et al. 2016), but there are few studies on the topic. One study in the USA showed miscarriages were underreported in face-to-face interviews, but less than abortions (Lindberg & Scott 2018). The probability of reporting may depend on social status, as is the case for abortion: those with high income in the USA were more likely to report their abortions, but paradoxically those with higher education were less likely to do so (Lindberg et al. 2020). If the likelihood of reporting a miscarriage by social status is similar to that of induced abortion, our results might miss some miscarriages experienced by women with lower education or higher income. However, the US context is different from that of the UK and the underreporting mechanisms for abortion may differ from those for miscarriage. Thus, a careful analysis of levels of and social inequalities in reporting patterns of miscarriage is needed in future studies before definitive conclusions regarding the link between social status and pregnancy loss in the UK are drawn.

Recall problems may result in underreporting in retrospective studies. In this study this is likely to affect particularly the reporting of miscarriages experienced at a young age, as a full pregnancy history was collected for the first time at age 30. After that, data on miscarriage was collected every four years, which is likely to reduce recall problems. Miscarriages could also be underreported in a pregnancy history module by starting with asking the number of pregnancies ever experienced, as some respondents may not include miscarriages in the count. Cognitive interviews could shed further light on this issue.

Another matter complicating miscarriage reporting is that it can only be reported if the respondent knew that they were pregnant before the miscarriage took place. Circumstances surrounding the pregnancy and characteristics of the pregnant individual may be associated with the likelihood of detecting an early pregnancy. Those in a more advantageous socioeconomic position and those planning a pregnancy are more likely to detect an early pregnancy (Watson & Angelotta 2022). In addition, pregnancies are typically detected very early in the context of fertility treatments, which are more likely among those close to the end of their reproductive span and among more wealthy respondents, given both groups are more likely to postpone childbearing and be able to afford such treatments (Goisis et al. 2020). This could increase the number of miscarriages reported particularly among more socioeconomically advantaged individuals in their mid- to late 30s and early 40s in our study. On the other hand, the concept of pregnancy planning differs by socio-demographic groups and is particularly problematic among young people with limited economic prospects, thus making it less likely for these groups to detect an early miscarriage (Gomez et al. 2021).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

There were limitations in the study in addition to the potential underreporting of miscarriage discussed above. First, as this is a longitudinal study, some respondents drop out over time or skip sweeps (the number of respondents included in our analytic sample in sweeps 4 to 8 were n=5,799, n=4,900, n=5,790, n=5,038, and n=4,665, respectively). Attrition tends to be dependent on socioeconomic characteristics, which could affect the results of this study. In BSC70 respondents from higher socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to drop out (Mostafa & Wiggins 2014), which may mean that we missed some miscarriages at later ages among those with lower socioeconomic position if they dropped out from the panel. This would overestimate the miscarriage risk of those with higher socioeconomic position.

Second, as noted, due to a routing error in the survey instrument, timing of miscarriages was not recorded for most respondents at sweep 7. While we imputed these values using the strategy described above, some of the miscarriages may have been attributed to the wrong time window. However, we decided to use this strategy rather than, for instance, multiple imputation, because: it is not straightforward to specify the model in a way that would take into account the plausible timeframe of the event for each individual; it applied to only around 30 miscarriages; and we were able to infer the timing of miscarriage based on timing of births in some cases, as the pregnancy histories are collected in an order starting from the most recent pregnancy and the timing of pregnancy was collected for births. Future studies could explore other strategies such as Bayesian approaches for imputing this information.

Third, we were not able to study or control for all variables that might be relevant for miscarriage risk (see Figure 1), as they were not measured in the dataset used. These include, for instance, pregnancy specific health behaviours (smoking, alcohol consumption, and caffeine intake); environmental factors (e.g. pollution or pesticide levels); or stress levels of the pregnant person before and after miscarriage. However, we included proxies of such variables whenever possible, such as smoking at the time of each survey interview or reporting long-term health issue(s). Future studies with these variables should investigate whether these explain any socially diverse pathways to miscarriage.

The strengths of the study include opening new avenues for research by examining a neglected topic and highlighting the need for further methodological work on miscarriage. The dataset used, even if it may not cover all miscarriages, is exceptional in collecting comprehensive data on socio-demographic and health characteristics, and life events, repeatedly over time, allowing us to take a life course perspective. This study is one of the first steps in a larger research programme investigating social inequalities in the risk and consequences of miscarriage in Europe using individual and contextual-level measures of inequalities. Thus future work will expand a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon.

Conclusions and Implications for Policy

In order to better understand who is at risk of miscarriage, better data are needed. While surveys are an important source of such data, and undoubtedly more could be done around improving miscarriage reporting in them, governments could also tackle the issue of lack of data by routinely collecting data on miscarriage. Currently most countries (including the UK) that routinely collect information about miscarriage only include miscarriages that were treated in a hospital. Routine data collection in primary care would help us capture more of uncomplicated early miscarriages, which do not need an intervention in a hospital. If these data were linked to socio-demographic information and made available for researchers, it could be used alongside surveys to better understand the phenomenon.

Researchers should pay careful attention to denominators they use. It is important to acknowledge that as long as data on all pregnancy outcomes is not reliably recorded and reported, we are not able to correctly identify the population at the risk of experiencing a particular pregnancy outcome. In addition, more comprehensive longitudinal information on contraceptive use and sexual activity could help better identify the population at risk of conception. While such information might be collected in specialist surveys on sexuality and sexual behaviours, such as Natsal (University College London et al. 2024), these sources often lack information on socioeconomic variables and/or are cross-sectional.

Understanding the health burden of miscarriage is important, because it is a common experience and it can have consequences for population health. An increasing number of people postpone pregnancies until the last years of the reproductive life span. Since higher age at pregnancy is a risk factor for miscarriage, we can expect the number of miscarriages to increase. However, seeing those with older age at pregnancy as a homogenous vulnerable group with a high miscarriage risk without considering why some people postpone pregnancies, or how age intersects with socioeconomic characteristics, is unlikely to provide productive policy solutions. Since structural conditions influence both timing of pregnancy (Geronimus 2003) and the association between older age and various pregnancy and child outcomes (Goisis et al. 2017, Goisis et al. 2018), policy interventions should aim to tackle these conditions to provide individuals the possibility to time their pregnancies at the most suitable moment for them.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented in the Seminar series on Fertility and Vulnerability at the Centre for Research on Families and Relationships, University of Oxford in January 2023; and in the Quantitative Social Science Seminar at the University College London, UK in June 2022. The authors would like to thank the audiences and organisers of these events for their insightful feedback.

Funding

Heini Väisänen was funded by the European Union (ERC, SOC-MISC, grant number 101077594). Katherine Keenan was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Centre for Population Change Connecting Generations research programme, grant number ES/W002116/1. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency or the ESRC. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority nor the ESRC can be held responsible for them.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

Andersen, A.-M. N., Andersen, P. K., Olsen, J., Grønbæk, M., & Strandberg-Larsen, K. (2012) Moderate alcohol intake during pregnancy and risk of fetal death. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(2), 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr189

Antoniotti, G. S., Coughlan, M., Salamonsen, L. A., & Evans, J. (2018) Obesity associated advanced glycation end products within the human uterine cavity adversely impact endometrial function and embryo implantation competence. Human Reproduction, 33(4), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey029

Ashcraft, A., Fernández‐Val, I., & Lang, K. (2013) The consequences of teenage childbearing: consistent estimates when abortion makes miscarriage non‐random. The Economic Journal, 123(571), 875–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12005

Bardos, J., Hercz, D., Friedenthal, J., Missmer, S. A., & Williams, Z. (2015) A national survey on public perceptions of miscarriage. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 125(6), 1313–1320. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000859

Berrington, A., Stone J., & Beaujouan, E. (2015) Educational differences in timing and quantum of childbearing in Britain: A study of cohorts born 1940−1969. Demographic Research, 33(26), 733-764. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.33.26

Bommaraju, A., Kavanaugh, M. L., Hou, M. Y., & Bessett, D. (2016) Situating stigma in stratified reproduction: Abortion stigma and miscarriage stigma as barriers to reproductive healthcare. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 10, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2016.10.008

Bruckner, T. A., Mortensen, L. H., & Catalano, R. A. (2016) Spontaneous pregnancy loss in denmark following economic downturns. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(8), 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww003

Caserta, D., Ralli, E., Matteucci, E., Bordi, G., Soave, I., Marci, R., & Moscarini, F. (2015) The influence of socio-demographic factors on miscarriage incidence among italian and immigrant women: A critical analysis from Italy. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(3), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0005-z

Christian, L. M. (2012) Psychoneuroimmunology in pregnancy: Immune pathways linking stress with maternal health, adverse birth outcomes, and fetal development. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(1), 350–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.07.005

Christiansen, O. B., Steffensen, R., Nielsen, H. S., & Varming, K. (2008) Multifactorial etiology of recurrent miscarriage and its scientific and clinical implications. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation, 66(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1159/000149575

Cockerham, W. C., Rütten, A., & Abel, T. (1997) Conceptualizing contemporary health lifestyles: The Sociological Quarterly, 38(2), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1997.tb00480.x

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., & Baum, A. (2006) Socioeconomic status is associated with stress hormones. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(3), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000221236.37158.b9

de La Rochebrochard, E., & Thonneau, P. (2002) Paternal age and maternal age are risk factors for miscarriage: results of a multicentre European study. Human Reproduction, 17(6), 1649–1656. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/17.6.1649

Delabaere, A., Huchon, C., Deffieux, X., Beucher, G., Gallot, V., Nedellec, S., … & Lémery, D. (2014) Épidémiologie des pertes de grossesse. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction, 43(10), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.09.011

Di Nallo, A., & Köksal, S. (2023) Job loss during pregnancy and the risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. Human Reproduction, 38(11), 2259–2266. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dead183

ESHRE Early Pregnancy Guideline Development Group. (2017) Recurrent pregnancy loss (Version 2). European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. https://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Recurrent-pregnancy-loss

Farren, J., Jalmbrant, M., Falconieri, N., Mitchell-Jones, N., Bobdiwala, S., Al-Memar, M., … & Bourne, T. (2020) Posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression following miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy: A multicenter, prospective, cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 222(4), 367.e1-367.e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.10.102

Feodor Nilsson, S., Andersen, P. K., Strandberg-Larsen, K., & Nybo Andersen, A.-M. (2014) Risk factors for miscarriage from a prevention perspective: A nationwide follow-up study. BJOG, 121(11), 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12694

García-Enguídanos, A., Calle, M. E., Valero, J., Luna, S., & Domı́nguez-Rojas, V. (2002) Risk factors in miscarriage: A review. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 102(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00613-3

Geller, P. A., Kerns, D., & Klier, C. M. (2004) Anxiety following miscarriage and the subsequent pregnancy: A review of the literature and future directions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00042-4

Geronimus, A. T. (2003) Damned if you do: Culture, identity, privilege, and teenage childbearing in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 57(5), 881–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00456-2

Giakoumelou, S., Wheelhouse, N., Cuschieri, K., Entrican, G., Howie, S. E. M., & Horne, A. W. (2016) The role of infection in miscarriage. Human Reproduction Update, 22(1), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv041

Gissler, M., Rahkonen, O., Arntzen, A., Cnattingius, S., Andersen, A.-M. N., & Hemminki, E. (2009) Trends in socioeconomic differences in Finnish perinatal health 1991–2006. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(6), 420–425. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.079921

Goisis, A., Håberg, S. E., Hanevik, H. I., Magnus, M. C., & Kravdal, Ø. (2020) The demographics of assisted reproductive technology births in a Nordic country. Human Reproduction, 35(6), 1441–1450. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa055

Goisis, A., Schneider, D. C., & Myrskylä, M. (2017) The reversing association between advanced maternal age and child cognitive ability: Evidence from three UK birth cohorts. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(3), 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw354

Goisis, A., Schneider, D. C., & Myrskylä, M. (2018) Secular changes in the association between advanced maternal age and the risk of low birth weight: A cross-cohort comparison in the UK. Population Studies, 72(3), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2018.1442584

Gomez, A. M., Arteaga, S., & Freihart, B. (2021) Structural inequity and pregnancy desires in emerging adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(6), 2447–2458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01854-0

Greenwood, D. C., Alwan, N., Boylan, S., Cade, J. E., Charvill, J., Chipps, K. C., … & Wild, C. P. (2010) Caffeine intake during pregnancy, late miscarriage and stillbirth. European Journal of Epidemiology, 25(4), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9443-7

Ha, S., Ghimire, S., & Martinez, V. (2022) Outdoor air pollution and pregnancy loss: A review of recent literature. Current Epidemiology Reports, 9(4), 387–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-022-00304-w

Hardie, J. H., & Landale, N. S. (2013) Profiles of risk: maternal health, socioeconomic status, and child health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(3), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12021

Hegelund, E. R., Poulsen, G. J., & Mortensen, L. H. (2019) Educational attainment and pregnancy outcomes: A Danish register-based study of the influence of childhood social disadvantage on later socioeconomic disparities in induced abortion, spontaneous abortion, stillbirth and preterm delivery. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(6), 839–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-02704-1

Hein, A., Rauh, C., Engel, A., Häberle, L., Dammer, U., Voigt, F., … & Goecke, T. W. (2014) Socioeconomic status and depression during and after pregnancy in the Franconian Maternal Health Evaluation Studies (FRAMES). Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 289(4), 755–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-3046-y

James, J. E. (2021) Maternal caffeine consumption and pregnancy outcomes: A narrative review with implications for advice to mothers and mothers-to-be. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 26(3), 114–115. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111432

Jardine, J., Walker, K., Gurol-Urganci, I., Webster, K., Muller, P., Hawdon, J., … & Meulen, J. van der. (2021) Adverse pregnancy outcomes attributable to socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in England: A national cohort study. The Lancet, 398(10314), 1905–1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01595-6

Joseph, K. S., Liston, R. M., Dodds, L., Dahlgren, L., & Allen, A. C. (2007) Socioeconomic status and perinatal outcomes in a setting with universal access to essential health care services. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 177(6), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.061198

Julià, M., Pozo, O., Gómez-Gómez, A., & Bolíbar, M. (2020) Precarious employment and stress: Any differences between objective or subjective measures of stress? European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5), ckaa165.1352. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.1352

Jurkovic, D., Overton, C., & Bender-Atik, R. (2013) Diagnosis and management of first trimester miscarriage. BMJ, 346. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3676

Kakita-Kobayashi, M., Murata, H., Nishigaki, A., Hashimoto, Y., Komiya, S., Tsubokura, H., … & Okada, H. (2020) Thyroid hormone facilitates in vitro decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells via thyroid hormone receptors. Endocrinology, 161(6), bqaa049. https://doi.org/10.1210/endocr/bqaa049

Kneale, D., & Joshi, H. (2008) Postponement and childlessness: Evidence from two British cohorts. Demographic Research, 19, 1935–1968. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.58

Larsen, E. C., Christiansen, O. B., Kolte, A. M., & Macklon, N. (2013) New insights into mechanisms behind miscarriage. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-154

Lindberg, L., Kost, K., Maddow-Zimet, I., Desai, S., & Zolna, M. (2020) Abortion reporting in the United States: an assessment of three national fertility surveys. Demography, 57(3), 899-925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00886-4

Lindberg, L., & Scott, R. H. (2018) Effect of ACASI on reporting of abortion and other pregnancy outcomes in the US National Survey of Family Growth. Studies in Family Planning, 49(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12068

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995) Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958

Macmillan, R., & Shanahan, M. J. (2022) Explaining the occupational structure of depressive symptoms: precarious work and social marginality across European countries. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 63(3), 446–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465211072309

Maconochie, N., Doyle, P., Prior, S., & Simmons, R. (2007) Risk factors for first trimester miscarriage-results from a UK-population-based case-control study. BJOG, 114(2), 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01193.x

Magnus, M. C., Wilcox, A. J., Morken, N.-H., Weinberg, C. R., & Håberg, S. E. (2019) Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: Prospective register based study. BMJ, 364. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l869

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020) Health equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 years on. Institute of Health Equity.

McLean, S., & Boots, C. E. (2023) Obesity and miscarriage. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 41(03/04), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1777759

Morris, A., Meaney, S., Spillane, N., & O’Donoghue, K. (2015) The postnatal morbidity associated with second-trimester miscarriage. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 29(17), 2786–2790. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1103728

Mostafa, T., & Wiggins, D. (2014) Handling attrition and non-response in the 1970 British Cohort Study. CLS Working Papers 2014/2. Centre for Longitudinal Studies, University of London.

Nepomnaschy, P. A., Welch, K. B., McConnell, D. S., Low, B. S., Strassmann, B. I., & England, B. G. (2006) Cortisol levels and very early pregnancy loss in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(10), 3938–3942. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0511183103

Nguyen, B. T., Chang, E. J., & Bendikson, K. A. (2019) Advanced paternal age and the risk of spontaneous abortion: An analysis of the combined 2011–2013 and 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 221(5), 476.e1-476.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.028

Norsker, F. N., Espenhain, L., Rogvi, S. á, Morgen, C. S., Andersen, P. K., & Andersen, A.-M. N. (2012) Socioeconomic position and the risk of spontaneous abortion: A study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. BMJ Open, 2(3), e001077. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001077

Osborn, J. F., Cattaruzza, M. S., & Spinelli, A. (2000) Risk of spontaneous abortion in Italy, 1978–1995, and the effect of maternal age, gravidity, marital status, and education. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(1), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010128

Parazzini, F., Chatenoud, L., Tozzi, L., Benzi, G., Pino, D. D., & Fedele, L. (1997) Determinants of risk of spontaneous abortions in the first trimester of pregnancy. Epidemiology, 8(6), 681–683. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199710000-00012

Pineles, B. L., Park, E., & Samet, J. M. (2014) systematic review and meta-analysis of miscarriage and maternal exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179(7), 807–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt334

Qu, F., Wu, Y., Zhu, Y.-H., Barry, J., Ding, T., Baio, G., … & Hardiman, P. J. (2017) The association between psychological stress and miscarriage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01792-3

Quenby, S., Gallos, I. D., Dhillon-Smith, R. K., Podesek, M., Stephenson, M. D., Fisher, J., … & Coomarasamy, A. (2021) Miscarriage matters: The epidemiological, physical, psychological, and economic costs of early pregnancy loss. The Lancet, 397(10285), 1658–1667. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00682-6

San Lazaro Campillo, I., Meaney, S., O’Donoghue, K., & Corcoran, P. (2019) Miscarriage hospitalisations: A national population-based study of incidence and outcomes, 2005–2016. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0720-y

Temple, R., Aldridge, V., Greenwood, R., Heyburn, P., Sampson, M., & Stanley, K. (2002) Association between outcome of pregnancy and glycaemic control in early pregnancy in type 1 diabetes: ]Population based study. BMJ, 325(7375), 1275–1276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1275

University College London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & NatCen Social Research. (2024) National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. [data series]. 6th Release. UK Data Service. SN: 2000036. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-2000036

University College London, UCL Social Research Institute, Centre for Longitudinal Studies. (2024) 1970 British Cohort Study. [data series]. 11th Release. UK Data Service. SN: 200001. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-Series-200001

Väisänen, H., & Murphy, M. (2014) Social inequalities in teenage fertility outcomes: Childbearing and abortion trends of three birth cohorts in Finland. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46(2), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1363/46e1314

van den Berg, M. M. J., van Maarle, M. C., van Wely, M., & Goddijn, M. (2012) Genetics of early miscarriage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 1822(12), 1951–1959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.07.001

Watson, K., & Angelotta, C. (2022) The frequency of pregnancy recognition across the gestational spectrum and its consequences in the United States. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 54(2), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1363/psrh.12192

Wisborg, K., Kesmodel, U., Henriksen, T. B., Hedegaard, M., & Secher, N. J. (2003) A prospective study of maternal smoking and spontaneous abortion. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 82(10), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00244.x

[1] Pregnancy loss means all lost conceptions, but the focus here is on miscarriage, which is a pregnancy loss after a recognised pregnancy and before 24 weeks’ gestation (ESHRE Early Pregnancy Guideline Development Group 2017).

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 2 (2025), Issue 3 CC-BY