Continuity of biopolitics in late Soviet and post-Soviet Russia: What policy documents can tell us

Research Article

Olga Temina1*, Olga Zvonareva1, and Klasien Horstman1

1Department of Health, Ethics, and Society, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands *Corresponding author: Olga Temina, o.temina@maastrichtuniversity.nlFrom a critical public health perspective, public health serves as an instrument of biopolitics in modern societies. Through public health measures, citizens’ bodies are regularised to exhibit desirable characteristics. However, what is considered desirable differs between epochs and political configurations. In this article we aimed to discern what kinds of subjects were envisioned as ideal and what configurations of public health were consequently produced in the late Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia. Through the analysis of legislative documents that have regulated Russian public health since their first codification in 1971 until now, we traced transformations of the state’s biopolitical agenda. We demonstrate how the Soviet paternalistic state aimed to provide health(care) for all while coercing those who did not share its ideals of health. We show how the liberalisation and marketisation of the 1990s attempted to transform citizens into responsible patient-consumers, and how, nowadays, public health regulation balances neoliberal ideas of health and Soviet notions of control. ‘Reading off’ legislative documents highlights how public health is transformed in line with biopolitical agendas, which exist in continuity and are deeply rooted both in the agendas of the past and imaginaries of the future.

Introduction

In his analysis of the origins of the power of modern states, Foucault (1978) argued that human bodies and the ability to regulate and control them is a central feature of modern ‘Western’ states. This preoccupation with human bodies explains the rise of the disciplines of medicine and public health in the nineteenth century. Since then, according to Lupton (1995), ‘in contemporary Western societies they [medicine and public health] have replaced religion as the central institutions governing the conduct of human bodies’ (p. 10). Lupton further argues that public health is not value-free but is formed through discourses (re)produced by various actors – from the state to family – and in accordance with what these actors deem desirable in a ‘normal’ body. In Foucault’s terminology, Lupton argues that public health serves as an instrument of biopolitics, biopolitics being ways in which the biological characteristics of a population are regulated, controlled, policed, and sorted into what is defined as ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ and, hence, in need of correction. She argues that in ‘Western’ society, this normalcy often converges around ‘a certain kind of subject; a subject who is autonomous, directed at self-improvement, self-regulated, desirous of self-knowledge, a subject who is seeking happiness and healthiness’ (Lupton 1995, p. 11). As a result, public health aims to discipline its subjects into making healthy lifestyle choices and avoiding or minimising risks (Petersen & Lupton 1996).

This convergence, however, is not universal across time and space. The definitions of normalcy and abnormality, as well as the desirability of certain bodies and their characteristics, differ not only between epochs but also across different spaces and political configurations. Yet, most public health analysis through a biopolitical lens has focused on ‘Western’ societies. In this study, we aimed to discern what kind of subjects and, ergo, public health were sought to be produced in a different, non-democratic context, namely in Russia. We also aimed to trace the transformations of Russian biopolitics, expressed through public health configurations over time: from the late Soviet decades through the liberalisation and democratisation of the 1990s and early 2000s to the current regime solidification and crackdown. By focusing on the configurations of public health and biopolitics in a country with a significantly different political and economic history than those of the capitalist and democratic ‘West,’ we intend to broaden the perspectives of critical public health scholarship.

To trace these transformations, we engaged with the developments that were a part of Soviet and post-Soviet public health and healthcare legislation. We followed the tradition of material-semiotic analysis, according to which policy documents do not simply represent reality or appear in response to pre-existing problems; they have a capacity to formulate issues in specific ways, as well as to transform, bring to fore, or obscure them (Asdal & Reinertsen 2022). Such an approach allowed us to discern biopolitics in the making by seeing how citizens’ health was problematised, politicised, and policed at some times and de-problematised, de-politicised, and disregarded at other times. By focusing exclusively on public health documents and not on public health practices, we attempted to gain insight into the ideals hardwired in public health design rather than in circumstances that enabled or constrained the implementation of those ideals. Our focus on legislative, state-produced documents was stipulated by the overwhelming dominance of the state in the public health arena both during Soviet times and after the collapse of the USSR.

State, Biopolitics and Public Health

Although state is hardly the only actor of public health, as public health discourses are formulated by multiple institutions and social groups (Lupton 1995), the state is undoubtedly an important actor of biopolitics. Rose (2001) contends that at the beginning of the twentieth century, states exercised their biopolitical agency through two types of public health measures: hygienic and eugenic. The first attempted to promote the population’s health through sanitary measures and habits, while the second aimed to control the population’s reproduction, incentivising some categories of the population to procreate and disincentivising and preventing others from doing so. According to Rose, both hygienic and eugenic measures implemented by a state meant to enhance the fitness of a nation to make it more resistant to threats emanating from other nations. However, he contends that relationships between a contemporary state and its subjects have changed, and that the state is no longer expected to directly intervene in the name of health but to enable and facilitate the health of the population. As Petersen and Lupton (1996) explain, the proliferation of neoliberalism since the mid-1970s questioned the ability of the state to govern efficiently and emphasised the entrepreneurial potential of individuals operating within a free market. This has gradually shifted the responsibility of protecting one’s health from the state to the individuals themselves, leaving the state to guarantee citizens’ personal freedom while citizens are disciplined to engage in the self-governance of their bodies and manage their own health risks. Thus, according to Petersen and Lupton (1996), in contemporary neoliberal societies public health promotes normalisation of citizens into rational, autonomous, and self-disciplined consumers whose bodies bear evidence of consumption but also of self-discipline.

A turn towards the ‘new public health’ in the mid-70s with its focus on health promotion allowed for the penetration of public health into increasingly more spheres of human life (Lupton 1995). Developments in epidemiology and statistics allowed to render increasingly more situations and activities as ‘risky’ and increasingly more populations as ‘at risk’ (Lupton 2013, Petersen & Lupton 1996). Thus, risk became ‘a governmental strategy of regulatory power’ (Lupton 2013, p. 116) – by managing risks, citizens pursue their best interests while aligning their behaviour and bodies with what is considered desirable by the neoliberal state and society.

One of the aspects of human health that has solicited particular attention from states and public health professionals is reproduction. As Rabinow and Rose (2006) argue, reproduction connects ‘the individual and the collective’, making it a ‘biopolitical space par excellence’ (p. 208). Feminist scholarship has explored how matters of (female) bodies, such as fertility, pregnancy, menstruation, menopause, lactation, and birth, do not ‘simply’ belong to the sphere of biology and health but constitute an arena of power struggles and contestations that continuously re-shape what is normal and pathological (see Ginsburg & Rapp 1991; for a programmatic text, see Lupton 1994). The politics of reproduction are not only important to the regulation of private lives. In the case of Eastern European countries, Gal and Kligman (2000) demonstrate how reproduction becomes central to political processes and how debates over its control function as a structuring and moralising tactic for various political actors. The regulation of reproduction, even when framed as matters of health or rights, inevitably becomes linked to ‘nation-building and subject-making’ (Krause & De Zordo 2012, p. 140) and thus constitutes the very essence of biopolitics.

Biopolitics and Public Health in Studies of Russia

To date, Soviet and post-Soviet public health has hardly been studied through the lens of biopolitics. What is known is mostly based on historical studies of public health and healthcare systems in Russia.

The establishment of Soviet public health was rooted in the rise of social hygiene as an influential perspective on population health after the 1917 revolution (Solomon 1994). This perspective asserts that illness has to be approached not only as a biological but also as a social phenomenon affected by people’s living conditions, hygiene, work, leisure, etc. The public health system created after the revolution by social hygienist Nikolai Semashko emphasised, at least in theory, the importance of disease prevention and the availability of free medical care based on the population’s needs (Heinrich 2022). The healthcare system was highly centralised and operated by the state at all administrative levels. Despite not always being true to its initial claims of universality or dedication to prevention (Heinrich 2022, Zatravkin et al. 2020), current Russian public health still retains these principles. However, since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the system was reformed to adapt to radically changed economic realities, to address challenges of epidemiological transition and high mortality rates (Tulchinsky & Varavikova 1996), and to incorporate new ‘Western’ medical and public health practices and ideas. For example, a system of compulsory medical insurance (CMI) was designed to give healthcare organisations financial incentives to compete for customers (patients) by providing better healthcare services (Shishkin 2018). Other reforms were aimed at modernising the healthcare infrastructure and investing in care for patients with non-communicable diseases (Shishkin 2017). Despite these and other reforms, the Russian healthcare system remains underfunded, unequally distributed among the regions, and highly centralised, with most care provided by the public sector. However, the improvement of the economic situation in the 2000s allowed the state to invest in areas of public health that it deemed the most important. Matveev and Novkunskaya (2022) wrote that, as low birth rates were perceived as a disturbing demographic development, capital investments were made in maternity care and various programs aimed at incentivising women to give birth to more children. The pro-natalist character of these policies was hardly a recent development: despite the Soviet Union being the first country to legalise abortion and abortion being virtually the only (reliable) method of fertility control accessible to women, the Soviet state always pursued a pro-natalist agenda exercised through, among others, subjecting women to punitive treatment from medical personnel (Rivkin-Fish 2013).

Political scientists Makarychev and Medvedev (2015) draw attention to these pro-natalist initiatives and discourses as well as other public health measures, such as a ban on imports of some foreign foodstuffs and the reintroduction of physical fitness norms in schools. They argue that together with policies aimed at regulating citizens’ sexual orientation and banning the adoption of Russian children by American families, these initiatives contributed to the project of nation-(re)building initiated by the state, where a ‘traditional’ and conservative Russian national identity was imagined in contrast to a liberal identity of the ‘West’ (Makarychev & Medvedev 2015, Yatsyk 2019). However, these studies are not focused specifically on public health, and they are not taking the biopolitical angle. Our study expands this scholarship by addressing this gap.

Methodology

To trace the biopolitical developments in the envisioned ideal subjects and consequently produced public health in Russia over the last 50 years, we focused our attention on legislation as a space of state power operation. We drew from the tradition of material semiotic analysis, which treats documents (laws, policies, etc.) as actors entangled in complex relations with the people who produce and read them, with materialities that they were designed to regulate, and with broad societal issues topical to a particular time and context. Documents have the capacity to ‘establish agendas and format issues’ (Asdal & Reinertsen 2022, p. 104), thus framing something as deserving (or not) of public concern and attention and making possible one solution over another. When legislative documents are approached as actors entangled in social reality, a close reading of their texts allows us to discern the state’s biopolitical agendas and see what kinds of subjects are deemed desirable and what public health measures are imagined as possible to implement to achieve the ideal.

We focused our analysis on three documents that intended to regulate health-related issues in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia: the Soviet law ‘On health protection’ (O zdravoohranenii 1971) effective from 1971 within the territory of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), ‘The fundamentals of citizens’ health protection legislation of the Russian Federation’ (Osnovy 1993) that replaced it in 1993, and the contemporary Federal Law N323-FZ (Ob osnovah ohrany zdorovʹâ graždan 2011) effective from 2011 to present. Our selection of documents was driven by the importance they had or currently have for regulation of public health. Thus, ‘On health protection’ was the first instance of the codification and systematisation of health-related legislation in the RSFSR; prior to it, the functioning of public health had to rely on scattered decrees, regulations, and communist party programmes (Davydova 2015). In the legislation of 1993 (Osnovy 1993) and 2011 (Ob osnovah ohrany zdorovʹâ graždan 2011) the supremacy of these documents in the legal field of ‘health protection’ was explicitly stated and formalised. Although there are other federal laws pertaining to the issues of health (for example, laws regulating CMI, circulation of pharmaceuticals, sanitation, vaccination, tobacco smoking), it is Federal Law N323-FZ and its predecessors that contain specific legal definitions of what health is and how citizens (must) achieve it. Nevertheless, these documents have not been functioning independently but rather within a network of other laws, orders, and decrees that we also considered to provide better interpretations of the aspects that were drawn broadly in the main documents.

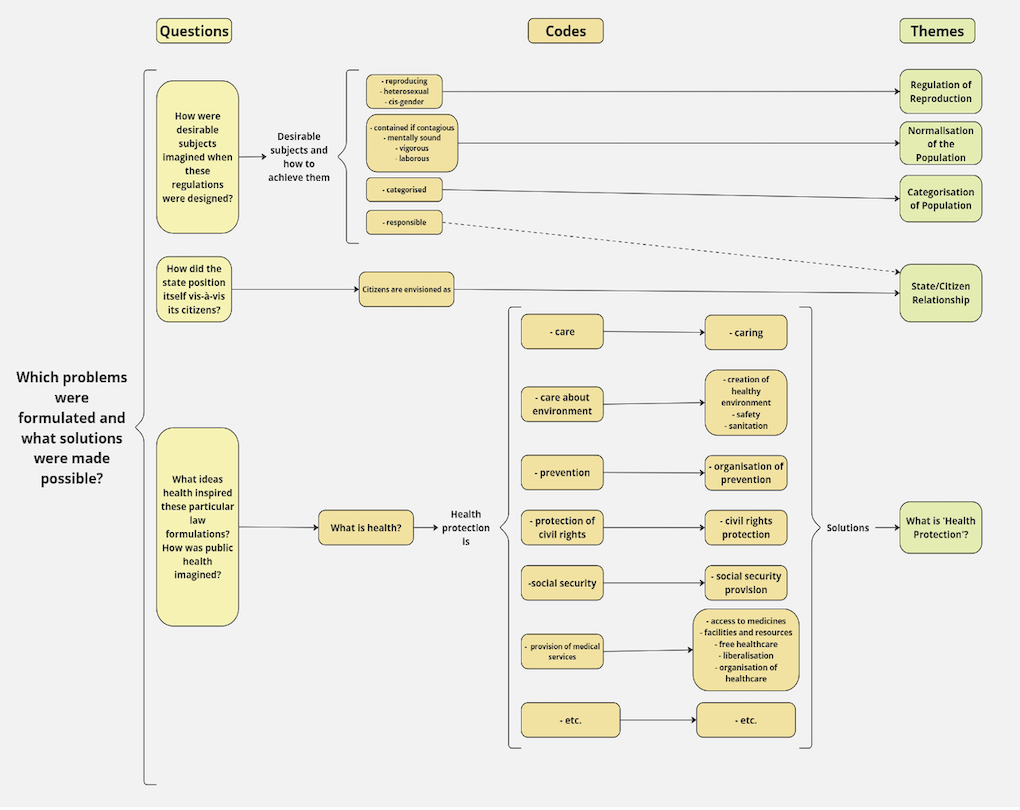

In our analysis, we followed the logic of Bacchi’s (2009) ‘what’s the problem represented to be’ (WPR) approach. This approach operates on the premise that problems do not exist independently of the policies that address them but that problems are constructed by the policies themselves. To ‘read off’ what these policies suggest to be the problem, what assumptions allow for such formulations of the problem, and what consequences particular formulations might have, Bacchi suggests to ‘ask’ the policies a set of questions. We adapted these questions to serve the purposes of our analysis. The list of the adapted questions is presented in Figure 1. In a close reading of the documents through the lens of these questions, OT developed a coding scheme in the Atlas.Ti software and coded the documents. The preliminary lines of the analysis were discussed with OZ and KH. Following this discussion, the coding scheme was fine-tuned, the connections between the codes were drawn, and five main themes were identified. In Figure 1, we delineate the connections among the questions that guided our reading of the documents, the coding scheme, and the emerged themes.

Figure 1: Alignment between questions, codes, and themes.

There are limitations to our approach. First, by focusing solely on three main legislative documents, we could not address some aspects and connotations that were likely present in other documents that regulated different health-related issues in more detail. Second, as ‘the state’ is not a monolithic entity with well-defined interests but rather a network of actors with different stakes who continuously interact with each other to work on laws and policies, our choice of documents did not allow us to see visions of public health produced by certain actors, such as regional governments or certain ministries. Third, attention to the text of the legislative documents, as opposed to an analysis of their creation or implementation, did not allow to reveal how biopolitical agendas are negotiated or acted upon. However, our analysis brought to the fore ideas that dominated Russian Soviet and post-Soviet public health and the ways that the state’s ideals about its citizens’ bodies were translated into specific public health measures.

Results

In the presentation of the results, we follow the timeline of the documents. However, it is the themes recurrently encountered throughout the documents that are at the centre of our analysis. In each document, we focus on how health protection is imagined, what state’s ideal subjects look like, and how the relationships between the state and its citizens are configured. Notably, in each of the analysed documents significantly more space is allocated to regulation of reproductive bodies especially when compared with space allocated to, for example, disabled or ageing ones. Following the documents’ logic, we discuss meanings produced by this focus and regulations themselves. The recurrence of themes allows us to trace the historical (dis)continuity of biopolitical processes, to see where they originate and how they change. As the desirable biopolitical subjects transform, public health and biopolitical mechanisms transforms with them.

Soviet Legislation: Reproduction of the Productive and Vigorous (1971)

We begin with the analysis of the healthcare legislation effective in the RSFSR since 1971 – ‘On health protection’ (O zdravoohranenii 1971). The preface of ‘On health protection’, as well as the further text, show two key characteristics of this document: a very broad definition of what constitutes ‘protecting the health of the people’ and a paternalistic approach of the state vis-a-vis its citizens in issues related to their health (again, broadly understood). In other words, this document articulated the state as an agent that had full power over the decisions that affected its citizens’ health.

What is ‘Health Protection’?

The Soviet ‘health protection’ legislation covered life domains that spanned far beyond the provision of medical services: it covered the development of medical science; preventative measures; care for urban, living, leisure and work environments and nature; provision of social security; and work safety. This is clear from such articles as: Article 24 (‘Sanitary requirements for the planning and development of populated areas’), Article 28 (‘Provision of additional living space to persons suffering from severe forms of certain chronic diseases’), and Article 31 (‘Prevention and elimination of noise’). This framing of Soviet citizens’ health entailed that health was situated not solely within their bodies but also within their (social) environments, thus allowing for intervention in these areas in the name of health.

Normalisation of the Population

Interestingly, the broad definition of health protection also allowed for physical and moral segregation. The document enacted protection of health by forcing treatments on people with tuberculosis, leprosy, mental health disorders, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and alcohol and drug addictions. These people were subjected to obligatory treatments, and if their behaviour was deemed dangerous for the public or did not align with the expectations of correction and (moral) improvement, they were forced into involuntary hospital admission, confinement, or treatment with labour (Articles 55–59.1). Previous research demonstrates that the Soviet state framed these conditions not so much in medical but in moral terms. For example, Lipša (2019) and Raikhel (2016) studied how the treatment of people with addictions and STIs was designed first and foremost to punish and correct their antisocial, supposedly anti-Soviet behaviour through practices of isolation and shame. Although tuberculosis was regarded differently – as a devastating consequence of exploitative capitalism – people who spread the disease, either knowingly or not, were also portrayed as deserving punishment rather than care (Polianski & Kosenko 2021). Mental disorder was used as a pretext to punish and incarcerate political dissidents, the official reasoning being that the opposition to the communist ideology was a sign of an inability to reason (Luty 2014, Reich 2014). Through establishing coercive public health measures towards people with these conditions, the law conveyed that it was the person and not the disease that should have been treated in the first place. The legislation maintained the moral interpretations of these diseases, and while it set to treat, it also aimed to correct, to separate ‘the healthy’ from ‘the sick’, and to normalise the subjects into healthy, ideologically sound, mentally vigorous Soviet population.

State/Citizen Relationship

The coercive treatment of populations with STIs, addictions, mental health disorders, and other conditions was possible because the ‘On health protection’ law did not frame citizens and the state as equals – the state was enacted as a caretaker who must protect the health of its wards. Under this paternalistic approach, free-at-the-point-of-service healthcare and extensive social security measures became not only imaginable but indispensable. However, at the same time it allowed the state to make health decisions for its citizens. For example, Article 65 forbade women to do jobs that were ‘heavy and harmful for health’. Article 85 defined which jobs were accessible for disabled people. The paternalism subjected ‘bacillicarriers of infectious diseases’ to ‘recuperation’ (Article 40) and allowed the breach of medical confidentiality ‘in the interest of the population’s health protection’ (Article 19) and whenever investigation or a court requested it. ‘On health protection’ enacted a citizen as someone who was unlikely to make the right health decisions on their own because of ignorance, foolishness, or malintent. Thus, the decision must have been made for a citizen – their body controlled for their own benefit.

Regulation of Reproduction

Interestingly, in one case, the protection of health was formulated as a right of citizens to make a choice. Women were ‘granted the right’ to make a ‘decision about motherhood’ (Article 66). However, the legislative document did not enact women as autonomous subjects making decisions about their bodies. Instead, it enacted a pronatalist agenda, as the article that allowed abortion, Article 66, came under Section V (‘Protection of motherhood and childhood’). This section started with the passage ‘Motherhood in RSFSR is protected and encouraged by the state’, inscribing in the law the moral expectation that Soviet women choose to become mothers at some point of their lives, and when they do, they are provided with special (medical) treatment and social benefits. Thus, the Soviet women as described in this law were free to make any reproductive choice, but only one choice was supported by the state.

‘On health protection’ (O zdravoohranenii 1971) worked to regulate the lives of Soviet citizens in the name of their health, often invoking direct control and intervention for the ‘greater good’ of the population. The ‘greater good’ was imagined as reproduction of productive, ideologically pure citizens who were ready to work for the advancement of the state, and if they did, they could expect to be cared for in return.

The First Russian Healthcare Legislation after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union: In Between the Past and the Future (1993)

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Soviet healthcare legislation continued to be in effect for other two years, until the new law was adopted – ‘The fundamentals of citizens’ health protection legislation of the Russian Federation dated 22 July 1993 N5487-1’ (Osnovy 1993). To see how the newly formed state abandoned some old biopolitical undertakings, continued others, and introduced the new ones, we mostly focused on the very first edition of the document.

What is ‘Health Protection’?

With the retreat of communist ideology, the meaning of ‘health protection’ also changed. While it was still declared to include care for work and leisure environments, provision of social security, preventative measures, etc., the document did not allocate these issues any significant space – there were simply no articles in ‘The fundamentals…’ that regulated these life domains. The spheres of life that used to be under the direct state gaze during the Soviet times were no longer framed explicitly as concerning health protection. In line with the neoliberal ideas driving the economic reforms of the time, health was reformulated as the personal responsibility of an individual rather than the responsibility of the state.

State/Citizen Relationship

‘The fundamentals…’ also reflected two other developments of the time: the integration of human and civil rights in the legislation and a sharp transition to a market economy and the subsequent economic crisis. These developments introduced principles and concepts previously unknown to the health protection regulation in Russia, such as an equal right of health protection for everyone, prohibition of discrimination based on diagnosis (Article 17), patients’ rights (Article 30), informed consent (Article 32), the right to refuse medical intervention (Article 33), and the right to information about one’s own health (Article 31) and health-affecting factors (Article 19). The law established the first ethical committees (Article 16), explicitly guaranteed the provision of healthcare to convicts (Article 29), forbade forced organ donations (Article 47), and detailed rules of medical confidentiality and under what circumstances they could be breached (Article 61).

The document took the first steps in transforming the population from subjects of ‘health protection’ into patients with rights and choices. Through this transformation, the 1993 law differentiated itself from Soviet collectivity-centred legislation and adapted to liberal ideals by placing the individual at the centre of its regulation. Following the logic of individual choice in a free market and the moral notion of equalising the relationship between citizens and the state, the reforms of the time attempted to re-render ‘ignorant’ and ‘obedient’ patients into knowledgeable and cautious patient-consumers.

However, the focus on human and civil rights in the ‘The fundamentals…’ did not instantaneously reconfigure patient–state relationships, nor did it signify a loss of the state’s interest in regularising the body of the population. For example, Article 34 (‘Healthcare provision without citizen’s consent’) reserved the right of the state to confine and involuntarily treat those whose diagnosis was deemed socially dangerous, those who suffered from severe mental disorders, and those who committed socially dangerous acts. The idea of separating and normalising subjects that deviated from the norm by subjecting them to medical interventions or involuntary hospitalisations was transferred into the new legislation.

Regulation of Reproduction

The contradiction between the patronising Soviet approach to the state’s subjects and the neoliberal approach to them as individual consumers was also visible in the regulation of reproduction. On the one hand, ‘The fundamentals…’ did not construct a woman as an eventual mother and expanded the social criteria for abortion until the twenty-second week of gestation (Ob utverždenii perečnâ socialʹnyh pokazanij 1996). On the other hand, the law (Osnovy 1993) forbade voluntary sterilisation for people with fewer than two children or younger than 35 years old (Article 37) and emphasised that ‘every woman of childbearing age has a right for artificial insemination and embryo implantation’ (Article 35). Such ambiguity reflected the heated political debates about reproduction in the 1990s, described by researchers (e.g. Rivkin-Fish 2013, Temkina 2015) as ranging from discourses on women’s rights to discourses on nation’s extinction. With a conservative agenda eventually outweighing a liberal one, the list of social and medical criteria for abortion were shortened in 2003 and 2007, respectively. The benefit program ‘Maternity Capital’ that awarded financial support to women having second and subsequent children solidified this pro-natalist turn in 2007 (O dopolnitelʹnyh merah gosudarstvennoj podderžki semej, imejuŝih detej 2006). Thus, regulation of reproduction within ‘The fundamentals…’ represented a space of political contestation where old and new biopolitical agendas were being detangled, recombined, and reassembled.

Categorisation of the Population

‘The fundamentals…’ also reflected economic changes necessitated by the marketisation of the Russian economy. In the circumstances of the economic crisis and severe underfunding of healthcare (Twigg 1998), maintaining comprehensive and free healthcare services for all citizens was impossible. To address this problem, the legislation singled out certain population groups and underscored their rights to receive free medical services (Articles 22–24, 26–28, and 41–42). Thus, even though the law did not explicitly give any preferential treatment to these groups (pregnant women, mothers, children, elders, disabled, disaster survivors, residents of ecologically disadvantaged areas, people with socially significant diseases, and people with diseases posing a threat to the public), it prioritised their needs by additionally articulating their rights. Through this categorisation, the law constructed certain groups as more deserving of medical help by deciding ‘who shall live what sort of life and for how long’ (Fassin 2009, p. 53). The choice of groups that were prioritised demonstrated that biopolitical concerns had not changed significantly since the Soviet era, with fertility rates and the contagion of the population body staying at its core.

‘The fundamentals…’ (Osnovy 1993) articulated the ideals of the newly emerged market economy but also the welfare promises rooted in the Soviet past. It pictured a system in a phase of transformation, enacting biopolitical agendas both from the past (e.g. elements of pro-natalism and involuntary treatment of non-normalised subjects) and from the future as it was envisioned at that moment (e.g. patient-consumers, enjoying human and civil rights and free to make independent choices about their bodies). As the 2000s marked the (re)turn towards centralisation of power and conservatism, the envisioned futures changed and ‘The fundamentals…’ became obsolete.

Contemporary Healthcare Legislation: Neoliberal and Statist Logics (2011)

New healthcare legislation in Russia was adopted in 2011 against the backdrop of a national project, ‘Health’, launched in 2006 with the main goal of tackling what was perceived as the country’s demographic crisis. Healthcare reforms and direct investments in the healthcare system were aimed at decreasing mortality in the working-age population and increasing fertility rates, among other things. The document under analysis – ‘On fundamentals of health protection of citizens in the Russian Federation’ (Ob osnovah ohrany zdorovʹâ graždan 2011) – clearly shows the intensification of the state’s interest in health(care) as it became regulated in much greater detail than ever before. To see how biopolitics are currently enacted in this document, we analyse the most recent edition at the time of writing.

What is ‘Health Protection’?

The law sets to regulate citizens’ health mainly in the sphere of medical services provision. It continues to define free-at-the-point-of-service healthcare as a crucial component of health protection, and creates an assemblage of regulations that specify which services in what quantities must be provided to whom, in addition to when, where, and how they must be provided, and how this must be monitored. Through unprecedented attention to healthcare services provision, the document follows the trend set by ‘The fundamentals…’ and gravitates towards defining health protection as a tangible and measurable aim, such as sufficient hospital equipment or standardised medical interventions, rather than as something broad and overarching as a healthy environment or leisure.

Categorisation of the Population

In pursuit of these tangible results, the contemporary document strives to efficiently allocate limited resources by extending and solidifying the population categorisation introduced in ‘The fundamentals…’. Conceptually similar to its predecessor, the new document highlights that pregnant women, children (Articles 7, 52, and 54), people with socially significant diseases, and people with diseases posing a threat to the public (Article 43) have a right to receive all the necessary healthcare services. For army personnel (Article 25); athletes (Article 83, par. 6.2); state authorities and bureaucrats (Article 83, par. 6.1); and some other the law specifies from which budget – federal, regional, or ministerial – these groups’ needs must be covered. As previous research (Shishkin 2013) demonstrates that the federal budget is a more reliable source of healthcare financing than the regional one, we conclude that the legislation covertly prioritises those groups of the population whose healthcare needs are covered by it, without violating its own principle that ‘the state provides citizens with health protection irrespective of their gender, race, age, […] official capacity, […], etc.’ (Article 5). Through this subtle mechanism, the law enacts both old (bio)political priorities, such as attention to reproduction, and (relatively) recent ones, such as a focus on strengthening the army and the machinery of the state.

State/Citizen Relationship

The way citizens are enacted in the document is also characterised by similar ambiguity. On the one hand, as the law pays close attention to regulating healthcare service provision, it often enacts citizens as patients that, like in the Fundamentals (Osnovy 1993), are prompted to be proactive consumers who have right to choose a medical organisation and doctors (Article 21) and a right to receive accessible information about their health (Article 22). The current law also confirms and expands the rights established by its predecessor. For example, Article 20 (‘Informed voluntary consent to medical intervention and refusal of medical intervention’) states that citizens have a right to be informed in an accessible way about medical interventions offered to them and that such interventions cannot take place unless they consent to it.

On the other hand, the same article specifies that for groups within the population, such as people with diseases posing a threat to the public, people with severe mental illnesses, people under forensic investigation, and perpetrators, a medical intervention can be applied without their informed voluntary consent, and the decisions about such interventions are in the hands of doctors or the courts. The same occurs in Article 13 (‘Medical confidentiality’). It confirms the citizens’ rights to privacy of their medical information; at the same time, it delineates the population groups who cannot enjoy such privacy (e.g. people obligated to undergo drug addiction treatment) and situations when privacy can be breached (in the case of a threat of the spread of infectious diseases, for military medical examinations, for information exchange between medical organisations, for ‘accounting and control in the system of compulsory social security’, for quality and safety control, and some other situations). Thus, the old Soviet labelling of people with addictions, STIs, mental disorders, etc. as ‘abnormal’ and the separation of these groups from the ‘healthy’ population are again enacted in the legislation, but this is concealed within the articles establishing the citizens’ rights and not within the ones limiting them.

Regulation of Reproduction

With the eventual establishment of the pro-natalist agenda in official rhetoric starting in the 2000s, the new law began to lean heavily towards framing inevitable motherhood for every woman as a natural solution to what was perceived as demographic decline. The document brought back Soviet-style wording, ‘Motherhood in the Russian Federation is protected and encouraged by the state’ (Article 52). Unlike ‘The fundamentals…’, the new law does not aim to regulate family planning but to ‘protect health of mother and child’ and to solve ‘the questions of family and reproductive health’ (Chapter 6). The document enacts traditional gender and family roles for women and men: while the former have a right to access assisted-reproductive technologies and use services of surrogate mothers, whether they have (male) partners or not, the latter do not have such rights (Article 55). Thus, parenthood is rendered as a primal role for women, while for men it is only adjacent to their family status. The same regulation implicitly restricts access to reproductive technologies for non-heterosexual couples, thus enacting such families as invalid and their parenthood as unimaginable.

Despite these pro-natalist narratives, the law retains the right of every woman to make a ‘decision about motherhood’, in other words, to abort a pregnancy up until the twelfth week of gestation (Article 56). The decision to abort, however, is framed as unreasonable and rushed: any woman who makes it must wait from 48 hours to one week, depending on the term, before the procedure can take place. The social criteria for abortion up until the twenty-second week are reduced to delegitimise any reason to abort except one – rape (O socialʹnom pokazanii 2012). In addition, the regulation of circulation of pharmaceuticals for medication-induced abortion and morning-after pills is toughened (Ob utverždenii perečnâ lekarstvennyh sredstv 2023).

With the rise of nationalism in recent years, matters of reproduction have also become equated with matters of the nation and its security. The document limits the use of the services of surrogate mothers to only Russian citizens (Article 55), equating the ability to bear children to a strategically important resource that cannot be used for advancing the population of other nations. In 2020, the ‘Maternity Capital’ program, initially introduced to encourage birth of the second and consecutive children, was broadened to remunerate women for the birth of the first child as well (O dopolnitelʹnyh merah gosudarstvennoj podderžki semej, imejuŝih detej 2006). As a result, the conservative reproduction and gender politics, nationalism, and explicit pro-natalism of the legislation reinforce each other, reviving and enhancing the paternalistic relationships between citizens and the state.

Thus, the law attempts to maintain the population as citizens with human and civil rights while at the same time (re)establishing control over their bodies. Inherited from ‘The fundamentals…’, the enactment of citizens as patient-consumers capable of making reasonable decisions has been interrupted by a strong resurgence of the state as a normalising and controlling agent. This transformation is in line with the contradictions characteristic of the Russian welfare system, noted by other researchers (Matveev & Novkunskaya 2022) who argue that the neoliberal logics adopted in the 1990s co-exist with the statist logics of direct interventions inherited from the Soviet Union and re-actualised in the mid-2000s.

Conclusion

Through a material-semiotic analysis of public health legislation, we traced changes in the configurations of public health and developments in biopolitical processes in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia over the last fifty years. Our analysis, unsurprisingly, demonstrated an unwavering interest of the state in its citizens’ bodies – their reproduction and maintenance of their vigour and health. Of greater interest were the different configurations of public health invoked in the analysed documents. In Soviet legislation, the law puts the state in the position of a caretaker that had a responsibility to provide all that was necessary for health, which was understood broadly. The legislation of the 1990s and 2000s attempted to position citizens as consumers within the market of health services but at the same time did not fully relieve the state of its role as an overbearing provider. The current law continues further down this path by imagining public health as a result of both the consumption of health services by patients and the provision of free-at-the-point-of-service healthcare by the state.

Our results show that these changes in public health configurations were deeply tied to the ways in which the state envisioned its desirable subjects and the mechanisms of biopolitics it considered acceptable. In the legislation of the Soviet era, it was healthy, hardworking, and ideologically pure communist youth who guaranteed the country its imagined future. In exchange for providing health(services), the state expected citizens to comply with this ideal or face the consequences, often realised through some form of coercion. The Russian legislation during the transition period inherited this Soviet outlook on deviating subjects but imagined citizens’ abilities to make independent and informed choices as a way towards a healthy nation. It attempted to offset the power imbalance between the state and the citizens by emphasising the latters’ rights, but, at the same time, it retained the state’s right of coercion when subjects deviated too much from the desired image. In the current legislation, the imagery of the desired subjects is fuelled by the imaginaries of the past – as in the 1990s, citizens are envisioned as patient-consumers, operating rationally on a free market, but also, much like in Soviet times, they are not entirely trusted to make the right choices and thus are subjected to control and normalisation.

Legal documents lie at the very heart of the state’s functioning, and taking their agency seriously allowed for the exploration of (dis)continuities in the state’s biopolitical agendas. One of the most prominent continuities that we traced was the regulation of reproduction. Our analysis exposes striking similarities between the biopolitical agendas of the past Soviet and the current Russian states. In line with previous findings of feminist scholars (e.g. Temkina 2015), we see how women’s bodies are once again constructed as primarily childbearing and thus requiring special (medical) attention. In our study we demonstrated how law establishes the heterosexual multi-child family with traditional gender roles as the only subject desired by the state. These developments align with Makarychev and Medvedev’s (2015) argument about the construction of increasingly conservative reproduction and sexuality politics that are juxtaposed against the liberal biopolitics of the ‘West’. Against the backdrop of the ongoing Russian aggression in Ukraine, the Russian biopolitical agenda resembles not only the one adopted by the late Soviet Union but also the one of the Stalinist era, with its imposition of a ‘traditional’ family model for the purposes of mobilisation for warfare and industrial production (Hoffmann 2000).

When approached as actors embedded in the networks of material and non-material objects, the documents and ideas they construct cannot be separated from the broader contexts in which they come into being (Asdal & Reinertsen 2022). These contexts explain the differences and similarities between desirable subjects and possible public health solutions imagined in Russia and the ‘West’. Although both communist and capitalist states strived to shape their citizens according to the dominant ideas of the time through public health measures, in the USSR the state was an actor that dominated the public life and hardly allowed any deviations from the official communist ideals. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the marketisation and economic (neo)liberalisation that followed enabled the proliferation of other, ‘Western’ ideas. Nevertheless, while some aspects of the imagery of a ‘good’ Russian citizen were affected by the new neoliberal logic, others remained (almost) intact. Thus, post-Soviet Russian citizens were envisioned as consumers but, unlike in the ‘West’, their ability to exercise self-control and avoid risks was not imagined as central. On the one hand, Russian citizens were framed as rational actors who made their own health-related choices when it came, for example, to choosing healthcare providers or doctors. On the other hand, they remained rendered unreasonable or incapable when it came to reproductive decisions or mental illnesses. This also affected the allocation of responsibility in the envisioned public health system. While aiming to follow through with neoliberal logic and enact citizens as responsible for their own health, the legislation could not completely forsake the Soviet legacy of the state being the provider and protector of health and the supreme arbiter of normalcy of citizens’ bodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express gratitude to their colleagues from the Department of Health, Ethics, and Society for their invaluable comments, suggestions, and inspiring ideas. Moreover, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments allowed to significantly improve this paper.

Funding

This work was conducted within the ITN “MARKETS” funded by EU-Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions grant (Horizon 2020; grant agreement no: 861034). Any views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of any institution or funding body.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ORCiD IDs

Olga Temina https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3845-4318

Olga Zvonareva https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5548-7491

Klasien Horstman https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4048-4110

References

Asdal, K., & Reinertsen, H. (2022) Doing document analysis: A practice-oriented method. Sage.

Bacchi, C. L. (2009) Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be? Pearson.

Davydova, T. V. (2015) Soviet legislation on healthcare in the pre-war period (1917–1941): Historical and legal aspect. Tambov University Review. Series: Humanities 20, 11(151), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.20310/1810-0201-2015-20-11(151)-79-85

Fassin, D. (2009) Another politics of life is possible. Theory, Culture & Society, 26(5), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409106349

Foucault, M. (1978) The history of sexuality. Vol. 1: An introduction (R. Hurley, Trans.). Pantheon.

Gal, S., & Kligman, G. (2000) The politics of gender after socialism: A comparative-historical essay. Princeton University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.04390

Ginsburg, F., & Rapp, R. (1991) The politics of reproduction. Annual Review of Anthropology, 20, 311–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.001523

Heinrich, A. (2022) The emergence of the socialist healthcare model after the First World War. In F. Nullmeier, D. González de Reufels, & H. Obinger (Eds.), International impacts on social policy: Short histories in global perspective (pp. 35–46). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86645-7_4

Hoffmann, D. L. (2000) Mothers in the motherland: Stalinist pronatalism in its pan-European context. Journal of Social History, 34(1), 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2000.0108

Krause, E. L., & De Zordo, S. (2012) Introduction. Ethnography and biopolitics: Tracing “rationalities” of reproduction across the north–south divide. Anthropology & Medicine, 19(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2012.675050

Lipša, I. (2019) Categorized Soviet citizens in the context of the policy of fighting venereal disease in the Soviet Latvia from Khrushchev to Gorbachev (1955–1985). Acta Medico-Historica Rigensia, 12, 92–122. https://doi.org/10.25143/amhr.2019.XII.04

Lupton, D. (1994) Medicine as culture: Illness, disease, and the body in Western societies. Sage.

Lupton, D. (1995) The imperative of health: Public health and the regulated body. Sage.

Lupton, D. (2013) Risk (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Luty, J. (2014) Psychiatry and the dark side: Eugenics, Nazi, and Soviet psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.112.010330

Makarychev, A., & Medvedev, S. (2015) Biopolitics and power in Putin’s Russia. Problems of Post-Communism, 62(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1002340

Matveev, I., & Novkunskaya, A. (2022) Welfare restructuring in Russia since 2012: National trends and evidence from the regions. Europe–Asia Studies, 74(1), 50–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2020.1826907

O dopolnitelʹnyh merah gosudarstvennoj podderžki semej, imejuŝih detej [On additional measures of state support for families with children] (2006) Federalʹnyj zakon ot 29.12.2006 N 256-FZ [Federal Law dated 29.12.2006 N 256-FZ].

O socialʹnom pokazanii dlâ iskusstvennogo preryvaniâ beremennosti [On social criterion for artificial termination of pregnancy] (2012) Postanovlenie Pravitelʹstva Rossijskoj Federacii ot 06.02.2012 N 98 [Regulations of the Government of the Russian Federation dated February 6, 2012 N 98].

O zdravoohranenii [On health protection] (1971) Zakon RSFSR ot 29.07.1971 [RSFSR Law dated 29.07.1971].

Ob osnovah ohrany zdorovʹâ graždan v Rossijskoj Federacii [On fundamentals of health protection of citizens in the Russian Federation] (2011) Federalʹnyj zakon ot 21.11.2011 N 323-FZ [Federal Law dated 21.11.2011 N323-FZ].

Ob utverždenii perečnâ lekarstvennyh sredstv dlâ medicinskogo primeneniâ, podležaŝih predmetno-količestvennomu učetu [On authorisation of the list of pharmaceuticals for medical use that are subject to strict record keeping and storage] (2023) Prikaz Ministerstva zdravoohraneniâ Rossijskoj Federacii ot 01.09.2023 № 459n [Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation dated 01.09.2023 No. 459n].

Ob utverždenii perečnâ socialʹnyh pokazanij dlâ iskusstvennogo preryvaniâ beremennosti [On approval of the list of social criteria for artificial termination of pregnancy] (1996) Postanovlenie Pravitelʹstva Rossijskoj Federacii ot 08.05.1996 N 567 [Regulations of the Government of the Russian Federation dated May 8, 1996 N 567].

Osnovy zakonodatelʹstva Rossijskoj Federacii ob ohrane zdorovʹâ graždan ot 22 iûlâ 1993 goda N 5487-1 [The fundamentals of citizens’ health protection legislation of the Russian Federation dated 22 July 1993 N5487-1]. (1993).

Petersen, A., & Lupton, D. (1996) The new public health: Health and self in the age of risk. Sage Publications.

Polianski, I. J., & Kosenko, O. (2021) The “proletarian disease” on stage. Theatrical anti-tuberculosis propaganda in the early Soviet Union. Microbes and Infection, 23(8), 104838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2021.104838

Rabinow, P., & Rose, N. (2006) Biopower today. BioSocieties, 1(2), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855206040014

Raikhel, E. (2016) Governing habits: Treating alcoholism in the post-Soviet clinic. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7298/b2kv-m874

Reich, R. (2014) Inside the psychiatric word: Diagnosis and self-definition in the late Soviet period. Slavic Review, 73(3), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.5612/slavicreview.73.3.563

Rivkin-Fish, M. (2013) Conceptualizing feminist strategies for Russian reproductive politics: Abortion, surrogate motherhood, and family support after socialism. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(3), 569–593. https://doi.org/10.1086/668606

Rose, N. (2001) The politics of life itself. Theory, Culture & Society, 18(6), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632760122052020

Shishkin, S. (2013) Russia’s health care system: Difficult path of reform. In M. Alexeev & S. Weber (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the Russian economy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199759927.013.0025

Shishkin, S. (2017) How history shaped the health system in Russia. The Lancet, 390(10102), 1612–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32339-5

Shishkin, S. (2018) Health care. In I. Studin (Ed.), Russia: Strategy, policy and administration (pp. 229–239). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56671-3_21

Solomon, S. G. (1994) The expert and the state in Russian public health: Continuities and changes across the revolutionary divide. In D. Porter (Ed.), The history of public health and the modern state. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004418363_007

Temkina, A. (2015) The gynaecologist’s gaze: The inconsistent medicalisation of contraception in contemporary Russia. Europe–Asia Studies, 67(10), 1527–1546. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2015.1100371

Tulchinsky, T. H., & Varavikova, E. A. (1996) Addressing the epidemiologic transition in the former Soviet Union: Strategies for health system and public health reform in Russia. American Journal of Public Health, 86(3), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.86.3.313

Twigg, J. L. (1998) Balancing the state and the market: Russia’s adoption of obligatory medical insurance. Europe–Asia Studies, 50(4), 583–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668139808412555

Yatsyk, A. (2019) Biopolitical conservatism in Europe and beyond: The cases of identity-making projects in Poland and Russia. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 27(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2019.1651699

Zatravkin, S., Vishlenkova, E., & Sherstneva, E. (2020) “A radical turn”: The reform of the Soviet system of public healthcare. Quaestio Rossica, 8(2), 652–666. https://doi.org/10.15826/qr.2020.2.486

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 3 (2026), Issue 2 CC-BY-NC-ND