Between coercion, conditionality and abandonment: A descriptive analysis of English mental health spending and provision under austerity

Research Paper

Ed Kiely1*

1School of Geography, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK *corresponding author: ed.kiely@qmul.ac.ukWhile critical scholarship has demonstrated the harmful effects of austerity on public mental health, relatively little attention has been paid to the impact of austerity on health services themselves. In response, this paper develops a descriptive analysis of mental health spending and provision in England during the austerity period, from 2009–10 to 2019–20. It examines spending patterns at the national and local level, highlighting both reductions and increases that have been overlooked by prior research. In a context of wider public spending retrenchment, the paper argues that the divergent impacts on localities revealed by this analysis are best understood as multiple ‘localised austerities’. The paper then interrogates national trends in mental health provisioning, utilisation and treatment, finding that the overall mental health service landscape under austerity is characterised by three trends which have the potential to harm public health. Inpatient services are utilising more coercion; community services are increasingly conditionalised; and a significant population – too ill for work but judged too healthy for treatment – has been abandoned by services. For critical scholars and practitioners of public health, these findings highlight the complexity of the political, economic and institutional dynamics which distribute spending cuts and therefore mediate the effects of austerity on health.

Introduction

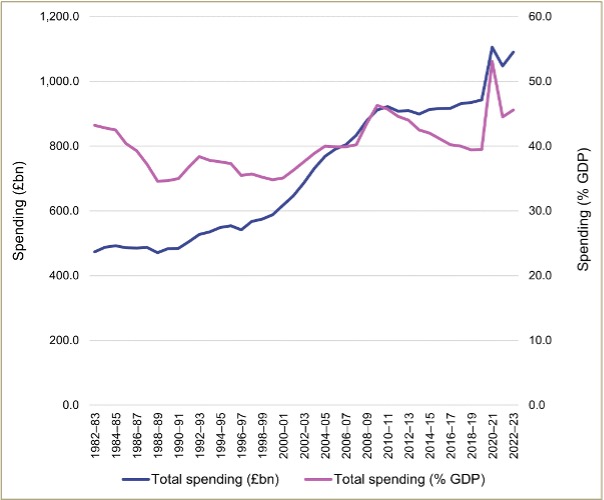

Beginning in 2010, the UK’s newly elected Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government rolled out austerity – ‘the policy of cutting the state’s budget to promote growth’ (Blyth 2013, p. 2) – across England (Gray & Barford 2018). This policy continued under the subsequent Conservative majority government elected in 2015. By 2018–19, annual spending by government departments had been slashed by around ten per cent, some £41.3 billion in real terms (Emmerson et al. 2019). Total state expenditure had grown 21.5 per cent during the 1990s and 47.6 per cent during the 2000s; during the 2010s it rose a mere 2.2 per cent (see Figure 1). Combined with the economic aftershocks of the 2008 recession, these spending restrictions had a deleterious impact on public health in this period. Across the population, the number of years spent in poor health grew and there was an almost unprecedented slowdown in life expectancy, with many of the most deprived areas experiencing actual declines (Marmot et al. 2020). Suicides and self-reported mental health problems increased, while social and geographical inequalities in mental health widened (Barr et al. 2015, Curtis et al. 2021). Researchers have begun to highlight some of the mechanisms through which the UK austerity programme harmed mental health – most notably, vicious cuts to welfare benefits (Barr et al. 2016, Clifford 2020). However, relatively little attention has been paid to the impacts of austerity upon health services themselves, and how these might be implicated in observed declines in population health. Responding to this oversight, this paper focuses on mental health spending and provision under austerity in England.

Figure 1: UK government spending (Total managed expenditure) in real terms (£ billion) and as a percentage of GDP, 1982–83 to 2022–23. Note. See Appendix II.I for data sources.

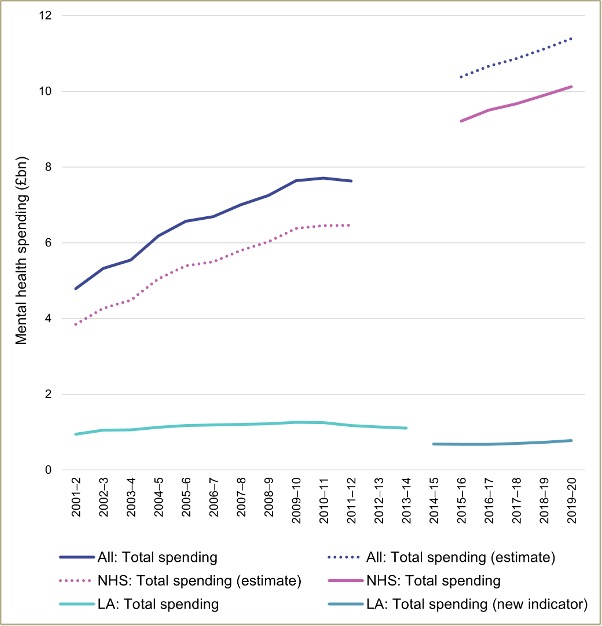

To date, no study has systematically investigated expenditure on and utilisation of mental health services during the austerity years. While a few authors have addressed the topic in passing, their accounts are often simplistic: they tend to suggest that spending was straightforwardly cut across the country. Thus, in a widely cited paper, Cummins (2018, p. 8) states that the ‘damage that nearly a decade of austerity has done to mental health services is apparent […] Services faced increased pressures to do more with less’ (emphasis added). However, Cummins provides no empirical evidence to support this claim of reductions in resources. Meanwhile, Moth (2022, p. 132) describes a ‘funding squeeze’ that has had damaging impacts on mental health services, while noting in passing the introduction of ‘mechanisms that purport to monitor and address underfunding’ (emphasis added) – the implication is that these mechanisms, in practice, do no such thing. Both authors therefore overlook the sizeable increases in mental health spending that have taken place during the austerity years (see Figure 2). These figures suggest that any direct cuts to mental health services have been more than offset by a rise in expenditure during this period.

Figure 2: Spending on adult mental health services in England in real terms, 2001–2 to 2019–20. Note. See Appendix II.II for data sources and methods.

The major contribution of this paper is therefore a comprehensive analysis of the mental health service landscape under austerity in England which accounts for this increase in spending. In addition, the paper advances critical scholarship on austerity and public health, in two ways. First, it argues that there is limited utility in narrating austerity within mental health services in terms of national spending trends. Mental health expenditure is spatially uneven, with wide divergences even in proximate areas. Headline funding increases at the national level thereby conceal localised austerities: cuts to expenditure over successive financial years within single localities. While geographical and temporal variations in mental health expenditure are longstanding (Parsonage 2005), this paper contends that localised austerities are a distinctive phenomenon. These spending reductions take on a newfound significance when state services more broadly are being cut, as this tends to drive demand for universalist healthcare services (Kerasidou & Kingori 2019). This paper therefore demonstrates that the effects of austerity on mental health services are likely to be highly localised, contributing to geographical scholarship which has demonstrated the unevenness of austerity in England (Gray & Barford 2018). The concept of localised austerities highlights the multiple, often contradictory dynamics shaping funding distributions – and therefore public health – in each locality. It acknowledges that increases in expenditure and ongoing austerity can coexist on the same service landscape, without granting analytical priority to either. This draws attention to the reorganisation of the state under austerity, as much as its retrenchment (Seymour 2014).

Second, the paper interrogates the forms of mental health service provision that have emerged under austerity, to explore why national increases in spending have been unable to prevent a sharp deterioration in public mental health during this period. It argues that the English mental health service landscape has seen a redistribution of financing and functions towards the most and least ‘risky’ patients, at the expense of others who fall in between. This is part of a broader restructuring of the state ‘as a less welfarist and more penal and coercive institution’ (Seymour 2014, p. 4). This analysis has two important implications for public health scholarship and practice. First, it highlights the complexity of the political, economic and institutional dynamics which determine where cuts fall, and therefore mediate austerity’s effects on public health. Second, it demonstrates the limitations of increased mental health service spending as both a political demand and policy response in the context of austerity.

Methods

This paper offers a descriptive analysis of mental health spending and provision in the UK from 2009–10 – the year before austerity was inaugurated – until 2019–20, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter arguably marked the end of the current period of fiscal austerity, as from this point real-terms public sector expenditure on services consistently surpassed 2009–10 levels. In this context, a descriptive analysis uses descriptive statistics to provide an overview of trends in the distribution of funding and other resources over time (Wood et al. 2023). The analysis focuses on the two public bodies responsible for mental health expenditure in England. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) were General Practitioner (GP)-led organisations with statutory responsibility for commissioning services within given localities to meet acute and chronic health needs (Hammond et al. 2017). By April 2020 there were 135 of these organisations, which together were responsible for around 85 per cent of National Health Service (NHS) mental health spending (NHS England 2021). Mental health provision funded by these NHS bodies includes psychiatric hospitals and other inpatient services, community services (such as crisis teams, home treatment teams, community mental health teams and Recovery Colleges), and the prescribing of psychiatric medications. While services are commissioned to meet the health needs of populations within a locality, in many cases patients retain the legal right to choose where they travel to receive treatment. Local authorities (LAs) are regional governments that typically oversee one metropolitan or county area. LAs hold statutory responsibility for services that provide social care support with daily living (Thane 2009). This includes a range of preventive, residential and community mental health services (for instance, Crisis Cafés, day centres and employment support services), as well as the distribution of personal budgets for service users to purchase their own care. In practice, many mental health services are delivered through partnership arrangements and other forms of co-commissioning between CCGs and LAs (Moth 2022).

The analysis compares mental health expenditure data for these two public bodies drawn from three sources. Data on NHS mental health spending from 2016–17 to 2019–20 was extracted from NHS mental health dashboards for relevant years at the CCG level (NHS England 2022b). Where relevant, spending totals for CCG areas were pooled to account for mergers during this period. Two CCGs (North Cumbria and Morecambe Bay) were excluded due to boundary changes. CCG-level figures include learning disability and dementia spending, which cannot be disaggregated from the total. Consequently, reductions in spend within some CCGs may reflect cuts to learning disabilities and dementia rather than mental health. In 2019–20, learning disability and dementia spending amounted to £2.17 billion, or some 17 per cent of total projected spend (NHS England 2020). This figure has stayed relatively stable across time but may vary between CCGs. Data on local authority expenditure on mental health from 2003–4 to 2013–14 was extracted from NHS Digital community care statistics (NHS Digital 2014). Equivalent data for 2014–15 to 2019–20 were extracted from NHS Digital adult social care activity and finance reports for relevant years (NHS Digital 2023): details on the indicators selected for these figures can be found in Appendix II.II. Data were converted into real-terms per capita figures in 2019–20 prices and compound annual growth rates were calculated at the CCG and local authority level to compare relative rates of change in expenditure over this period (see Appendix I.I–I.III).

The analysis allows the comparison of variations in mental health expenditure across space and time during the austerity period, adjusted to account for inflation and population change. As NHS mental health spending data was only available from 2016–17, the analysis also utilised a grey literature search to gather data on spending and provision in earlier years. Finally, a range of statistics on inpatient and community mental health services, including those on bed numbers, staffing levels, contacts with services and prescribing levels, were extracted from official NHS and LA datasets, and secondary literature. This allows changes in expenditure to be compared with changes in service provision and utilisation across the austerity period.

Findings

National Mental Health Spending

During the austerity years, the NHS was responsible for the vast majority of mental health expenditure. For example, in 2018–19, NHS spending totalled £10.6 billion while LAs spent £1.2 billion (see Appendix II.II). Little data is available on NHS expenditure during the early years of austerity. However, two pieces of evidence suggest that NHS mental health spending fell in this period. First, a longstanding Department of Health survey measuring NHS and LA mental health investment shows that total spending increased considerably under the previous Labour government, and then fell during the first year of austerity (see Figure 2). The survey was then discontinued (Thornicraft & Docherty 2013). Second, a series of studies in the grey literature have examined the accounts of specialist NHS mental health trusts (Buchanan 2013, Gilburt 2015, 2018, McNicoll 2015, RCPsych 2018), which provide the majority of secondary mental health services. The analyses consistently showed the budgets of mental health trusts falling up to 2016–17 (see Table 1). LA mental health spending in this period evidenced a similar trend: it rose until 2010–11 before decreasing.

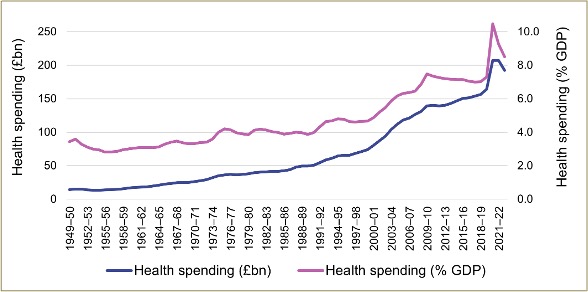

From 2016–17 there was a reversal. NHS mental health expenditure began to rise, increasing on average 2.7 per cent each year in real terms between 2015–16 and 2019–20 (NHS England 2021; see Appendix I.I and I.III). By 2016–17, the number of mental health Trusts reporting a nominal-terms cut had fallen to 16 per cent (Gilburt 2018). A similar trend can be seen in LA expenditure on mental health (albeit measured by a new indicator): spending was flat until 2015–16, and then began to rise again. These increases during the later years of austerity demonstrate that the period cannot be characterised as one of unmitigated retrenchment. Mental health spending therefore followed a similar pattern to overall public expenditure on health (see Figure 3). Health spending stagnated during the early years of austerity (and decreased as a share of GDP), before rising again during the latter half of the decade – although still at a much slower rate than during the 1990s and 2000s.

|

Study |

Organisation |

Trusts studied |

Key findings |

|

Buchanan (2013) |

BBC |

43/51 |

– 2.36% real-terms budget cut from 2011–12 to 2013–14 |

|

Gilburt (2015) |

King’s Fund |

57/57 |

– 44.8% of trusts reported falling incomes in 2013–14 – Decreased to 38.6% of trusts in 2014–15 |

|

McNicoll (2015) |

BBC/Community Care |

43/56 |

– 8.25% real-terms budget cut from 2010–11 to 2014–15 |

|

Gilburt (2018) |

King’s Fund |

55/55 |

– 40% of trusts reported a nominal-terms budget cut in 2014–15 – Increased to 50% in 2015–16 |

|

RCPsych (2018) |

Royal College of Psychiatrists |

55/55 |

– 62% of trusts reported lower income in 2016–17 than in 2011–12 – 5 trusts saw income fall in all 5 years |

Table 1: Grey literature studies of NHS mental health trust accounts.

Figure 3: UK government spending on health in real terms (£ billion) and as a percentage of GDP, 1949–50 to 2022–23. Note. See Appendix II.III for data sources and methods.

Regional and Local Mental Health Spending

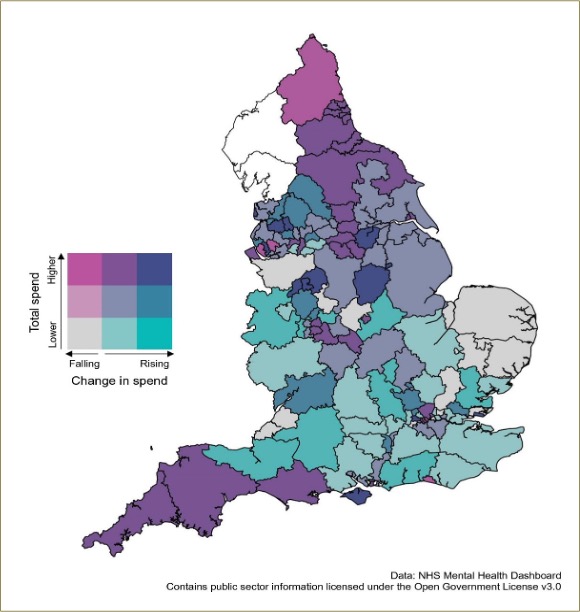

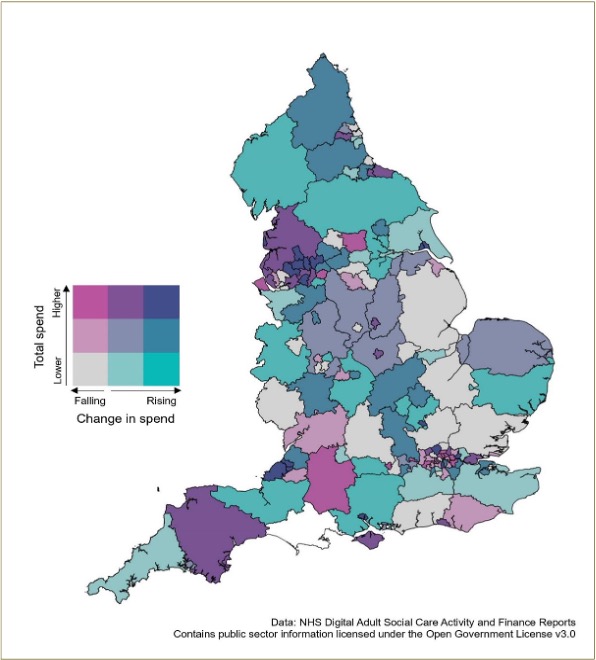

Even as national spending rose from 2016–17 onwards, there remain significant geographical inequalities in NHS mental health expenditure between localities. In 2019–20, the outlay of the highest-spending CCG (West London) was almost three times higher per capita than the lowest (Oxfordshire). Across the country, higher expenditure was generally concentrated in more urban and more deprived areas (see Figure A1 in Appendix II). Figure 4 shows the diversity of mental health spending patterns by classifying CCGs into nine categories, based on two rankings: overall per capita spending in 2019–20 (low, medium or high), and change in real-terms per capita spending from 2016–17 to 2019–20 (falling, slight increase or high increase). In this period, 18 out of 135 CCGs (13.3 per cent) cut mental health spending: five by more than three per cent each year. These localised austerities (marked light grey and dark pink on the map) are concentrated in East Anglia, North West England and London. The areas they affect are divergent, both in terms of their mental health spending (either high or low) and deprivation levels (see Figure A2 in Appendix II). Such contextual factors are likely to shape the impacts of spending cuts, further demonstrating that austerity in mental health service provision is highly localised.

Figure 4: Bivariate map of total spend per capita, 2019–20, and annual percentage change in real-terms spend per capita, 2016–17 to 2019–20, on mental health by Clinical Commissioning Groups in England. Note. See Appendix II.IV for data sources and methods.

Figure 5: Bivariate map of total spend per capita, 2019–20 (£), and annual percentage change in real-terms spend per capita, 2016–17 to 2019–20, on long- and short-term mental health support for adults aged 18–64 by local authorities in England. Note. See Appendix II.V for data sources and methods.

There are similar inequalities within LA mental health expenditure. During 2019–20, Liverpool spent almost 14 times more than Lincolnshire on mental health support. Overall, deprived urban areas tended to demonstrate the highest levels of spend (see Figure A4 in Appendix II). Figure 5 shows LA areas classified into the same nine categories as in Figure 4. In 2019–20, 56 out of 146 LAs (38.4 per cent) spent less per capita than in 2014–15 (although fluctuations in payment schedules may account for some cuts, see Appendix II.V). The depth of cuts ranged from 16 per cent to 0.08 per cent, with a median of five per cent. Localised austerities (marked light grey, light pink and dark pink) were predominantly concentrated in London, the South East and the Midlands, again in areas with various underlying levels of mental health spending and deprivation (see Figure A5 in Appendix II). These cuts reflect a decline in LA spending power due to large reductions in annual government grants since 2009–10: these were 77 per cent lower per capita by 2019–20. By that year, LAs were spending seven per cent less on adult social care per capita than a decade previously – as this expenditure is protected by statute – and 40 per cent less on all other areas of non-statutory spending (Phillips et al. 2019). With non-grant revenue largely derived from local business and property taxes, LAs in poorer areas have lower capacities to generate income (Gray & Barford 2018), so cuts to net service spending were almost twice as deep in the most deprived LAs (Phillips et al. 2019). Different localities also chose different mixes of services to cut versus protect (Gray & Barford 2018), likely with distinctive knock-on effects for mental health services. Again, this highlights the significance of local context, and therefore the localisation of austerity.

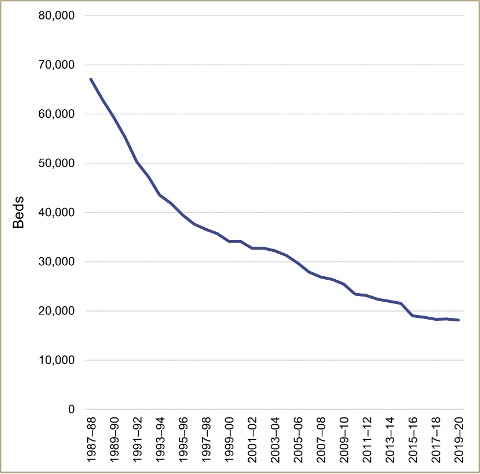

Figure 6: Number of NHS Mental Illness beds in England, 1987–88 to 2019–20. Note. Data from NHS England (2022a)

Inpatient Mental Health Service Provision

If austerity’s impacts are spatially uneven, then how might they be playing out in different areas of the mental health service landscape? Inpatient services in this period have been characterised by two trends: declining capacity and increasing coercion. While only 1.8 per cent of adults diagnosed with ‘severe mental health disorders’ go on to receive inpatient treatment (Degli Esposti et al. 2021), these services account for a considerable proportion of mental health expenditure. For instance, 15 per cent of NHS mental health expenditure in 2019–20 was directed to ‘specialist commissioning’, for the most intensive inpatient services (NHS England 2020). Under austerity, both staffing and provision have fallen across inpatient settings, furthering a trend that began with the mass closures of asylums in the 1990s (Parr 2008, see Figure 6). Between 2010–11 and 2019–20, bed numbers fell 22.5 per cent, while average bed occupancy rates were 88.7 per cent (NHS England 2022a), against a recommended safe maximum of 85 per cent (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2021). Meanwhile, from 2009 to 2019 the number of mental health nurses in inpatient settings declined by almost 6,200, more than 24 per cent, though the number of nurses in community settings rose by over 2,800 (see Figure A8 in Appendix II).

Against this backdrop, inpatient services have also become more coercive. Rates of ‘sectioning’ – the involuntary detention of patients under the Mental Health Act (MHA) – have more than doubled since 1983. Between 2008 and 2017 the rise in detention rates was one of the sharpest in Europe (Sheridan Rains et al. 2019). Within psychiatric hospitals, recently released statistics also show a large rise in uses of restraint, although these figures remain too unreliable to track actual rates of change. There were 80,387 instances of ‘restrictive intervention’ – including physical, chemical and mechanical restraints, plus uses of seclusion – in 2016–17, rising to 131,338 instances during 2019–20. This is equivalent to around one intervention per 45 bed days, between 1.8 and 4.5 times higher than historical estimates of restraint rates (see Appendix II.VI). In 2016–17, more than 3,600 inpatients were injured through restraint (Campbell 2018), a threefold increase since 2011–12 (Mind 2013). Between 2011 and 2014, 41 patients detained under the MHA were killed while being restrained (IAPDC, 2015). Data on these deaths are no longer being collected.

Police involvement in the mental health system has also increased. The Metropolitan Police (the largest force in the country, responsible for Greater London) estimated that between 20 and 40 per cent of police time is spent on incidents relating to mental health (ICMHP 2013). Uses of section 136 of the MHA – which allow police officers to detain people suspected of ‘mental disorder’ – more than doubled between 2001–02 and 2006–07 to reach 6,000 per year (Department of Health 2014). By 2019–20, this figure had more than tripled to 18,665 uses per year (NHS Digital 2020b). There is also evidence of police coercion being deployed within inpatient units, although again these figures remain unreliable. In 2019–20, newly released use of force statistics recorded 4,932 ‘incidents’ involving police in mental health settings, with listed ‘tactics’ including handcuffing, ‘unarmed skills’ (arm and leg locks, punches and kicks), and the use of tasers and pepper sprays (Home Office 2021).

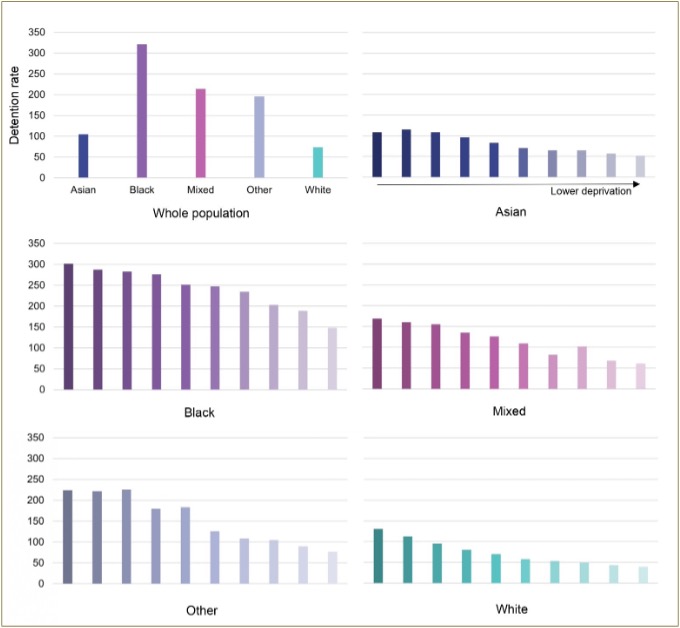

The distribution of these coercive practices is shaped by race, gender and class. In 2019–20, people from all other ethnic groups were more likely to be sectioned than white people, while within each ethnic group people from more deprived areas were sectioned more often (see Figure 7). Women were subjected to 54 per cent more restraints than men, despite making up a smaller proportion of the inpatient population, while men were more likely to be sectioned (NHS Digital 2020c, 2020b). Compared to white people, Black people were four times more likely to be restrained on mental health wards, four times more likely to be sectioned and – across all settings, including mental health institutions – disproportionately likely to experience a use of force by the police (NHS Digital 2020c, 2020b, Home Office 2021).

Community Mental Health Service Provision

Under austerity, community mental health services have seen a shift towards time-limited provision within the NHS, and a major decline in the number of people receiving care from LAs. Against this backdrop, onerous new conditionalities have been added to the welfare benefits that many patients rely on to survive. There is also evidence that mental health services have become increasingly inaccessible, with patients struggling to secure the care that they need. This highlights two further trends that are characterising the mental health service landscape in this period: conditionalisation and abandonment.

Figure 7: Rates of detention under the Mental Health Act 1983 in England per 100,000, by ethnicity and deprivation decile, 2019–20. Note. See Appendix II.VII for data sources and methods.

Within the NHS, there has been a major expansion in the number of people treated through the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme. Since 2011–12, IAPT has offered time-limited courses of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for ‘mild’ anxiety and depression (Pickersgill 2019). In 2019–20, 1.2 million people were receiving treatment (NHS Digital 2020d), more than double the number referred at the start of the decade (Stanton et al. 2015). IAPT accounted for 7.2 per cent of CCG adult mental health spend in 2019–20, up from six per cent in 2017–18 (NHS England 2018, 2020).

In contrast, LA community services have seen sharp falls in the number of attendances. Between 2006–7 and 2009–10, the number of people attending LA-funded mental health services grew 5.7 per cent. By 2013–14, this had fallen by 26.5 per cent (see Figure 8). LAs attributed these declines to data cleaning, increasing eligibility thresholds and service closures (NHS Digital 2012). To some extent, they therefore reflect people losing access to services (Kiely & Warnock 2023). During this period, LAs were transferring service users to personal budgets, direct payments and other forms of self directed support as part of a transition to more personalised forms of social care (Tarrant 2020). However, the rise of personalisation does not account for the declines in attendances at services. Between 2009–10 and 2013–14, only 23,685 people gained access to self directed support while 69,675 people left LA mental health services – a net loss of 45,990 people. Between 2014–15 and 2019–20, there was a further net loss of 7,485 people.

Figure 8. Number of people receiving commissioned services and self directed support (including direct payments) from local authorities in England, 2006–7 to 2019–20. Note. See Appendix II.VIII for data sources and methods.

Access to care has also seemingly worsened under austerity. While there is no official data on mental health waiting times, survey data suggests that patients are waiting longer (Anandaciva et al. 2018). One large survey found average waits of 14 weeks for assessment, and a further 19 weeks for treatment. However, 9.4 per cent of respondents had waited six months or more for assessment, and 16 per cent had waited six months or more for treatment (Rethink, 2018). Simultaneously, patients have become more likely to seek emergency mental health care, with Accident and Emergnency (A&E) attendances for psychiatric conditions increasing 71 per cent between 2015–16 and 2019–20 (NHS Digital 2017, 2020a). Meanwhile, it is estimated that between 30 and 50 per cent of people diagnosed with ‘serious and enduring mental health conditions’ receive support only from their GP, without specialist input (Naylor et al. 2020). Mental health patients have also been impacted by cuts to welfare benefits under austerity. Claimants of the Employment and Support Allowance and the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) have been forced to undergo mandatory reassessments, to classify them as fit or unfit to work (Clifford 2020). For PIP claimants diagnosed with mental health conditions, 37.9 per cent of reassessments to date have ended with the removal of all benefits. A further 17 per cent ended with a decreased award. In total, at least 211,729 claimants with mental health diagnoses have lost income through these reassessments (see Appendix II.IX).

Discussion

It is challenging to assess the financial impact of austerity on mental health services due to a lack of comprehensive data. Evidence of cuts to spending up to 2016–17 is piecemeal and inconclusive. For instance, declines in mental health trust accounts in this period could reflect funds being passed instead to other non-NHS providers – though the proportion of NHS mental health spend absorbed by these trusts seemed to remain relatively constant (Gilburt 2015). Most significantly, the decommissioning of the Department of Health National Survey of Investment in Adult Mental Health Services in 2012 ended the only national-level time series tracking mental health spending (Thornicraft & Docherty 2013); changes to LA spending statistics in 2014–15 also broke long-running time series. The loss of this data contributes to what Tyler (2020, p. 173) describes as an ‘unseeing’ of austerity, an erasure that prevents an adequate reckoning with its consequences. Whatever the cause of these changes to data collection, they are politically convenient for those who back austerity – and UK governments have long been criticised for decommissioning statistics which demonstrate the damage done by their policies (Radical Statistics Group 1998, Römer 2022).

While mental health spending is likely to have fallen in the early years of austerity, later rises in mental health spending seem to have been greater in magnitude: significant enough to return national-level expenditure to its pre-2010 trend. The policy mechanism which drove these increases was the Mental Health Investment Standard (MHIS), which required each CCG to ‘increase investment in mental health services in line with their overall increase in allocation each year’ (Mental Health Taskforce 2016, p. 66). Introduced from 2016, the MHIS operationalised a promise made in the early years of the Coalition government to achieve ‘parity of esteem between mental and physical health services’ (HM Government 2011, p. 64). Under the subsequent Conservative government led by Theresa May, mental health was identified as a ‘burning injustice’ (May 2017) and therefore prioritised for economic support. May’s framing of mental health in terms of justice should be seen as part of a broader discourse which divided the deserving from the undeserving poor – typically along racial lines – in order to justify the austerity project, with certain marginalised groups (notably disabled people and ‘foreign criminals’) targeted for disciplining by the state (Bhattacharyya et al. 2021, Clifford 2020, Shilliam 2018). The MHIS – accompanied by an injection of £2.85 billion of additional funding (HFMA 2017) – can therefore be read as a highly publicised financial boost to a constituency hailed as deserving.

In practice, the MHIS remains a relatively weak policy instrument, tying mental health expenditure to overall health funding. Given the anaemic growth in health spending across the decade, it is unsurprising that this was insufficient to drive austerity from mental health services. Instead, when taking inflation and population into account, localised austerities continued in many places. The uneven local impacts of national spending policies highlighted by this paper have two crucial implications for public health scholars and practitioners. First, it highlights that austerity can produce divergences within different parts of the healthcare system. For instance, NHS and LA mental health spending is highest in in deprived urban areas, reflecting well-established epidemiological relationships between poverty, urban living and distress (Fitzgerald et al. 2016). Mental health spending cuts are seemingly independent of these factors, while cuts to overall social care services are largest in deprived areas. Second, and relatedly, it suggests that these dynamics can pull in different directions even within the same local area. Consequently, austerity’s impacts on health systems and populations should be theorised as the outcome of multiple intersecting yet divergent trends within localities – a complexity to which public health interventions must respond.

Beyond localisation, this study suggests that the mental health service landscape under austerity is shaped by three further trends. First, inpatient services have become increasingly coercive. While data quality remains poor, the available evidence suggests that both sectioning and the use of ‘restrictive interventions’ has increased under austerity. Indeed, the lack of data demonstrates the relative impunity with which these practices have historically been treated. It is clear that carceral mental health services remain a spending priority, reflecting an ongoing concern among policymakers with the risk that ‘dangerous’ psychiatric patients pose to the public (N. Rose 1996). Simultaneously, the long transition away from asylum care (Parr 2008) – which materialises in declining bed numbers and staffing levels – is placing this part of the mental health system under significant strain. Austerity is a potential cause of both understaffing (by depressing wages) and overcrowding (by incentivising the closure of beds). In turn, it is plausible that these trends could be driving increases in coercion, though further research is needed (Busch & Shore 2000, Sheridan Rains et al. 2020). For instance, service shortfalls could lead to patients’ conditions worsening, leading to more detentions. Overcrowding could increase stress among staff and patients, driving rates of violence. Evidence also suggests that services are responding to these pressures by involving the police, a major concern given that police officers have killed multiple patients while detaining them, including on mental health wards (Bruce-Jones 2021). Police are also being used to reduce demands on provision. In recent years, almost half of NHS mental health trusts have deployed police officers to discourage ‘high frequency’ patients from contacting services, through threats of legal sanctions. This secretive practice was exposed by a campaign led by service user/survivor activists (see StopSIM 2021). Cuts to services in one area can therefore lead to greater demand in another, hampering state retrenchment. Moreover, this can spur coercive practices, which – as detention statistics demonstrate – are unevenly distributed along axes of race and class. Public health scholars and practitioners must take these iatrogenic harms seriously, as service users/survivors have long argued (Black Health Workers and Patients Group 1983, Sweeney et al. 2015), while their interaction with race, class and other structures of marginalisation demands an intersectional approach (Thompson 2021).

Second, the conditionalisation of community mental health services has also progressed during this period. Conditionalisation of state welfare has long been identified as one of the hallmarks of austerity (Kiely 2024). In the context of mental health provision, this process has become entangled with the rollout of a recovery model that prioritises individual resilience over collective support (Harper & Speed 2012). Service user/survivor critics have highlighted the replacement of open-ended provision with recovery oriented services that are short-term and employment-focussed (Recovery in the Bin et al. 2019; D. Rose 2014). The emergence of IAPT services – designed to lower costs per patient while improving measurable recovery rates (Pickersgill 2019) – should be seen as part of this process. IAPT sees resources reserved for those who can return to the labour market, as those who are more unwell can be automatically discharged (Kiely 2021). Consequently, the mental health services which have expanded the most under austerity offer short-term treatments to those diagnosed with the ‘mildest’ conditions, supporting a range of welfare conditionalities that motivate employment.

This leads to the third trend shaping the austere mental health service landscape: the abandonment of many who are experiencing severe distress, yet unable to access services. The decline in attendances at local authority services implies that open-ended, accessible forms of provision are being lost (Kiely 2024), while the increase in A&E attendances for mental health suggests a more pervasive lack of access to care. The growth of IAPT means that this gap is most likely to affect those whose conditions are serious and enduring, but who are not judged ‘risky’ enough to warrant inpatient treatment. Social abandonment is often contradictory, defined by a dynamic in which people are excluded from welfare institutions, which nonetheless continue to shape their lives (Biehl 2005). This contradictory dynamic can be seen within mental health services, where discharge is leveraged as a threat to ensure compliance (Kiely & Warnock 2023), but where services must remain accountable for a patient’s risk (N. Rose 1996). In practice, this means that abandonment describes not only the condition of losing all contact with services. It can also refer to patients receiving care only from a GP, but where more specialist support is warranted. And it refers to cases where patients are bounced back and forth between mental health services – too ill for one, not ill enough for another – through durative cycles of referral and re-referral (Kiely 2021). In conditions of abandonment, care remains perpetually deferred. This dynamic creates a pressing challenge for critical public health: how to design and provide services that support this abandoned middle, at a time of significant resource constraint, without relying on a business case predicated on an eventual return to employment.

Conclusion

The complex geographies of austerity within the English mental health system have been largely elided by prior accounts. This paper offers a descriptive analysis of these geographies, drawing on a comprehensive set of statistics and indicators. It argues that headline increases in funding for mental health conceal a fragmented spending landscape, with real-terms per capita cuts continuing in many areas. While uneven distributions of expenditure are longstanding, this paper argues that they take on a newfound significance against the backdrop of broader attempts to shrink the (welfare) state. In this context, consistent cuts to spending within smaller geographical areas should be conceptualised as localised austerities. These cuts are likely to prove particularly harmful when large swathes of the public sector are under strain from years of fiscal constraint. Yet the wide divergences within localised spending uncovered by this study also demonstrate the capacity of some places to protect expenditure, at least for certain forms of provision. This draws attention to the complex trade-offs facing local policymakers under austerity. It also highlights the limited utility of conceiving economic policies at only the national scale. A crucial question for future public health scholarship is if and how these variations between localities might be determining public mental health.

The complexity of these geographies was only increased by the COVID-19 pandemic. The resultant fiscal stimulus ended a decade of flat real-terms spending growth. Yet outside of short-term emergency funding, the core resource budgets of most Whitehall departments remained lower than in 2009–10 (Zaranko 2021). And with inflation rampant, spending uplifts turned into real-terms cuts (Zaranko 2022). Among LAs, the crisis prompted a rapid increase in spending – not least to fund places for those discharged from hospitals into care homes, with tragic results (Morciano et al. 2021) – as commercial revenue streams collapsed. While central government announced additional grants, there were insufficient to cover the deficit (Ogden et al. 2021). A huge rise in national funding therefore continued to mask myriad localised austerities.

The pandemic also reveals that the central dynamics identified within this paper – coercion and abandonment – are continuing to shape mental health services in England. Multiple waves of COVID-19 swept across psychiatric wards, killing at least 176 patients held under section; the true number of deaths is almost certainly much higher (see Appendix II.X). Sectioning rates increased (NHS Digital 2021), while the Coronavirus Act 2020 introduced emergency protocols – fortunately never enacted – to make sectioning easier. Meanwhile, lockdowns led to closures of many community services. Their digital replacements were often inadequate, with many patients losing access to provision (Gillard et al. 2021). Coercion, conditionalisation and abandonment preceded austerity and COVID-19, yet it is possible that they are becoming the default responses to increasing demand and delimited resources within the mental health system. The parlous state of UK public finances, combined with the tendency of political elites to promise austerity in response to market turmoil, may well tie the hands of public health practitioners who wish to unpick these inequities.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the two anonymous reviewers and to editor Lindsay McLaren for comprehensive and constructive feedback which greatly improved this paper.

Funding

The research and writing of this paper was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/J500033/1] and a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellowship [grant number ECF-2023-345].

References

Anandaciva, S., Jabbal, J., Maguire, D., Ward, D., & Gilburt, H. (2018, December 21). How is the NHS performing? December 2018 quarterly monitoring report. The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/how-nhs-performing-december-2018 (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Barr, B., Kinderman, P., & Whitehead, M. (2015) Trends in mental health inequalities in England during a period of recession, austerity and welfare reform 2004 to 2013. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.009

Barr, B., Taylor-Robinson, D., Stuckler, D., Loopstra, R., Reeves, A., & Whitehead, M. (2016) ‘First, do no harm’: Are disability assessments associated with adverse trends in mental health? A longitudinal ecological study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(4), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206209

Bhattacharyya, G., Elliot-Cooper, A., Balani, S., Nişancıoğlu, K., Koram, K., Gebrial, D., El-Enany, N., & de Noronha, L. (2021) Empire’s Endgame: Racism and the British state. Pluto Press.

Biehl, J. G. (2005) Vita: Life in a zone of social abandonment (1st ed.). University of California Press.

Black Health Workers and Patients Group (1983) Psychiatry and the corporate state. Race & Class, 25(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639688302500205

Blyth, M. (2013) Austerity: The history of a dangerous idea. Oxford University Press.

Bruce-Jones, E. (2021) Mental health and death in custody: The Angiolini Review. Race & Class, 62(3), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396820968033

Buchanan, M. (2013, December 12) Funds cut for mental health trusts in England. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-25331644 (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Busch, A. B., & Shore, M. F. (2000) Seclusion and restraint: A review of recent literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8(5), 261–270.

Campbell, D. (2018, June 9) Figures reveal ‘alarming’ rise in injuries at mental health units. The Observer. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jun/09/nhs-restraint-techniques-mental-heath-patient-injuries-rise (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Clifford, E. (2020) The War on Disabled People: Capitalism, welfare and the making of a human catastrophe. Zed Books.

Cummins, I. (2018) The impact of austerity on mental health service provision: A UK perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061145

Curtis, S., Cunningham, N., Pearce, J., Congdon, P., Cherrie, M., & Atkinson, S. (2021) Trajectories in mental health and socio-spatial conditions in a time of economic recovery and austerity: A longitudinal study in England 2011–17. Social Science & Medicine, 270, 113654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113654

Degli Esposti, M., Ziauddeen, H., Bowes, L., Reeves, A., Chekroud, A. M., Humphreys, D. K., & Ford, T. (2021) Trends in inpatient care for psychiatric disorders in NHS hospitals across England, 1998/99–2019/20: An observational time series analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02215-5

Department of Health (2014) Review of the Operation of Sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983: Review Report and Recommendations. Department of Health/Home Office. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7d5b6740f0b60a7f1aa05b/S135_and_S136_of_the_Mental_Health_Act_-_full_outcome.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Emmerson, C., Pope, T., & Zaranko, B. (2019) The outlook for the 2019 Spending Review. The Institute for Fiscal Studies. https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/BN243.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Fitzgerald, D., Rose, N., & Singh, I. (2016) Revitalizing sociology: Urban life and mental illness between history and the present. The British Journal of Sociology, 67(1), 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12188

Gilburt, H. (2015) Mental health under pressure. The King’s Fund. https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/78db101b90/mental_health_under_pressure_2015.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Gilburt, H. (2018) Funding and staffing of NHS mental health providers: Still waiting for parity. The King’s Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/funding-staffing-mental-health-providers (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Gillard, S., Dare, C., Hardy, J., Nyikavaranda, P., Rowan Olive, R., Shah, P., … NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit Covid Coproduction Research Group. (2021) Experiences of living with mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: A coproduced, participatory qualitative interview study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(8), 1447–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02051-7

Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018) The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

Hammond, J., Lorne, C., Coleman, A., Allen, P., Mays, N., Dam, R., Mason, T., & Checkland, K. (2017) The spatial politics of place and health policy: Exploring Sustainability and Transformation Plans in the English NHS. Social Science & Medicine, 190, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.007

Harper, D., & Speed, E. (2012) Uncovering recovery: The resistible rise of recovery and resilience. Studies in Social Justice, 6(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137304667_3

HFMA (2017) Mental health investment standard. Healthcare Financial Management Association. https://web.archive.org/web/20220429101621/https://www.hfma.org.uk/docs/default-source/our-networks/faculties/mh-finance-faculty-information/mh-finance-faculty/mental-health-investment-service-2017 (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

HM Government (2011) No Health without Mental Health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. Department of Health. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/138253/dh_124058.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Home Office (2021) Police use of force statistics, England and Wales: April 2019 to March 2020: Data tables. Home Office. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/944989/police-use-of-force-apr2019-mar2020-hosb3720-tables.ods (Accessed 12/02/24)

IAPDC (2015) Deaths in State Custody: An examination of the cases 2000 to 2014. Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c5ae65ed86cc93b6c1e19a3/t/605b13e774179f7f664950d3/1616581608638/IAP+Statistical+Release+2014.pdf (Accessed 12/02/24)

ICMHP (2013) Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing Report. Independent Commission on Mental Health and Policing. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/10_05_13_report.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Kerasidou, A., & Kingori, P. (2019) Austerity measures and the transforming role of A&E professionals in a weakening welfare system. PLoS ONE, 14(2), e0212314. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212314

Kiely, E. (2021) Stasis disguised as motion: Waiting, endurance and the camouflaging of austerity in mental health services. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(3), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12431

Kiely, E. (2024) Entrepreneurship as conditionality: New geographies of work(fare) in mental health services under austerity. Geoforum, 150, 103996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2024.103996

Kiely, E., & Warnock, R. (2023) The banality of state violence: Institutional neglect in austere local authorities. Critical Social Policy, 43(2), 316–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183221104976

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Boyce, T., Goldblatt, P., & Morrison, J. (2020) Health equity in England: The Marmot review 10 years on. British Medical Journal, m693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m693

May, T. (2017) The shared society: Prime Minister’s speech at the Charity Commission annual meeting. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-shared-society-prime-ministers-speech-at-the-charity-commission-annual-meeting (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

McNicoll, A. (2015, March 20) Mental health trust funding down 8% from 2010 despite coalition’s drive for parity of esteem. Community Care. https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/03/20/mental-health-trust-funding-8-since-2010-despite-coalitions-drive-parity-esteem/ (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Mental Health Taskforce (2016) The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health (p. 82). NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Mental-Health-Taskforce-FYFV-final.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Mind (2013) Mental health crisis care: Physical restraint in crisis. A report on physical restraint in hospital settings in England. Mind. https://www.mind.org.uk/media-a/4378/physical_restraint_final_web_version.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Morciano, M., Stokes, J., Kontopantelis, E., Hall, I., & Turner, A. J. (2021) Excess mortality for care home residents during the first 23 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in England: A national cohort study. BMC Medicine, 19(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-01945-2

Moth, R. (2022) Understanding Mental Distress: Knowledge, Practice and Neoliberal Reform in Community Mental Health Services. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.46692/9781447349884

Naylor, C., Bell, A., Baird, B., Heller, A., & Gilburt, H. (2020) Mental health and primary care networks: Understanding the opportunities. The King’s Fund / Centre for Mental Health. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-07/Mental%20Health%20and%20PCNs%20online%20version_1.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2012) Community Care Statistics, Social Services Activity, England—2010-11, Final release. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-social-care-activity-and-finance-report/community-care-statistics-social-services-activity-england-2010-11-final-release (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2014) Community Care Statistics, Social Services Activity, England—2013-14, Final release: Annex M - Compendium 2000-01 to 2013-14. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub16xxx/pub16133/comm-care-stat-act-eng-2013-14-fin-anxm.xls (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2017) Hospital Accident and Emergency Activity, 2016-17: Tables. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publication/e/7/acci-emer-atte-eng-2016-17-data.xlsx (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2020a) Hospital Accident and Emergency Activity, 2019-20: Tables. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/1A/4A65BF/AE1920_National_Data_Tables%20v1.1.xlsx (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2020b) Mental Health Act Statistics, Annual Figures 2019-20: Data Tables. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/30/622CF2/ment-heal-act-stat-eng-2019-20-data-tab.xlsx (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2020c) Mental Health Bulletin: 2019-20 Reference Tables. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/C6/B88CCE/MHB-1920-ReferenceTables%20v2.xlsx (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2020d) Psychological Therapies: Annual report on the use of IAPT services, England 2019-20. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/B8/F973E1/psych-ther-2019-20-ann-rep.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS Digital (2021) Mental Health Bulletin: 2020-21 Reference Tables. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-bulletin/2020-21-annual-report (Accessed 11 June 2024)

NHS Digital (2023) Adult Social Care Activity and Finance Report. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-social-care-activity-and-finance-report (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS England (2018) Mental Health Five Year Forward View Dashboard Q4 2017/18. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/mhfyfv-dashboard-q4-1718_Final_UPDATED20190716.xlsm (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS England (2020) NHS Mental Health Dashboard Q4 2019/20. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/nhsmh-dashboard-Q4-1920_Republication-May-21-Final.xlsm (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS England (2021) NHS Mental Health Dashboard Q4 2020/21. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/nhsmh-dashboard-Q4-2021_17.5.21_republished-11.11.2021.xlsm (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS England (2022a) Beds Time-series 2010-11 onwards (Bed Availability and Occupancy Data – Overnight). NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/02/Beds-Timeseries-2010-11-onwards-Q3-2021-22-QAZSD.xls (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

NHS England (2022b) NHS England » NHS mental health dashboard. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-mental-health-dashboard/ (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Ogden, K., Phillips, D., & Siôn, C. (2021) 7. What’s happened and what’s next for councils? (p. 51) [IFS Green Budget 2021]. IFS. https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/7-What%2525E2%252580%252599s-happened-and-what%2525E2%252580%252599s-next-for-councils-.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2024)

Parr, H. (2008) Mental Health and Social Space: Towards inclusionary geographies? Blackwell.

Parsonage, M. (2005) The Mental Health Economy. In A. Bell & P. Lindley (Eds.), Beyond the Water Towers: The Unfinished Revolution in Mental Health Services 1985–2005 (pp. 63–72). The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health.

Phillips, D., Hodge, L., & Harris, T. (2019) English local government funding: Trends and challenges in 2019 and beyond. The IFS. https://doi.org/10.1920/re.ifs.2019.0166

Pickersgill, M. (2019) Access, accountability, and the proliferation of psychological therapy: On the introduction of the IAPT initiative and the transformation of mental healthcare. Social Studies of Science, 030631271983407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312719834070

Radical Statistics Group. (1998) Response to ‘Statistics: A Matter of Trust’. Radical Statistics, 69. https://www.radstats.org.uk/no069/response1.htm

RCPsych. (2018) Mental health trusts’ income lower than in 2011-12. Royal College of Psychiatrists. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2018/02/21/mental-health-trusts-income-lower-than-in-2011-12 (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Recovery in the Bin, Edwards, B. M., Burgess, R., & Thomas, E. (2019) Neorecovery: A survivor led conceptualisation and critique. 25th International Mental Health Nursing Research Conference, London. https://recoveryinthebin.org/2019/09/16/ (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Rethink (2018) Right treatment, right time. Rethink Mental Illness. https://www.rethink.org/media/2498/right-treatment-right-place-report.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Römer, F. (2022) Poverty, inequality statistics and knowledge politics under Thatcher. The English Historical Review, 137(585), 513–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceac059

Rose, D. (2014) The mainstreaming of recovery. Journal of Mental Health, 23(5), 217–218. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.928406

Rose, N. (1996) Psychiatry as a political science: Advanced liberalism and the administration of risk. History of the Human Sciences, 9(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/095269519600900201

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2021) Bed occupancy across mental health trusts. Mental Health Watch. https://mentalhealthwatch.rcpsych.ac.uk/indicators/bed-occupancy-across-mental-health-trust (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Seymour, R. (2014). Against Austerity: How we can fix the crisis they made. Pluto Press.

Sheridan Rains, L., Weich, S., Maddock, C., Smith, S., Keown, P., Crepaz-Keay, D., Singh, S. P., Jones, R., Kirkbride, J., Millett, L., Lyons, N., Branthonne-Foster, S., Johnson, S., & Lloyd-Evans, B. (2020) Understanding increasing rates of psychiatric hospital detentions in England: Development and preliminary testing of an explanatory model. BJPsych Open, 6(5), e88. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.64

Sheridan Rains, L., Zenina, T., Dias, M. C., Jones, R., Jeffreys, S., Branthonne-Foster, S., Lloyd-Evans, B., & Johnson, S. (2019) Variations in patterns of involuntary hospitalisation and in legal frameworks: An international comparative study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30090-2

Shilliam, R. (2018) Race and the Undeserving Poor: From abolition to Brexit. Agenda Publishing.

Stanton, E., Wheelan, B., & Surendranathan, T. (2015, February 4) Have we improved access to mental health services? Health Service Journal. https://www.hsj.co.uk/have-we-improved-access-to-mental-health-services/5053577.article (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

StopSIM. (2021) StopSIM. STOPSIM. https://stopsim.co.uk/ (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Sweeney, A., Gillard, S., Wykes, T., & Rose, D. (2015) The role of fear in mental health service users’ experiences: A qualitative exploration. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(7), 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1028-z

Tarrant, A. (2020) Personal budgets in adult social care: The fact and the fiction of the Care Act 2014. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 42(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2020.1796224

Thane, P. (2009) Memorandum submitted to the House of Commons’ Health Committee Inquiry: Social Care. History & Policy. https://www.historyandpolicy.org/docs/thane_social_care.pdf (Accessed 23 Sep 2024)

Thompson, V. E. (2021) Policing in Europe: Disability justice and abolitionist intersectional care. Race & Class, 62(3), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396820966463

Thornicraft, G., & Docherty, M. (2013) Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2013 Public Mental Health Priorities: Investing in the Evidence (D. Sally, Ed.; pp. 197–212). Department of Health. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413196/CMO_web_doc.pdf (Accessed 12 Feb 2024)

Tyler, I. (2020) Stigma: The machinery of inequality. Zed Books.

Wood, B., McCoy, D., Baker, P., Williams, O., & Sacks, G. (2023) The double burden of maldistribution: A descriptive analysis of corporate wealth and income distribution in four unhealthy commodity industries. Critical Public Health, 33(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.2019681

Zaranko, B. (2021) Spending Review 2021: Plans, promises and predicaments (Chapter 5; IFS Green Budget 2021, p. 49). IFS. https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/5-Spending-Review-2021-plans-promises-and-predicaments-.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2024)

Zaranko, B. (2022, August 10) The inflation squeeze on public services. The IFS. https://ifs.org.uk/publications/16145 (Accessed 11 June 2024)

Journal of Critical Public Health, Volume 1 (2024), Issue 2 CC-BY-NC-ND